St Peter Canisius, SJ, is my patron saint and my hero of catechesis. When I am frustrated, I paraphrase him in a one line prayer: “Why don’t you try explaining it to them?” It REALLY helps ME understand it, too, first of all. 🙂

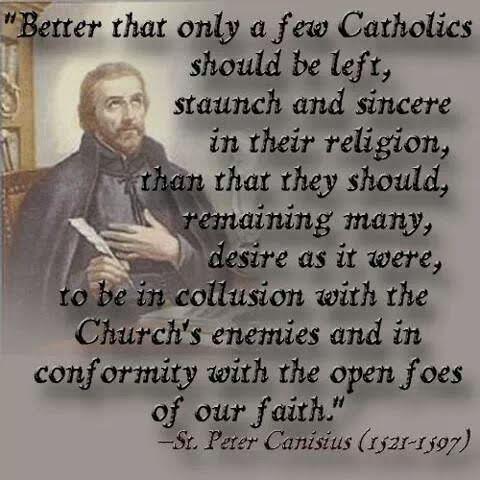

The Roman Catholic Church sees the divisions among Christians as scandalous. It believes the Lord views these divisions similarly. The Church seeks to heal these divisions. Jn 17:21-23. Divisions in Christianity are a disincentive to non-Christians to consider Jesus Christ and an impediment to Christian agape among Christians.

It is reported Gandhi read the New Testament every day. Upon seeing this, a British reporter asked if The Mahatma, Great Soul, intended to become Christian. Gandhi responded he would if he ever met one. “You’re Christ I like” he said.

The energetic life of Peter Canisius should demolish any stereotypes we may have of the life of a saint as dull or routine. Peter lived his 76 years at a pace which must be considered heroic, even in our time of rapid change. A man blessed with many talents, Peter is an excellent example of the scriptural man who develops his talents for the sake of the Lord’s work. The restoration of the Catholic Church in Germany after the Reformation is attributed to his work. He was one of the most important figures in the Catholic Reformation in Germany. His was such a key role that he has often been called the “second apostle of Germany” in that his life parallels the earlier work of St Boniface (June 5).

Both Holland and Germany claim him as their son, for Nijmegen, then in the Duchy of Guelders (until 1549 part of the Spanish Netherlands within the Holy Roman Empire) where he was born, Peter Kanis, May 8th, 1521, though a Dutch town today, was at that time in the ecclesiastical province of Cologne and had the rights of a German city.

“In an account known as his Confessions (c. 1570) and his Testament (c.1596), St. Peter Canisius accuses himself as a boy of contentiousness, fits of anger, jealousies, secret hatreds, arrogance, inconsiderate expressing of opinions on weighty matters, “like a blind man discoursing of colors,” and carelessness in resisting temptations against purity arising from thought, desire and the conversation of the boys he associated with. His intense humility can be expected to underscore his faults, but his words tells us that he did have a nature that needed to be tamed and controlled. In early youth he also had the inclination occasionally to be deeply stirred spiritually and to give signs of his future vocation by playing priest, acting out the Mass, preaching, singing and praying, all this sometimes before a group of playmates. He also liked to serve Mass. (Confessions, p. 12 of Braunsberger, Vol.1)”

-St Peter Canisius, SJ, as edited by Fr. Christopher Rengers, O.F.M. Cap., The 33 Doctors of the Church, (Tan Books: 2000)

Peter’s mother, Ægidia van Houweningen, died shortly after Peter’s birth. His father, Jacob Kanis, a Catholic and nine times burgomaster of Nijmegen, sent him at the age of fifteen to the University of Cologne, where he met the saintly young priest, Nicolaus van Esch. It was he who drew Canisius into the orbit of the loyal Catholic party of Cologne, which had been formed in opposition to the archbishop, Hermann von Wied, who had secretly gone over to the Lutherans. Canisius was chosen by the group to approach the emperor, and the deposition of the archbishop which followed averted a calamity from the Catholic Rhineland.

St Peter Canisius exerted a strong influence on Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I; he ceaselessly reminded Ferdinand of the imminent danger to his soul should he concede more rights to Protestants in return for their military support. When Peter Canisius sensed a very real danger of Ferdinand’s son and heir, King Maximilian, openly declaring himself a Protestant, he convinced Emperor Ferdinand to threaten disinheritance should Maximilian desert the Catholic Faith.

Although Peter once accused himself of idleness in his youth, he could not have been idle too long, for at the age of 19 he received a master’s degree from the university at Cologne. Soon afterwards he met Blessed Peter Faber, SJ, the first disciple of Ignatius Loyola, and underwent the Spiritual Exercises under his direction. Faber influenced Peter so much that he joined the recently formed Society of Jesus.

At this early age Peter had already taken up a practice he continued throughout his life—a process of study, reflection, prayer and writing. After his ordination in 1546, he became widely known for his editions of the writings of St. Cyril of Alexandria and St. Leo the Great. Besides this reflective literary bent, Peter had a zeal for the apostolate. He could often be found visiting the sick or prisoners, even when his assigned duties in other areas were more than enough to keep most people fully occupied.

His obedience was tested when he was sent by St Ignatius to teach rhetoric in the comparative obscurity of the new Jesuit college at Messina, but this interlude in his public work for the church was but a brief one. In 1547 Peter attended several sessions of the Council of Trent, whose decrees he was later assigned to implement, as procurator for the bishop of Augsburg. (I was the novice “procurator”. I LIKED that job. Tell you about it sometime.)

Recalled to Rome in 1549 to make his final profession in the presence of St Ignatius of Loyola himself who was his spiritual director and traveling companion and the founder of the Society of Jesus, he was entrusted with what was to become his life’s work: the mission to Germany.

At the request of the duke of Bavaria, Canisius was chosen with two other Jesuits to profess theology in the University of Ingolstadt. Soon he was appointed rector of the University, and then, through the intervention of King Ferdinand of the Romans, he was sent to do the same kind of work in the University of Vienna.

Called to Vienna to reform their university, he couldn’t win the people with preaching or fancy words spoken in his German accent. He won their hearts by ministering to the sick and dying during a plague. His success was such that the king tried to have him appointed to the archbishopric. Though he refused this dignity, he was compelled to administer the diocese for the space of a year. During Mass one day he received a vision of the Sacred Heart of Jesus , and ever after offered his work to the Sacred Heart. Winning! (in the good, healthy sense) 🙂

It was at this period, 1555, that he issued his famous Catechism, one of his greatest services to the Church. With its clear and popular exposition of Catholic doctrine it met the need of the day, and was to counter the devastating effect of Luther’s Catechism. In its enlarged form it went into more than four hundred editions by the end of the seventeenth century and was translated into fifteen languages.

For many years during the Protestant Reformation, Peter saw the students in his universities swayed by the flashy speeches and the well-written arguments of the Protestants. Peter was not alone in wishing for a Catholic catechism that would present true Catholic beliefs undistorted by fanatics. Finally King Ferdinand himself ordered Peter and his companions to write a catechism. This hot potato got tossed from person to person until Peter and his friend Fr. Lejay were assigned to write it. Lejay was obviously the logical choice, being a better writer than Peter. So Peter relaxed and sat back to offer any help he could. When Father Lejay died, King Ferdinand would wait no longer. Peter said of writing: “I have never learned to be elegant as a writer, but I cannot remain dumb on that account.” The first issue of the Catechism appeared in 1555 and was an immediate success. Peter approached Christian doctrine in two parts: wisdom — including faith, hope, and charity — and justice — avoiding evil and doing good, linked by a section on sacraments.

Because of the success and the need, Peter quickly produced two more versions: a Shorter Catechism for middle school students which concentrated on helping this age group choose good over evil by concentrating on a different virtue each day of the week; and a Shortest Catechism for young children which included prayers for morning and evening, for mealtimes, and so forth to get them used to praying.

As intent as Peter was on keeping people true to the Catholic faith, he followed the Jesuit policy that harsh words should not be used, that those listening would see an example of charity in the way Catholics acted and preached. However, his companions were not always as willing. He showed great patience and insight with one man, Father Couvillon. Couvillon was so sharp and hostile that he was alienating his companions and students. Anyone who confronted him became the subject of abuse. It became obvious that Couvillon suffered from emotional illness. But Peter did not let that knowledge blind him to the fact that Couvillon was still a brilliant and talented man. Instead of asking Couvillon to resign he begged him to stay on as a teacher and then appointed him as his secretary. Peter thought that Couvillon needed to worry less about himself and pray more and work harder. He didn’t coddle him but gave Couvillon blunt advice about his pride. Coming from Peter this seemed to help Couvillon. Peter consulted Couvillon often on the business of the Province and asked him to translate Jesuit letters from India. Thanks to Peter , even though Couvillon continued to suffer depression for years, he also accomplished much good.

In his fight with German Protestantism, Canisius requested much more flexibility from Rome. “If you treat them right, the Germans will give you everything. Many err in matters of faith, but without arrogance. They err the German way, mostly honest, a bit simple-minded, but very open for everything Lutheran. An honest explanation of the faith would be much more effective than a polemical attack against reformers.” He rejected Catholic attacks against Calvin and Melanchton by saying, “With words like these, we don’t cure patients, we make them incurable.”

From Vienna, Canisius passed on to Bohemia, where the condition of the church was desperate. In the face of determined opposition he established a college at Prague which was to develop into a university. Named Provincial of southern Germany in 1556, he established colleges for boys in six cities, and set himself to the task of providing Germany with a supply of well-trained priests. This he did by his work for the establishment of seminaries, and by sending regular reinforcements of young men to be trained in Rome.

On his many journeys in Germany St Peter Canisius, SJ never ceased from preaching the word of God. He often encountered apathy or hostility at first, but as his zeal and learning were so manifest great crowds soon thronged the churches to listen. For seven years he was official preacher in the cathedral of Augsburg, and is regarded in a special way as the apostle of that city. Whenever he came across a country church deprived of its pastor, he would halt there to preach and to administer the sacraments. It seemed impossible to exhaust him: ‘If you have too much to do, with God’s help you will find time to do it all,’ he said, when someone accused him of overworking himself.

Another form of his apostolate was letter writing, and the printed volumes of his correspondence cover more than eight thousand pages. Like St Bernard of Clairvaux he used this means of comforting, rebuking and counseling all ranks of society. As the needs of the church or the individual required, he wrote to pope and emperor, to bishops and princes, to ordinary priest and laymen. Where letters would not suffice he brought to bear his great powers of personal influence. Thus at the conference between Catholics and Protestants held at Worms in 1556, it was due to his influence that the Catholics were able to present a united front and resist Protestant invitations to compromise on points of principle. In Poland in 1558 he checked an incipient threat to the traditional faith of the country; and in the same year, he earned the thanks of Pope Pius IV for his diplomatic skill in healing a breach between the pope and the emperor. This gift of dealing with men led to his being entrusted in 1561 with the promulgation in Germany of the decrees of the council of Trent.

Shortly afterwards he was called on to answer the Centuries of Magdeburg. This work, ‘the first and worst of all Protestant church histories,’ was a large-scale attack on the Catholic church, and its enormous distortions of history would have required more than one mar to produce an adequate answer. Yet Peter Canisius showed the way by his two works, The History of John the Baptist, and, also theologically defended Catholic Mariology in, The Incomparable Virgin Mary/Opus Marianum, or “De Maria Virgine Incomparabili et Dei Genitrice Sacrosancta Libri Quinque”, receiving high praise from St John Eudes as a Marian teacher.

Canisius taught that while there are many roads leading to Jesus Christ, Marian veneration is the best way to him. His sermons and letters document a clear preoccupation with Marian veneration. Under the heading “prayer” he explains the Ave Maria, Hail Mary, as the basis for Catholic Marian piety. Less known are his Marian books, in which he published prayers and contemplative texts. He is credited with adding to the Hail Mary the sentence “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners.” Eleven years later it was included in the Catechism of the Council of Trent of 1566.

In 1565, the Vatican was looking for a nuncio to deliver the decrees of the Council of Trent to the loyal bishops of Germany. What would be a simple errand in our day, was a dangerous assignment in the sixteenth century. The first envoy who tried to carry the decrees through territory of hostile Protestants and vicious thieves was robbed of the precious documents. Rome needed someone courageous but also someone above suspicion. They chose Peter Canisius, who had reformed German universities from heresy. At 43 he was a well-known Jesuit who had founded colleges that even Protestants respected. They gave him a cover as official “visitor” of Jesuit foundations. But Peter couldn’t hide the decrees like our modern fictional spies with their microfilmed messages in collar buttons or cans of shaving cream. Peter traveled from Rome and crisscrossed Germany successfully loaded down with the Tridentine tomes — 250 pages each — not to mention the three sacks of books he took along for his own university!

Renowned as a popular preacher, Peter packed churches with those eager to hear his eloquent proclamation of the gospel. He had great diplomatic ability, often serving as a reconciler between disputing factions. In his letters (filling eight volumes) one finds words of wisdom and counsel to people in all walks of life. At times he wrote unprecedented letters of criticism to leaders of the Church—yet always in the context of a loving, sympathetic concern.

At 70 Peter suffered a paralytic seizure, but he continued to preach and write with the aid of a secretary until his death in his hometown (Nijmegen, Netherlands) on December 21, 1597. His body was interred before the high altar of the Church of Saint Nicholas in Fribourg. His relics were translated to the Church of Saint Michael at the Jesuit College in Fribourg in 1625.

From 1580 until his death in 1597 he labored and suffered much in Switzerland. His last six years were spent in patient endurance and long hours of prayer in the college of Fribourg, now that broken health had made further active work impossible. Soon after his death, December 21st, 1597, his tomb began to be venerated, and numerous miracles were attributed to his intercession. He had the unique honor of being canonized and declared a doctor of the church on the same day, June 21st, 1925.

Peter’s untiring efforts are an apt example for those involved in the renewal of the Church or the growth of moral consciousness in business or government. He is regarded as one of the creators of the Catholic press, and can easily be a model for the Christian author or journalist. Teachers can see in his life a passion for the transmission of truth. Whether we have much to give, as Peter Canisius did, or whether we have only a little to give, as did the poor widow in the Gospel (see Luke 21:1–4), the important thing is to give our all. It is in this way that Peter is so exemplary for Christians in an age of rapid change when we are called to be in the world but not of the world.

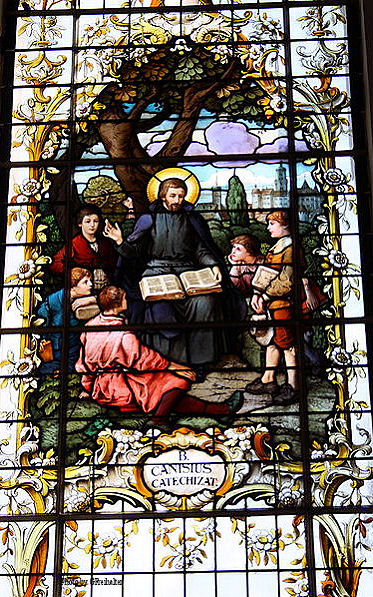

-by Franz Xavier Zettler, 1911, in Munich

“It was as if You opened to me the Heart in Your most Sacred Body; I seemed to see it directly before my eyes. You told me to drink from this fountain, inviting me, that is, to draw the waters of my salvation from Your wellsprings, my Savior. I was most eager that streams of faith, hope and love should flow into me from that Source. I was thirsting for poverty, chastity, obedience. I asked to be made wholly clean by You, to be clothed by You, to be made resplendent by You…So, after daring to approach Your most loving Heart, and to plunge my thirst into it, I received a promise from You of a garment made of three parts: these were to cover my soul in its nakedness, and to belong especially to my religious profession. They were peace, love, and perseverance. Protected by this garment of salvation, I was confident that I would lack nothing but all would succeed and give You glory.””

–St. Peter Canisius, SJ, before he set out for Germany, having received the apostolic blessing, describing the profound spiritual experience he underwent

With sincere Marian devotion, St. Peter wrote the following words to his step-Mother:

“Dear Mother,

I am sending you a picture of Our Lady as a pledge of affectionate remembrance. May it serve you as a mirror and bring you comfort when sorrow floods into your soul. All her life long holy Mother Mary endured a thousand sorrows and anxieties on account of her dear Son, because even while He was still a child she saw clearly in the light of her heavenly meditations all the sufferings that awaited His tender limbs. Her tears used to fall on the little hands and feet that one day great nails would violently pierce, and she used to kiss the holy brow destined for its crown of thorns. So, dearest Mother, offer up all your affliction in union with the sorrows of the holy Mother of God. Place all your troubles and anxieties in the stricken heart of the Queen of Heaven, for she can protect you better than could all mankind put together. Do not take so much to heart what cannot now be changed.”

-St Peter Canisius, SJ, as edited by Fr. James Brodrick, SJ, (Jesuit Way — an imprint of Loyola Press) 62.

Resolution:

St. Peter sent his mother an image of Our Lady and counseled her to turn all her troubles and anxieties over to the stricken heart of the Queen of Heaven. Today, when I see my image of Our Lady, I will follow the advice of St. Peter Canisius, Doctor of the Church, and turn my troubles over to Our Lady.

Marian Vow:

Consecration to the Immaculate is a daily process. St. Peter Canisius reminds us in his commentary on the Hail Mary that our Lady already watches over us in a daily way:

“To be sure, walking in the footsteps of the Holy Fathers, we not only salute the praiseworthy and admirable Virgin, who is as a lily among thorns, but we also believe and profess her to be endowed with such great power that she can listen to, assist and favor poor mortals as long as they especially commend themselves and their desires to her and suppliantly expect daily grace through her motherly intercession.”

-St Peter Canisius, SJ, as edited by Fr. Christopher Rengers, O.F.M. Cap., The 33 Doctors of the Church, (Tan Books: 2000), p. 473.

Prayer

Saint Peter Canisius, you saw the good in even the most troublesome of people. You found their talents and used them. Help me to see beyond the behavior of others that may bother me to the gifts God has given them. Amen.

Love,

Matthew