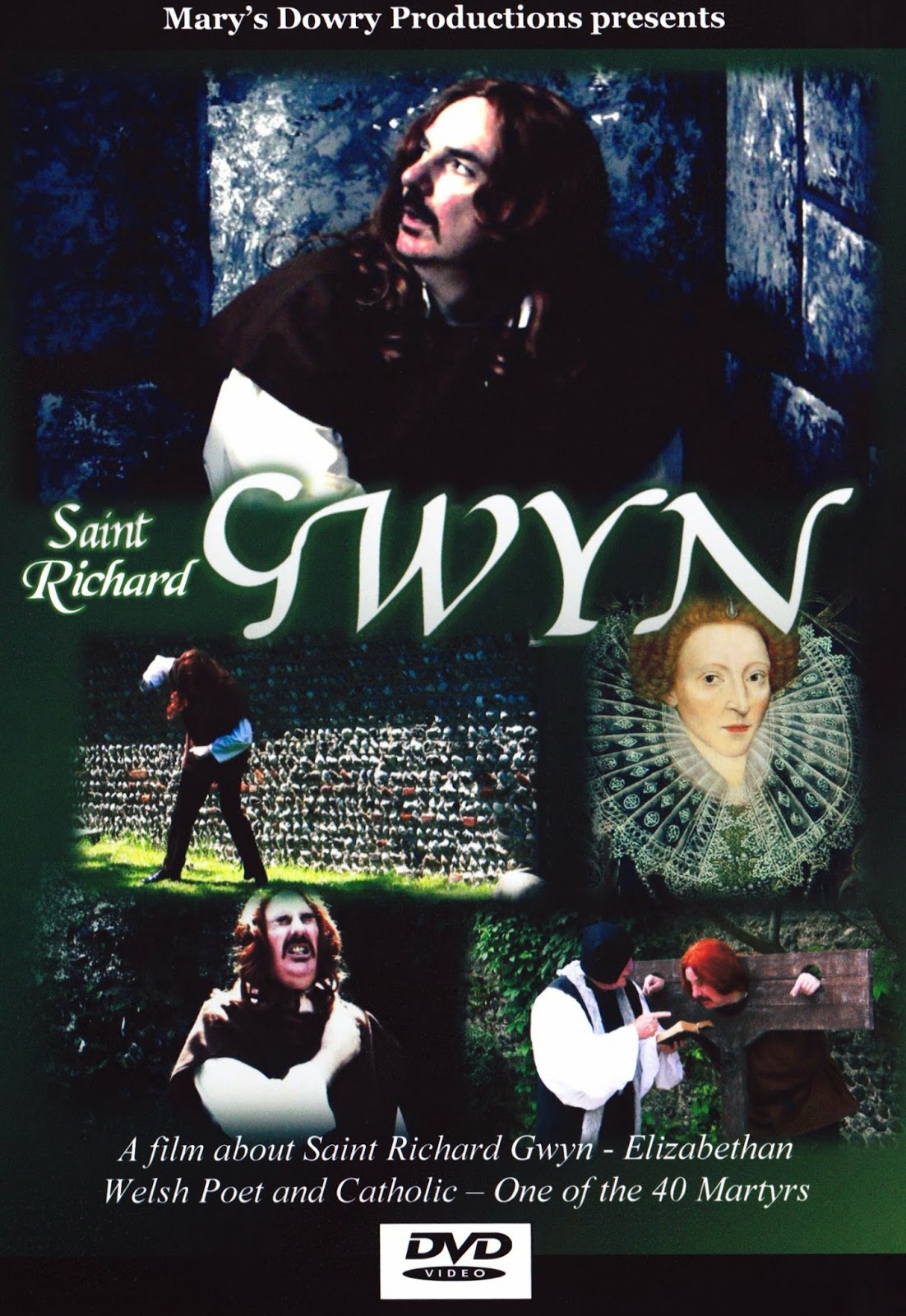

Richard Gwyn (anglicized “White”) was born at Llanilloes, Montgomeryshire, Wales. He studied at Oxford and then at St John’s College, Cambridge, but his studies were interrupted in 1558 when Elizabeth I ascended the throne and Catholics were expelled from the universities.

He returned to Wales and became a teacher, first at Overton in Flintshire, then at Wrexham and other places, acquiring a considerable reputation as a Welsh scholar. He married and had six children, three of whom survived him. He was pressured to become an Anglican and succumbed briefly, but returned to the Catholic faith after a sudden illness and remained steadfast in it thereafter, about the same time as Catholic priests came back to Wales.

His adherence to the old faith was noted by the Bishop of Chester, who brought pressure on him to conform to the Anglican faith. It is recorded in an early account of his life that:

“…[a]fter some troubles, he yielded to their desires, although greatly against his stomach … and lo, by the Providence of God, he was no sooner come out of the church but a fearful company of crows and kites so persecuted him to his home that they put him in great fear of his life, the conceit whereof made him also sick in body as he was already in soul distressed; in which sickness he resolved himself (if God would spare his life) to return to a Catholic.”

He frequently had to change his home and place of work to avoid fines and imprisonment, but he was finally arrested in 1579 and imprisoned in Ruthin gaol (jail). He was offered his freedom if he would conform. After escaping and spending a year and a half on the run, he spent the rest of his life in prison. He was fined astronomical sums for not attending the Anglican church services (recusancy), and was carried to church in irons more than once; but he would disrupt the service by rattling his irons and heckling, which led to further astronomical fines, but was not otherwise useful. Furious at him, his jailers put him in the stocks for many hours where many people came to abuse and insult and spit on him.

Taunted by a local Anglican priest who claimed that the keys of the Church were given no less to him than to St. Peter. “There is this difference”, Gwyn replied, “namely, that whereas Peter received the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, the keys you received were obviously those of the beer cellar.” The queen’s men wanted him to give them the names of other Catholics, but Richard would not do so.

Gwyn was fined £280 for refusing to attend Anglican church services, and another £140 for “brawling”, while in chains, when they took him there. When asked what payment he could make toward these huge sums, he answered, “Six-pence”. Gwyn and two other Catholic prisoners, John Hughes and Robert Morris, were ordered into court in the spring of 1582 where, instead of being tried for an offence, they were given a sermon by an Anglican minister. However, they started to heckle him (one in Welsh, one in Latin and one in English) to the extent that the exercise had to be abandoned.

In 1580 he was transferred to Wrexham, where he suffered much persecution, being forcibly carried to the Church of England service, and being frequently taken to court at different assizes to be continually questioned, but was never freed from prison; he was removed to the Council of the Marches, and later in the year suffered torture at Bewdley and Bridgenorth before being sent back to Wrexham. There he remained a prisoner till the Autumn Assizes, when he was brought to trial on 9 October, found guilty of treason and sentenced to be executed. At his trial, men were paid to lie about him, as one of them later admitted. The men on the jury were so dishonest that they asked the judge whom he wanted them to condemn.

Richard Gwyn, John Hughes and Robert Morris were indicted for high treason in 1584 and were brought to trial before a panel headed by the Chief Justice of Chester, Sir George Bromley. Witnesses gave evidence that they retained their allegiance to the Catholic Church, including that Gwyn composed “certain rhymes of his own making against married priests and ministers” and “[T]hat he had heard him complain of this world; and secondly, that it would not last long, thirdly, that he hoped to see a better world [this was construed as plotting a revolution]; and, fourthly, that he confessed the Pope’s supremacy.” The three were also accused of trying to make converts.

Again his life was offered him on condition that he acknowledge the queen as supreme head of the Church. His wife, Catherine, and one of their children were brought to the courtroom and warned not to follow his example. She retorted that she would gladly die alongside her husband; she was sure, she said, that the judges could find enough evidence to convict her if they spent a little more money. She consoled and encouraged her husband to the last. He suffered on 16 October 1584, where he was hung, drawn, and quartered. On the scaffold he stated that he recognised Elizabeth as his lawful queen but could not accept her as head of the Church in England.

Just before Gwyn was hanged he turned to the crowd and said, “I have been a jesting fellow, and if I have offended any that way, or by my songs, I beseech them for God’s sake to forgive me.” The hangman pulled on his leg irons hoping to put him out of his pain. When he appeared dead they cut him down, but he revived and remained conscious through the disembowelling, until his head was severed. He cried out in pain, “Holy God, what is this?” To which he was replied, “An execution of her majesty the queen.” His last words, in Welsh, were reportedly “Iesu, trugarha wrthyf” (“Jesus, have mercy on me”). The beautiful religious poems, four carols and a funeral ode, Richard wrote in prison are still in existence. In them, he begged his countrymen of Wales to be loyal to the Catholic faith.

We can greatly admire St. Richard for his bravery. His willingness to suffer for what he believed in is inspiring. Let’s ask St. Richard to make us as strong in our convictions as he was. Relics of St Richard Gwyn are to be found in the Cathedral Church of Our Lady of Sorrows, seat of the Bishop of Wrexham and also in the Catholic Church of Our Lady and Saint Richard Gwyn, Llanidloes.

The incident of the birds mentioned in Richard’s “Early life” here is one of several strange events in Richard Gwyn’s life. Once when he was brought before a court, the clerk who read the indictment suddenly lost his vision and had to be replaced before the proceedings could resume. The judge cautioned those present not to report the incident, so that Catholics could not claim that it was a miracle. On another occasion, the judge, who later sentenced Richard to death, became inexplicably speechless in court.

St Richard Gwyn, faithful husband, father, and Catholic, pray for us!

Love,

Matthew