-by Trent Horn

“Why confess your sins to a priest when you can just confess them straight to God?”

At one time or another, most Catholics have heard this objection from their Protestant friends. They may have even heard it from a fellow Catholic who doesn’t understand the importance of the sacrament of reconciliation (or confession).

But when these critics are asked to provide biblical evidence for the claim that we should confess our sins only in private prayer to God, they often come up empty-handed save for one verse: 1 John 1:9. Consider a comment that Franklin Graham, the influential son of the famous Rev. Billy Graham, made on his Facebook page regarding priests being able to forgive sins:

The Bible says, “If we confess our sins, He (God) is faithful and just to forgive us our sins, and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9). As a sinner, I’m glad we can go directly to God for forgiveness 24/7, on any day, in any year. He sent His Son Jesus Christ to pay the price for sin with His shed blood on the Cross of Calvary.

Let’s examine where Mr. Graham, and many critics like him, go wrong when they rely on this verse to disprove the sacrament Christ gave us for the forgiveness of sins.

Agree to disagree

Catholics agree with Protestants such as Graham that “only God forgives sins. Since he is the Son of God, Jesus says of himself, ‘The Son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins’ and exercises this divine power: ‘Your sins are forgiven’” (Catechism of the Catholic Church 1441). Where we disagree, is that, as the Catechism goes on to say, “by virtue of [Christ’s] divine authority he gives this power to men to exercise in his name.”

1 John 1:9 does not refute the concept of sacramental confession, because this verse does not say we should confess our sins only in private prayer addressed to God. 1 John 1:9 refers to the practice of “confessing our sins”—it does not say to whom or how we should make our confession. Graham and other Protestants assume that because only God can forgive sins it follows that if we confess our sins directly to God, apart from any human intermediary, then we will always be forgiven.

But consider 1 John 2:23, which says, “[W]hoever confesses the Son has the Father also.” If you read only this verse you might think John is referring to the confession of our belief in the Son to the Father. In context, 1 John 2 is a warning to Christians about the anti-Christ. John says we can know who the anti-Christ is because he either publicly denies the Son or he does not confess to believing in him.

Likewise, 1 John 1 refers to those who publicly deny they are sinners or publicly claim to be Christians while still sinning (or those whom John says “walk in darkness”). Since both verse 8 and verse 10 refer to certain Christians who erroneously tell other people they do not sin, this means that, at the least, John has not excluded the context of confessing sins to other people in verse 9.

I confess

This may even be John’s primary meaning, since both 1 John 1:9 and 1 John 2:23 contain the same Greek verb, homologeō, that is translated “confess.” This word means “I confess, profess, acknowledge, praise” and is used twenty-six times in the New Testament. Each time it is used, with one exception, it refers to a person publicly declaring something to another human being.

Here’s a breakdown of how it’s used in the New Testament outside of 1 John 1:9:

- God’s promise he spoke to Abraham (Acts 7:17)

- Jesus confessing to damned hypocrites what their fate will be (Matthew 7:23)

- John the Baptist confessing to the Jewish leaders that he is not the Christ (John 1:20)

- The Jewish leaders not confessing aloud their internal belief in Jesus (John 12:42)

- Christians confessing their beliefs to other people (Matthew 10:32, Luke 12:8, John 9:22, Acts 24:14, Romans 10:9-10, 1 Timothy 6:12, Titus 1:16, 1 John 2:23, 1 John 4:2, 1 John 4:15)

- Non-Christians making promises, declarations, or confessions of belief/disbelief to other people (Matthew 14:7, Acts 23:8, Hebrews 11:13, 1 John 4:3, 2 John 1:7)

The lone exception is Hebrews 13:15, which refers to the lips of Christians that “acknowledge his name” or make a confession of faith to God. Let me reiterate this point: the Greek verb translated “confess” in 1 John 1:9 is never used in the New Testament to describe confessing sins to God. Aside from Hebrews 13:15, homologeō is never used to describe confessing anything to God. In John’s writings especially, it is always used to describe confessing a belief to other human beings.

Scholarly support

This understanding of confession in the first epistle of John is not new. The nineteenth-century Anglican New Testament scholar Brooke Westcott (who helped create the Greek New Testament scholars still study today) said that the phrase “confess our sins” means “not only acknowledge them, but acknowledge them openly in the face of men” (The Epistles of St. John, 23).

Hans-Josef Klauck, a prolific New Testament scholar, likewise held that 1 John 1:9 referred to some kind of public, liturgical confession of sin (Erste Johannesbrief, 94-95). The Johannine New Testament scholar David Rensberger writes in his recent commentary on John’s letters:

Confession of sin was generally public (Mark 1:5; Acts 19:18; James 5:16; Didache 4:14, 14:1), and that may well be the case here. The use of the plural “sins” (rather than “sin,” as in 1:8) is a reminder that not just an abstract confession of sinfulness but the acknowledgement of specific acts is in mind (Abingdon New Testament Commentary 1,2,3 John, 54).

Notice Rensberger’s citation of the Didache, which was a first-century catechism. It gave believers the following instruction: “In your gatherings, confess your transgressions, and do not come for prayer with a guilty conscience” (4:14). Scholars tend to date 1 John as being written in the late A.D. 90s and the Didache as having been written at the same time or even earlier. It makes sense, therefore, to connect John’s instruction to “confess your sins” with the context of public confession in the early Church described in the Didache.

Fr. Raymond Brown, who was a moderate in the field of biblical studies, reached the same conclusion in his Anchor Bible commentary on 1 John. After listing the public confession of sins in the Old Testament to which John is alluding (Leviticus 5:5-6, Proverbs 28:13, Sirach 4:25-26, Daniel 9:20) he writes, “All the parallels and background given thus far suggest that the Johannine expression refers to a public confession rather than a private confession by the individual to God” (The Epistles of John, 208).

Other Protestant commenters such as Robert Yarbough admit that public confession is a possible way to interpret this verse, even if they don’t accept it as the verse’s primary meaning (1, 2, 3 John, 63).

Confessing sins to one another

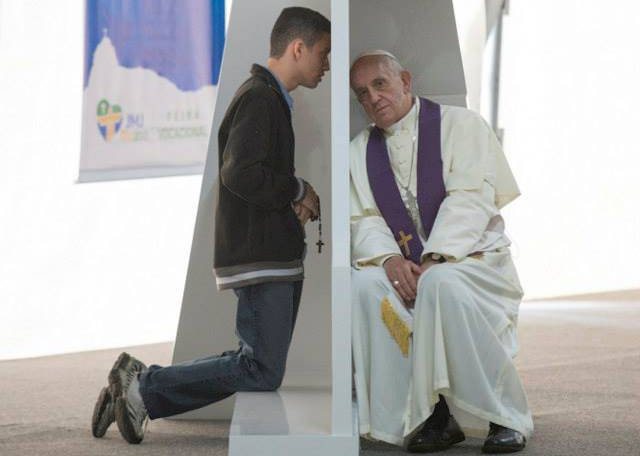

The Catechism says that even though the disciplines related to the sacrament of confession have changed over time (public confession in the church transitioned into private confession to a priest in the seventh century), the sacrament has always maintained a certain fundamental structure. Specifically, the sacrament includes the sinner expressing repentance for his sins and God, working through the ministers of the Church, healing the sinner and reestablishing him in ecclesial communion with the Body of Christ (CCC 1447-1448).

The only passage in the New Testament that instructs Christians to confess their sins is James 5:16, which says, “Therefore confess your sins to one another [emphasis added], and pray for one another, that you may be healed. The prayer of a righteous man has great power in its effects.”

The word rendered “confess” in this passage is exomologeó and, while it does refer to confessing praise or thanksgiving directly to God (Matthew 11:25, Luke 10:21, Romans 14:11), it never refers to confessing sins to God. Like homologeó, this verb primarily describes public confessions or declarations to other humans (e.g., Luke 22:6, Acts 19:8, Romans 15:9, and Philippians 2:11, though this last verse might also refer to confessing belief in Jesus directly to God as well as to other humans).

James says in 5:14-15 that if a sick man receives anointing from the elders (Greek, presbuteroi, from which we derive the English word priest) the man’s sins will be forgiven. The context in James is clear: God alone saves the sick and forgives sinners, but God has chosen to use human intermediaries—priests—in order to administer sacraments like the anointing of the sick or reconciliation.

Most Protestants would even agree with this thinking on something like baptism, since they tend to deny the validity of self-baptism (something Catholics also deny). Those who believe in baptismal regeneration correctly insist that while God alone takes away sin in baptism, God does not act alone when he takes away a person’s sins. Instead, God works through other believers who baptize on God’s behalf (e.g., Acts 8:38, where Philip baptized the Ethiopian eunuch).

In a similar way, the Church teaches that the apostles and their successors were entrusted with the ministry of reconciliation (see 2 Corinthians 5:18), and Jesus explicitly gave the apostles the power to not just preach the forgiveness of sins but to actually forgive or retain sins (John 20:23). The Catechism says:

The office of binding and loosing which was given to Peter (Matt. 16:18-19) was also assigned to the college of the apostles united to its head. The words bind and loose mean: whomever you exclude from your communion will be excluded from communion with God; whomever you receive anew into your communion God will welcome back into his. Reconciliation with the Church is inseparable from reconciliation with God (CCC 1444-1445).

Of course, in order for the apostles to know if someone needs reconciliation with God or if the person’s sins should be retained, they would have to know what the person’s sins were. Barring some kind of revelation from God, this knowledge could come only from a person confessing his sins aloud, or what is called auricular confession.

24/7 confession?

But what about Graham’s point that Christians should be able to seek forgiveness of sins “24/7,” anytime and anywhere, without having to go through an intermediary? First, Catholics wholeheartedly agree that we should confess our sins directly to God whenever we feel guilty (CCC 1458). The Code of Canon Law describes situations where a person seeks forgiveness of sins outside the context of confession:

A person who is conscious of grave sin is not to celebrate Mass or receive the body of the Lord without previous sacramental confession unless there is a grave reason and there is no opportunity to confess; in this case the person is to remember the obligation to make an act of perfect contrition which includes the resolution of confessing as soon as possible (CIC 916).

An act of perfect contrition (which is sorrow for sin out of love for God) is sufficient to warrant forgiveness of sins. If a person sought the sacrament of confession but died before reaching it he could still be saved through his desire to repudiate sin and trust in God’s mercy.

However, just as the efficacious nature of baptism of desire does not nullify the normal duty to be baptized with water by another person, the efficacious nature of confessing sins directly to God does not nullify the normal duty we have to seek out a minister of the Church who can validly perform the sacrament of reconciliation.

Conclusion

The Bible does not teach that the norm for seeking reconciliation with God and his Church is private, unconditional forgiveness of sins. At the very least, 1 John 1:9 does not teach this doctrine. Instead, 1 John 1:9 uses the Greek word homologeō, which always refers to a person publicly confessing something he believes.

Instead, the Bible tells us to confess our sins to one another (James 5:16), and especially to priests who can administer sacraments that absolve our sin (James 5:14-15). We know priests have this ability because their authority comes from the apostles who had the authority to “bind and loose” what is in heaven (Matt. 16:18-19) and to forgive or retain sins (John 20:23).

The early Church understood that the promise of God’s forgiveness in 1 John 1:9 did not preclude but rather included the sacrament of reconciliation. As St. Cyprian of Carthage put it in A.D. 251, “[W]ith grief and simplicity confess this very thing to God’s priests, and make the conscientious avowal, put off from them the load of their minds, and seek out the salutary medicine even for slight and moderate wounds” (The Lapsed, 28).”

“Confession heals, confession justifies, confession grants pardon of sin. All hope consists in confession. In confession there is a chance for mercy. Believe it firmly, do not doubt, do not hesitate, never despair of the mercy of God.”

— St. Isidore of Seville, Doctor of the Church

“It is necessary to confess our sins to those to whom the dispensation of God’s mysteries is entrusted. Those doing penance of old are found to have done it before the saints. It is written in the Gospel that they confessed their sins to John the Baptist [Matt. 3:6], but in Acts [19:18] they confessed to the apostles.” –St Basil the Great (Rules Briefly Treated, 288 [A.D. 374])

Love & sincere contrition & sorrow for my sins,

Matthew