“I really wish I could believe, because you (Catholics) have the coolest s***!”, so blogged a respondent in reply to a page displaying the mummified head of St Catherine of Siena. (She was so popular different pieces of her relics are scattered throughout Italy.)

I must say, the relics of St Catherine of Bolgna, OSC, lead the category, at least what I can tell from the web.

Catherine Vigri was born and died in Bologna but spent most of her life in Ferrara. She was raised at the court of Nicholas III d’Este, Marquis of Ferrara, whom her father served as a diplomatic agent. Ferrara had spent much of the preceding century defending itself from Milan and Venice, so a period of relative peace allowed the Este family to do what the other northern courts were doing: trying to compete with Florence as a cultural center.

In this environment Catherine apparently received a humanist education; we know that she learned Latin, music, and the art of manuscript illumination. She was educated with Margaret d’Este, Nicholas’ daughter, and was one of her attendants until 1427, when Margaret was married to Roberto Malatesta. After Margaret’s marriage and the death of her own father, Catherine joined a community of about 15 lay women in Ferrara. The women wished to join one of the established religious orders but disagreed as to which.

Twenty years earlier a Frenchwoman, St Colette of Corbie, of prior note, had established a reformed branch of the Poor Clares, the order that had been founded by Clare of Assisi 200 years earlier but that had, over the years, grown far away from Clare’s vision. Word of Colette’s reform had spread to Italy, and Catherine and some (but only some) of the other women in her group wished to join the Reformed Poor Clares.

The disagreement among the women was severe: first, in 1431, the bishop briefly disbanded the entire group; a year later, Catherine and some of the others were professed as Poor Clares, although not according to the reformed Rule; then in 1434, 14 nuns, including Catherine, were absolved by the pope of unspecified crimes involving “apostasy.” It wasn’t until the following year that the new monastery was officially allowed to follow Colette’s reformed Rule.

During her years in Ferrara, Catherine acted as mistress of novices, and it was in this capacity that she began to write “Le sette armi spiritual” (The seven spiritual weapons). By 1450 the Ferrara monastery had grown to include 85 women, and in 1456 Catherine was sent to found a new house in Bologna, Corpus Domini. There she became abbess and stayed until her death. Before she died, she gave her nuns her manuscript to be read by them and to be shared with the nuns at Ferrara. Le sette armi spirituali was printed by the Bolognese nuns in 1475 (one of the earliest printed works in that city) and was frequently reprinted during the 1500s.

Some of Catherine’s other works, as well as her hymns (laudi) and letters, have been published but not yet translated. Among these are I dodici giardini (The twelve gardens), on the stages of growth in love of God; Rosarium metricum (a Latin poem); and I Sermoni (a collection of sermons that Catherine gave to her nuns at Corpus Domini in Bologna). Six years after Catherine’s death, her secretary, Illuminata Bembo, wrote Catherine’s biography, Specchio di illuminazione (Mirror of illumination), which includes the words of as well as anecdotes about the abbess.

Catherine also produced frescoes, free-standing paintings, and illuminated manuscripts; the frescoes are gone, but some of her other art has survived. When art scholars write of her work, they usually use her family name, Caterina Vigri.

Le sette armi spirituali seems to be almost two separate documents. The first six chapters and the start of the seventh are very practical and down-to-earth, intended for newcomers to the religious life. This part is brief, the organization is clear and easy to follow, and the dominant image is that of the almost constant warfare familiar to the courtier families from which her novices had come.

The rest of the long Chapter 7 and Chapters 8-10 describe Catherine’s visionary experiences and her attempts to make sense of them. Like Chapters 1-6 they are addressed to the novices, but content and structure are quite different. For the modern reader, the last chapters are perhaps the most interesting because of what they reveal of Catherine’s internal conflict.

Graced with many heavenly visions and mystical experiences, on Christmas Eve in 1445, the Blessed Mother gave Catherine the Infant Jesus to hold. Catherine wrote of this experience, “The perfume that emanated from His Pure Flesh was so sweet that there is neither tongue that can express, nor such a keen mind imagine, the very beautiful and delicate Face of the Son of God, when one could say all that was to be said, it would be nothing.” Catherine was not alone in experiencing this most wondrous event as her fellow Sisters smelled the holy Presence of the baby Jesus and our Lady as a heavenly fragrance filled the room. Another time Jesus spoke to her from the crucifix in her room.

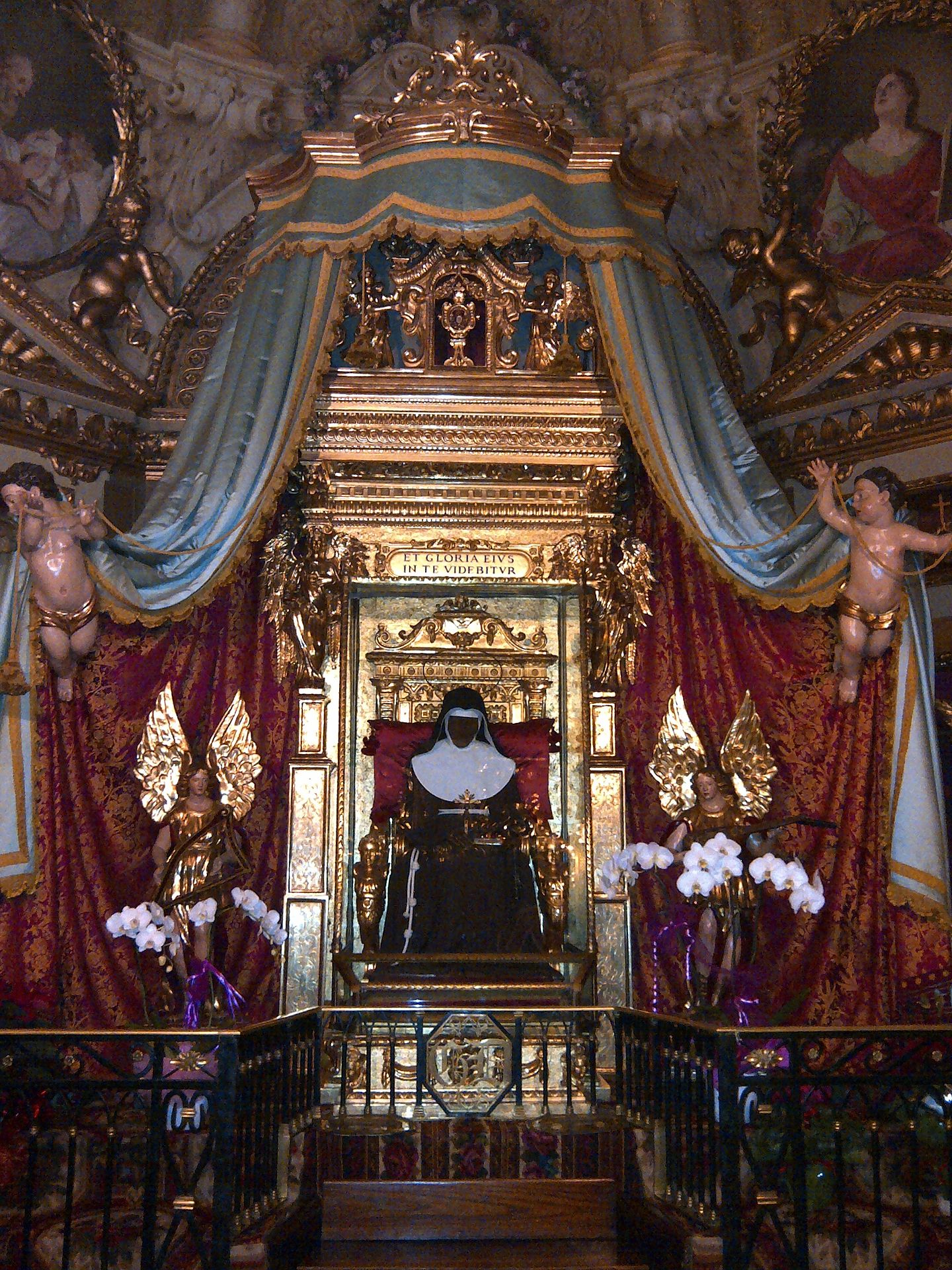

In Lent of 1463, Catherine became seriously ill, and died on March 9th. Buried without a coffin, her body was exhumed eighteen days later because of cures attributed to her and also because of the sweet scent coming from her grave. Her body was later enshrined in the chapel. The flesh is grown dark, but that may well have been because of the heat and soot of candles that were burned for years around her exposed remains. She is seated in response to a request of hers to a sister she appeared to in a vision in 1500.

“Whoever wishes to carry the cross for His sake, must take up the proper weapons for the contest, especially those mentioned here. First, diligence; second, distrust of self; third, confidence in God; fourth, remembrance of Passion; fifth, mindfulness of one’s own death; sixth, remembrance of God’s glory; seventh, the injunctions of Sacred Scripture following the example of Jesus Christ in the desert.” – Saint Catherine of Bologna, from On the Seven Spiritual Weapons

“Without a doubt, obedience is more meritorious than any other penance. And what greater penance can there be than keeping one’s will continually submissive and obedient?”

–St. Catherine of Bologna

Prayer

Dear saintly Poor Clare, so rich in love for Jesus and Mary, you were endowed with great talents by God and you left us most inspiring writings and paintings of wondrous beauty. You were chosen as Abbess in the monastery of Poor Clares at Bologna. You did all for God’s greater glory and in this you are a model for all. Make artists learn lessons from you and use their talents to the full. Amen.

Love,

Matthew