-Fra Filippo Lippi, Mystical Nativity or The Adoration in the Forest, c. 1459. Oil on a poplar panel, and the painted surface measures 127 x 116 cm, with the panel being 129.5 x 118.5 cm, originally an altarpiece for the Magi Chapel in the new Palazzo Medici in Florence, it is now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, with a copy by another artist now hanging in the chapel. Please click on the image for greater detail.

-by Br Daniel Benedict Rowlands, OP, English Province

“All three comings of Christ described by St Bernard seem to be represented in this painting, but especially the intermediate coming of Christ to the individual soul: in the shadowy forest of the human heart, shrouded in the gloom of sin, it remains within our capability to clear a small glade into which Christ may come to dwell.

One could be forgiven for thinking that the scene before us is nothing more than a variation on a traditional nativity, with the two protagonists abstracted from their familiar setting, and placed instead in a rather forbidding forest. Indeed, the Adoration of the Christ Child motif, in which an intense focus is placed on the blessed Mother’s adoration of her son, began to appear following the mystic St Bridget of Sweden’s vision of the nativity in the 14th century. Nevertheless, I suggest that we need not wait until Christmas to enjoy this painting, for there is much that commends it as apt stimulus for Advent meditation.

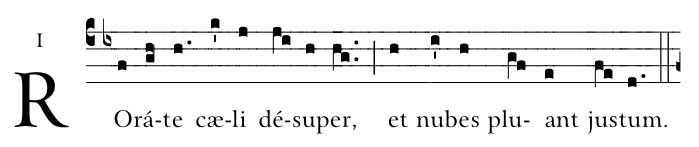

The Office of Readings on the Thursday of the first week of Advent features the following passage in which St Bernard speaks of the threefold coming of Christ:

“In the first coming the Lord was seen on earth and lived among men… In His last coming all flesh shall see the salvation of our God, and they shall look on Him whom they have pierced. The other coming is hidden. In it, only the chosen see Him within themselves… Listen to Christ Himself, If a man loves Me he will keep My words, and My Father will love Him, and We will come to him… Where, then, are they to be kept? Without any doubt they are to be kept in the heart… Let it pierce deep into your inmost soul and penetrate your feelings and actions… If you keep the word of God in this way without a doubt you will be kept by It.”

I think this painting can naturally be read as depicting the intermediate coming described by St Bernard. In the shadowy, stony forest of the human heart, shrouded in the gloom of sin, it remains within our capability to clear a small glade into which Christ may come to dwell with us. Lippi’s depiction of the forest is probably based on the woods of Camaldoli, which makes St Romuald – the founder of the Camaldolese Order – the likely identity of the monk in the background. Cutting down trees for timber was the monks’ primary source of manual labour, so the fusion of prayer and work enjoined by the Rule of St Benedict seems to take on a special significance here: the lofty pines of pride are what stand most in need of felling. Fra Lippi is thoughtful enough to offer us an axe with which we too may take up this work: we seem to be invited to imitate the Israelites who undertook the humble task of sourcing the cedar for Solomon’s temple. As for overlaying the sanctuary with pure gold, we find that work already done – quite literally thanks to the artist – in the person of our Lady, the Domus Aurea (House of Gold) as she is called in the Litany (cf. 1 Kings 5-6).

Within this “interior forest” in which time and space are transcended, the first and final comings are also allusively juxtaposed. I have no qualms putting into the mouth of a youthful John the Baptist, who stands next to the newborn Christ child, the words of his later proclamation: “Even now the axe is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire” (Mat. 3:10). In the same act by which we prepare ourselves to contemplate the great mystery of the incarnation and so bring Christ to birth within us, we concomitantly prepare ourselves to be judged by Him.

Looking at this Florentine Renaissance masterpiece with an eye to eschatology, I can’t help but call to mind the work of another of the city’s masters, namely Dante and the evocative opening tercet of the Inferno: “Midway along the journey of our life I woke to find myself in a dark wood, for I had wandered off from the straight path”. Bewildered by ignorance and sin, the pilgrim does not, like Dante, negotiate a bestial trinity of vices (embodied by the leopard, lion, and wolf) with only the assistance of natural reason (represented by Virgil). Rather, having prepared the garden of the soul, Lippi’s contemplative has been graced with the condescension of the Logos Himself, and through Him, now experiences a foretaste of participation in the Trinitarian life itself. Manifestations of the Trinity are certainly not a common theme in Advent art, whether it be of incarnational or eschatological emphasis. St Bernard’s intermediate coming of Christ to the soul, however, does provide a fitting context in which the the veil of human nature assumed by the second person of the Trinity may indeed take on a particularly striking transparency. Perhaps, if I am granted some interpretative licence, Lippi is alluding to this with the exquisitely diaphanous drapery that clothes the lower half of the Divine Infant.

I will end with a prayer of praise contained in the Advent Lyrics – a collection of Anglo-Saxon poetry that I mention in an upcoming post – which also takes up this theme of recognising the mystery of the incarnation as the common work of the whole Godhead:

“O beautiful, plenteous in honours,

high and holy, heavenly Trinity

blessed far abroad across the spacious plains,

Whom, by right, speech-bearers,

wretched earth-dwellers, should supremely praise

with all their power, now God, true to His pledge,

has revealed a Saviour to us, that we may know Him.”

Love & the joy only He can bring,

Matthew