The uprising by the “Society for Justice and Harmony” (commonly known as the “Boxers”; don’t you just LOVE these euphemisms? Not well disguised, except from the truly moronic? “The Committee on Public Safety” in the French Revolution? Pick a lobby in Washington? Ok, I’ll cede one, “The Holy Office”, aka, The Inquisition :), occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century and caused the shedding of the blood of many Christians, Catholic & Protestant.

After a long drought, a slight drizzle began to moisten the dry fields of Shanxi province. But it was too late. Local peasants had already spread rumors – the Christians were to blame for the long-term lack of rain. Banners had begun to appear throughout the region: “The skies won’t rain, the earth is scorched, all because the churches have blocked the heavens” (Taiyuan jiaochu jianhua, 311).

Two Franciscan bishops, two priests, a brother, and seven nuns had prayed for rain, but when it had finally arrived they knew it could not stop the tide of violence. Chinese Christians all around them were already being captured, ordered to renounce their faith in God, and executed if they refused. By the summer of 1900 a group of anti-foreign and anti-Christian men and women had organized themselves into roaming bands of martial artists groups carrying long swords, spears, and halberds; they called themselves the Yihetuan, or the “Society of Righteous Harmony.” Their duty, they asserted, was to support the ruling court and “annihilate all foreigners.”

At 4 o’clock in the afternoon, the Franciscan bishops, priests, and nuns were reciting the Divine Office together with Chinese faithful in Taiyuan, the capital of Shanxi, when they heard the clamor of weapons approaching their small room. Instinctively knowing that they would soon be executed, those present all knelt before Bishop Gregorius Grassi, the ordinary of their remote Chinese diocese. Grassi trembled with emotion as he said to his fellow Christians, “The hour of death has come, my children: kneel down and I will give you holy absolution” (Franciscan Martyrs of the Boxer Rising, 14).

Bishops Grassi and Francis Fogolla, Fathers Theodiric Balat and Elias Fachini, Brother Andreus Bauer, seven nuns, fourteen Chinese Catholics, and a group of Protestants who had also been arrested, were each stripped to the waist, men and women, and tied together. On their way to the governor’s mansion, where their execution ground was being prepared, the Franciscans were derided and beaten both by their guards and the mob that lined the street.

Once they had arrived at Governor Yuxian’s official residence, the missionaries and native Catholics were ordered to kneel in the large courtyard. There was no trial. In Cardinal Louis Nazaire Bégin’s account of what happened next, we hear of how they were martyred:

‘Kill them, kill them!’ roared the crowd. Yu-Hsien striking with his own sword cried: ‘Kill them!’ At this sight the soldiers began the slaughter, dealing blows right and left, cruelly injuring their victims before giving the final stroke. Father Elie, aged sixty-one years, received more than one hundred sword cuts and at each lifted his eyes to heaven saying: ‘I go to heaven.’

During the scene the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary were spectators, for their executioners hoped the sight of the martyred priests would make their own death more horrible. They knelt in prayer with eyes lifted to heaven, praying for the martyrs, for the conversion of their persecutors and for the perseverance of the Christians. . . . The nuns embraced each other, intoned St Ambrose & St Augustine’s Te Deum Laudamus (Christian martyrs, when presented with immanent death, SING! see also Carmelites of the French Revolution), and presented their heads to the executioners…(Life of Mother Marie Hermine, 62-63).

Father Andrew Wang tried to evade the Boxers by wearing secular garb and taking flight into Shanxi’s remote areas. Father Wang spent several days without food or shelter, and finally in a state of exhaustion, coughing blood, was discovered by his pursuers, who took him to the local magistrate for trial.

During his investigation, he was told by the local official: “. . . if you renounce your religion you will receive clothes and money, and your life will be spared.” Father Wang calmly informed his judge that he was a priest, reasserted his faith in God, and asked to be executed on the grounds of his church, which had just been destroyed by the Boxers.

The Boxer Rebellion, Boxer Uprising or Yihetuan Movement was a violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian movement which took place in China towards the end of the Qing dynasty between 1898 and 1900. It was initiated by the Militia United in Righteousness (Yihetuan), known in English as the “Boxers”, and was motivated by proto-nationalist sentiments and opposition to foreign imperialism and Christianity. The Great Powers intervened and defeated Chinese forces.

The uprising took place against a background of severe drought, and the disruption caused by the growth of foreign spheres of influence. After several months of growing violence against foreign and Christian presence in Shandong and the North China plain, in June 1900 Boxer fighters, convinced they were invulnerable to foreign weapons, converged on Beijing with the slogan “Support the Qing, exterminate the foreigners.”

Foreigners and Chinese Christians sought refuge in the Legation Quarter. In response to reports of an armed invasion to lift the siege, the initially hesitant Empress Dowager Cixi supported the Boxers and on June 21 authorized war on foreign powers. Diplomats, foreign civilians and soldiers, and Chinese Christians in the Legation Quarter were under siege by the Imperial Army of China and the Boxers for 55 days. Chinese officialdom was split between those supporting the Boxers and those favoring conciliation, led by Prince Qing.

The supreme commander of the Chinese forces, Ronglu, later claimed that he acted to protect the besieged foreigners. The Eight-Nation Alliance, after being initially turned back, brought 20,000 armed troops to China, defeated the Imperial Army, and captured Beijing (Peking) on August 14, lifting the siege of the Legations. Uncontrolled plunder of the capital and the surrounding countryside ensued, along with the summary execution of those suspected of being Boxers.

The Boxer Protocol of September 7, 1901 provided for the execution of government officials who had supported the Boxers, provisions for foreign troops to be stationed in Beijing, and an indemnity of 450 million taels of silver – more than the government’s annual tax revenue, to be paid as indemnity over a course of thirty-nine years to the eight nations involved.

As a result of the Boxer Rebellion, the martyrdom of Catholic & Protestant missionaries and many Chinese took place who can be grouped together as follows. Twenty-seven Franciscans and Franciscan tertiaries and their confreres in faith who became victims of the Boxer Rebellion; they represent more than 100,000 Christians of China who were martyred in the reign of Empress Dowager Tz’u Hsi (Cixi).

a) Martyrs of Shanxi, killed on July 9, 1900 (known as the Taiyuan Massacre), who were Franciscan Friars Minor:

1. Saint Gregory Grassi, Bishop,

2. Saint Francis Fogolla, Bishop,

3. Saint Elias Facchini, Priest,

4. Saint Theodoric Balat, Priest,

5. Saint Andrew Bauer, Religious Brother;

b) Martyrs of Southern Hunan, who were also Franciscan Friars Minor:

6. Saint Anthony Fantosati, Bishop (martyred on July 7, 1900), vicar apostolic of Hengchow,

7. Saint Joseph Mary Gambaro, Priest (martyred on July 7, 1900), who was tortured to death,

8. Saint Cesidio Giacomantonio, Priest (martyred on July 4, 1900), burned alive.

To the martyred Franciscans of the First Order were added seven Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, of whom three were French, two Italian, one Belgian, and one Dutch:

9. Saint Mary Hermina of Jesus (in saec: Irma Grivot),

10. Saint Mary of Peace (in saec: Mary Ann Giuliani),

11. Saint Mary Clare (in saec: Clelia Nanetti),

12. Saint Mary of the Holy Birth (in saec: Joan Mary Kerguin),

13. Saint Mary of Saint Justus (in saec: Ann Moreau),

14. Saint Mary Adolfine (in saec: Ann Dierk),

15. Saint Mary Amandina (in saec: Paula Jeuris).

Of the martyrs belonging to the Franciscan family, there were also eleven Secular Franciscans, all Chinese:

15. Saint John Zhang Huan, seminarian,

16. Saint Patrick Dong Bodi, seminarian,

17. Saint John Wang Rui, seminarian,

18. Saint Philip Zhang Zhihe, seminarian,

19. Saint John Zhang Jingguang, seminarian,

20. Saint Thomas Shen Jihe, layman and a manservant,

21. Saint Simon Qin Chunfu, lay catechist,

22. Saint Peter Wu Anbang, layman,

23. Saint Francis Zhang Rong, layman and a farmer,

24. Saint Matthew Feng De, layman and neophyte,

25. Saint Peter Zhang Banniu, layman and labourer.

To these are joined a number of Chinese lay faithful:

26. Saint James Yan Guodong, farmer,

27. Saint James Zhao Quanxin, manservant,

28. Saint Peter Wang Erman, cook.

When the uprising of the “Boxers”, which had begun in Shandong and then spread through Shanxi and Hunan, also reached South-Eastern Tcheli (currently named Hebei), which was then the Apostolic Vicariate of Xianxian, in the care of the Jesuits, the Christians killed could be counted in thousands. Among these were four French Jesuit missionaries and at least 52 Chinese lay Christians: men, women and children – the oldest of them being 79 years old, while the youngest were aged only nine years. All suffered martyrdom in the month of July 1900. Many of them were killed in the church in the village of Tchou-Kia-ho (or Zhujiahe), in which they were taking refuge and where they were in prayer together with the first two of the missionaries listed below:

29. Saint Leo Mangin, S.J., Priest,

30. Saint Paul Denn, S.J., Priest,

31. Saint Rémy Isoré, S.J., Priest,

32. Saint Modeste Andlauer, S.J., Priest.

The names and ages of the Chinese lay Christians were as follows:

33. Saint Mary Zhu born Wu, aged about 50 years,

34. Saint Petrus Zhu Rixin, aged 19,

35. Saint Ioannes Baptista Zhu Wurui, aged 17,

36. Saint Mary Fu Guilin, aged 37,

37. Saint Barbara Cui born Lian, aged 51,

38. Saint Joseph Ma Taishun, aged 60,

39. Saint Lucia Wang Cheng, aged 18,

40. Saint Maria Fan Kun, aged 16,

41. Saint Mary Qi Yu, aged 15,

42. Saint Maria Zheng Xu, aged 11 years,

43. Saint Mary Du born Zhao, aged 51,

44. Saint Magdalene Du Fengju, aged 19,

45. Saint Mary Du born Tian, aged 42,

46. Saint Paul Wu Anju, aged 62,

47. Saint Ioannes Baptista Wu Mantang, aged 17,

48. Saint Paulus Wu Wanshu, aged 16,

49. Saint Raymond Li Quanzhen, aged 59,

50. Saint Peter Li Quanhui, aged 63,

51. Saint Peter Zhao Mingzhen, aged 61,

52. Saint John Baptist Zhao Mingxi, aged 56,

53. Saint Teresa Chen Jinjie, aged 25,

54. Saint Rose Chen Aijie, aged 22,

55. Saint Peter Wang Zuolong, aged 58,

56. Saint Mary Guo born Li, aged 65,

57. Saint Joan Wu Wenyin, aged 50,

58. Saint Zhang Huailu, aged 57,

59. Saint Mark Ji Tianxiang, aged 66,

60. Saint Ann An born Xin, aged 72,

61. Saint Mary An born Guo, aged 64,

62. Saint Ann An born Jiao, aged 26,

63. Saint Mary An Linghua, aged 29,

64. Saint Paul Liu Jinde, aged 79,

65. Saint Joseph Wang Kuiju, aged 37,

66. Saint John Wang Kuixin, aged 25,

67. Saint Teresa Zhang born He, aged 36,

68. Saint Lang born Yang, aged 29,

69. Saint Paulus Lang Fu, aged 9,

70. Saint Elizabeth Qin born Bian, aged 54,

71. Saint Simon Qin Chunfu, aged 14,

72. Saint Peter Liu Ziyu, aged 57,

73. Saint Anna Wang, aged 14,

74. Saint Joseph Wang Yumei, aged 68,

75. Saint Lucy Wang born Wang, aged 31,

76. Saint Andreas Wang Tianqing, aged 9,

77. Saint Mary Wang born Li, aged 49,

78. Saint Chi Zhuzi, aged 18,

79. Saint Mary Zhao born Guo, aged 60,

80. Saint Rose Zhao, aged 22,

81. Saint Maria Zhao, aged 17,

82. Saint Joseph Yuan Gengyin, aged 47,

83. Saint Paul Ge Tingzhu, aged 61,

84. Saint Rose Fan Hui, aged 45.

Besides all those already mentioned who were killed by the Boxers, it is necessary also to remember:

85. Saint Alberic Crescitelli, a priest of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions of Milan, who carried out his ministry in Southern Shaanxi and was martyred on July 21, 1900.

Some years later, members of the Salesian Society of St John Bosco were added to the considerable number of martyrs recorded above:

86. Saint Louis Versiglia, Bishop,

87. Saint Callistus Caravario, Priest.

They were killed together on February 25, 1930 at Li-Thau-Tseul.

A 14-year-old Chinese girl named Ann Wang, who was killed during the Boxer Rebellion when she refused to apostatize. She bravely withstood the threats of her torturers, and just as she was about to be beheaded, she radiantly declared, “The door of heaven is open to all” and repeated the name of Jesus three times.

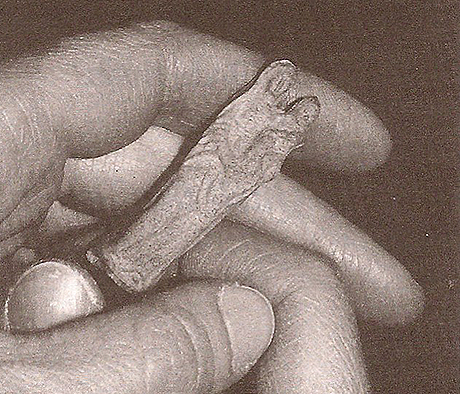

Another of the martyrs was 18-year-old Chi Zhuzi, who had been preparing to receive the sacrament of Baptism when he was caught on the road one night and ordered to worship idols. He refused to do so, revealing his belief in Christ. His right arm was cut off and he was tortured, but he would not deny his faith. Rather, he fearlessly pronounced to his captors, before being flayed alive, “Every piece of my flesh, every drop of my blood will tell you that I am Christian.”

Following the failure of the Boxer rebellion, the government recognized it had no choice but to modernize, which in turn led to a booming conversion period in the following decades. The Chinese developed respect for the moral level that Christians maintained in their hospital and schools. The continuing association between western imperialism in China and missionary efforts nevertheless continued to fuel hostilities against missions and Christianity in China. All missions were banned in China by the new communist regime after the outbreak of the Korean war in 1950, and officially continue to be legally outlawed to the present.

“The tyrant dies and his rule is over, the martyr dies and his rule begins.” – Soren Kierkegaard

Love,

Matthew