-by Martin Bouche, print, published 1683, Bl John Gavan, SJ, please click on the image for greater detail

John Gavan, aliàs Gawen, was born in London in 1640, to a family which originally came from Norrington in Wiltshire, England. He was educated at the Jesuit College at St. Omer’s and then at Liège and Watten. He began his priestly office in 1670 in Staffordshire, a county which was one of the strongholds of the Roman Catholic faith in England. He had an affectionate nickname “the Angel”.

Boscobel House – Gavan’s presence here in August 1678 would later have fatal consequences. please click on the image for greater detail.

On the Feast of the Assumption, 15 August 1678, he took his final vows to the Society of Jesus at Boscobel House, the home of the Penderel family, who were famous for sheltering Charles II after he fled from his defeat at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. Among the witnesses were two other martyrs of the Popish Plot, William Ireland and Richard Gerard of Hilderstone. The ceremony was followed by dinner, and the guests then viewed the Royal Oak, the tree in which the King had hidden after fleeing from Worcester.

This celebration would have fatal consequences for Gavan (and also for two others who were present, William Ireland and Richard Gerard) during the Popish Plot, when Stephen Dugdale, one of the principal informers associated with the Plot, learned of it and accused the party of having gathered at Boscobel in order to plan a conspiracy to kill the King. Until January 1679, Gavan escaped arrest because Titus Oates, who had invented the Plot about a month after Gavan took his vows, did not know him. On receiving Dugdale’s testimony the Government issued a reward for Gavan’s arrest on 15 January.

Gavan fled to London and took refuge at the Imperial Embassy. Arrangements were made to smuggle him out of England; but a spy called Schibber denounced him and he was arrested on 29 January. The ambassador did not claim diplomatic immunity for Gavan, although the Embassies of the Catholic powers, taking their lead from the Spanish ambassador, did claim immunity for other priests, including George Travers. The reason for the ambassador surrendering Gavan was apparently that he was arrested in the Embassy stables, and was thus technically outside the precincts of the Embassy itself when he was taken.

Gavan was tried on 13 June 1679 with Thomas Whitbread, John Fenwick, William Barrow and Anthony Turner. A bench of seven judges tried them, headed by the Lord Chief Justice, Sir William Scroggs, a firm believer in the Plot, and deeply hostile to Catholic priests in general. Gavan, who acted as the spokesman for all the five accused, mounted a spirited defence, which led a modern historian to call him one of the ablest priests of his generation. Attempts by Roman Catholic witnesses to prove that Titus Oates had been at St Omer’s on crucial dates when he claimed to be in London failed, as the judges gave a ruling that Catholic witnesses could receive a papal dispensation to lie on oath, and were, therefore, less credible than Protestants. Gavan had far greater success exposing the inconsistencies in Oates’ own testimony: in particular, Oates could not explain why he had not denounced Gavan in September 1678 when he first made his accusations against Whitbread and Fenwick. Gavan concluded his defence with a long and eloquent plea of innocence, despite constant interruption from Scroggs.

Scroggs, in his summing-up to the jury, admitted that he has already forgotten much of the evidence (judges then did not take notes, apparently because they had no desks to write on) but made it clear to the jury that he expected a guilty verdict, which the jury duly brought in after fifteen minutes. The five were sentenced to death the next day.

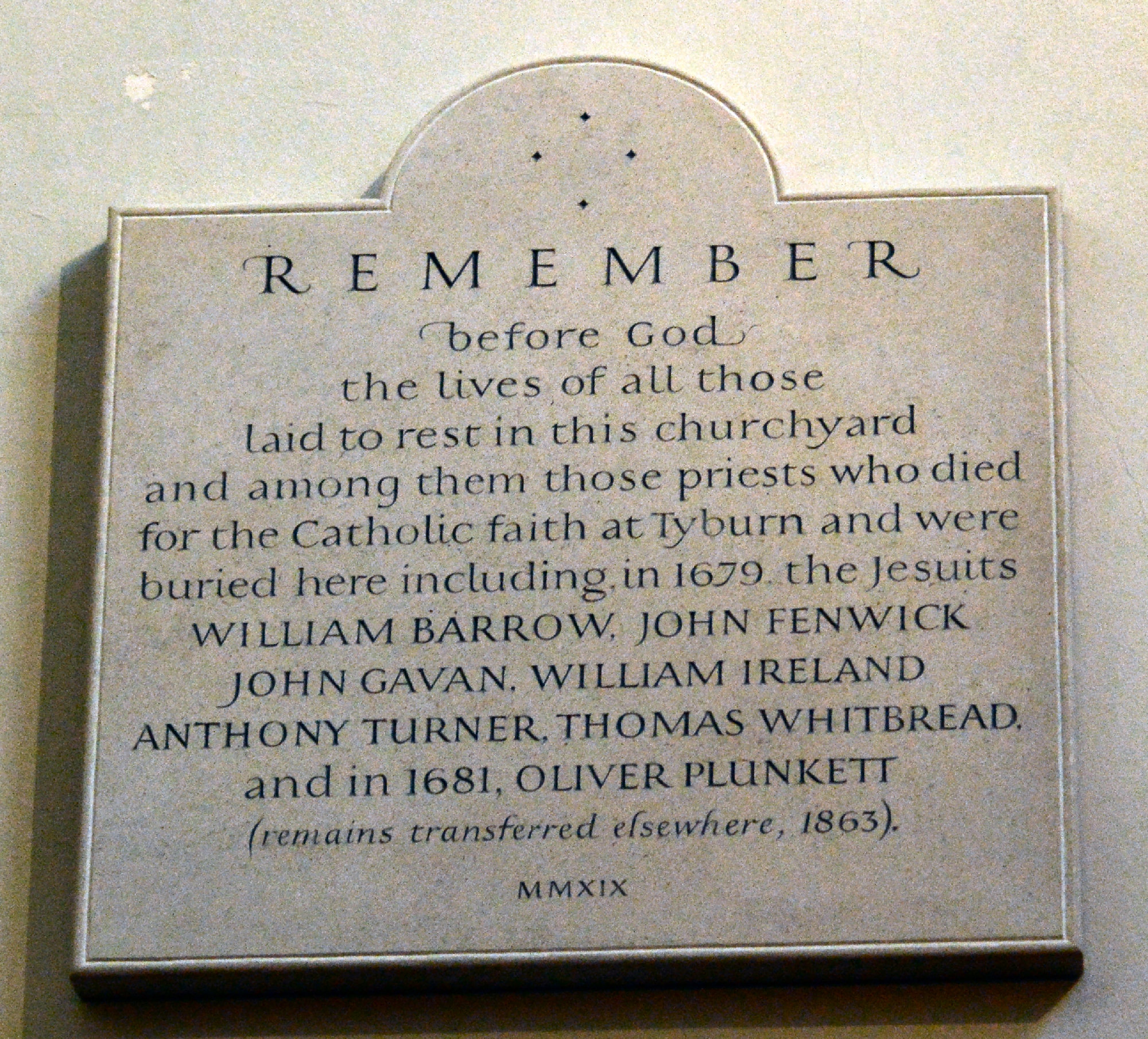

They were hanged at Tyburn on 20 June 1679. The behaviour of the crowd suggests strongly that public opinion was turning in favour of the victims. According to witnesses, the onlookers stood in perfect silence for at least an hour while each of the condemned men made a last speech maintaining his innocence; finally, Gavan led all five condemned men in an act of contrition. His own last words were reported to have been “I am content to undergo an ignominious death for the love of you, dear Jesus”. As an act of clemency, King Charles II (who was convinced of their innocence, but believed that he could not risk inflaming public opinion by issuing a royal pardon) gave orders that they should be allowed to hang until they were dead, and thus be spared the usual horrors of drawing and quartering. They were buried in the churchyard of St. Giles in the Fields.

“Dearly beloved Country-men, I am come now to the last Scene of Mortality, to the hour of my Death, an hour which is the Horizon between Time and Eternity, an hour which must either make me a Star to shine for ever in the Empyreum above, or a Firebrand to burn everlastingly amongst the damned Souls in Hell below; an hour in which if I deal sincerely, and with a hearty sorrow acknowledge my crimes, I may hope for mercy; but if I falsly deny them, I must expect nothing but Eternal Damnation; and therefore what I shall say in this great hour, I hope you will believe. And now in this hour I do solemnly swear, protest, and vow, by all that is Sacred in Heaven and on Earth, and as I hope to see the Face of God in Glory, that I am as innocent as the Child unborn of those treasonable Crimes, which Mr. Oates and Mr. Dugdale have Sworn against me in my Tryal, and for which, sentence of Death was pronounced against me the day after my Tryal; and that you may be assured that what I say is true, I do in the like manner protest, vow, and swear, as I hope to see the Face of God in Glory, that I do not in what I say unto you, make use of any Equivocation, mental Reservation, and material Prolocution, or any such ways to palliate Truth. Neither do I make use of any dispensations from the Pope, or any body else; or of any Oath of secresie, or any absolution in Confession or out of Confession to deny the truth, but I speak in the plain sence which the words bear; and if I do not speak in the plain sence which the words bear, or if I do speak in any other terms to palliate, hide, or deny the truth, I wish with all my Soul that God may exclude me from his Heavenly Glory, and condemn me to the lowest place of Hell Fire: and so much to that point.

And now, dear Country-men, in the second place, I do confess and own to the whole World that I am a Roman Catholick, and a Priest, and one of that sort of Priests which you call Jesuits; and now because they are so falsly charged for holding King-killing Doctrine, I think it my duty to protest to you with my last dying words, that neither I in particular, nor the Jesuits in general, hold any such opinion, but utterly abhor and detest it; and I assure you, that among the multitude of Authors, which among the Jesuits have printed Philosophy, Divinity, Cases or Sermons, there is not one to the best of my knowledge that allows of King-killing Doctrine, or holds this position, That it is lawful for a private person to kill a King, although an Heretick, although a Pagan, although a Tyrant, there is, I say, not one Jesuit that holds this, except Ma∣riana, the Spanish Jesuit, and he defends it not absolutely, but only problematically, for which his Book was called in again, and the opinions expugned and sentenced. And is it not a sad thing, that for the rashness of one single Man, whilst the rest cry out against him, and hold the contrary, that a whole Religious Order should be sentenc’d? But I have not time to discuss this point at large, and therefore I refer you all to a Royal Author, I mean the wife and victorious King Henry the Fourth of France, the Royal Grandfather of our present gracious King, in a publick Oration which he pronounced himself in defence of the Jesuits, said, that he was very well satisfied with the Jesuits Doctrine concerning Kings, as believing conformable to what the best Doctors of the Church have taught. But why do I relate the testimony of one particular Prince, when the whole Catholick World is the Jesuit’s Advocate? for to them chiefly Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and Flanders, trust the Education of their Youth, and to them in a great proportion, they trust their own Souls to be governed in the Sacraments. And can you imagin so many great Kings and Princes, and so many wise States should do or permit this to be done in their Kingdoms, if the Jesuits were men of such damnable principles as they are now taken for in England?

In the third place, dear Country-men, I do attest, that as I never in my life did machine, or contrive either the deposition or death of the King, so now I do heartily desire of God to grant him a quiet and happy Reign upon Earth, and an Everlasting Crown in Heaven. For the Judges also, and the Jury, and all those that were any ways concern’d, either in my Tryal, Accusation, or Condemnation, I do humbly ask of God, both Temporal and Eternal happiness. And as for Mr. Oates and Mr. Dugdale, whom I call God to witness, by false Oaths have brought me to this untimely end, I heartily forgive them, because God commands me so to do; and I beg of God for his infinite Mercy to grant them true Sorrow and Repentance in this World, that they be capable of Eternal happiness in the next. And so having discharged my Duty towards my self, and my own Innocence towards my Order, and its Doctrine to my Neighbour and the World, I have nothing else to do now, my great God, but to cast my self into the Arms of your Mercy, as firmly as I judge that I my self am, as certainly as I believe you are One Divine Essence and Three Divine Persons, and in the Second Person of your Trinity you became Man to redeem me; I also believe you are an Eternal Rewarder of Good, and Chastiser of Bad. In fine, I believe all you have reveal’d for your own infinite Veracity; I hope in you above all things, for your infinite Fidelity; and I love you above all things, for your infinite Beauty and Goodness; and I am heartily sorry that ever I offended so great a God with my whole heart: I am contented to undergo an ignominious Death for the love of you, my dear Jesu, seeing You have been pleased to undergo an ignominious Death for the love of me.”

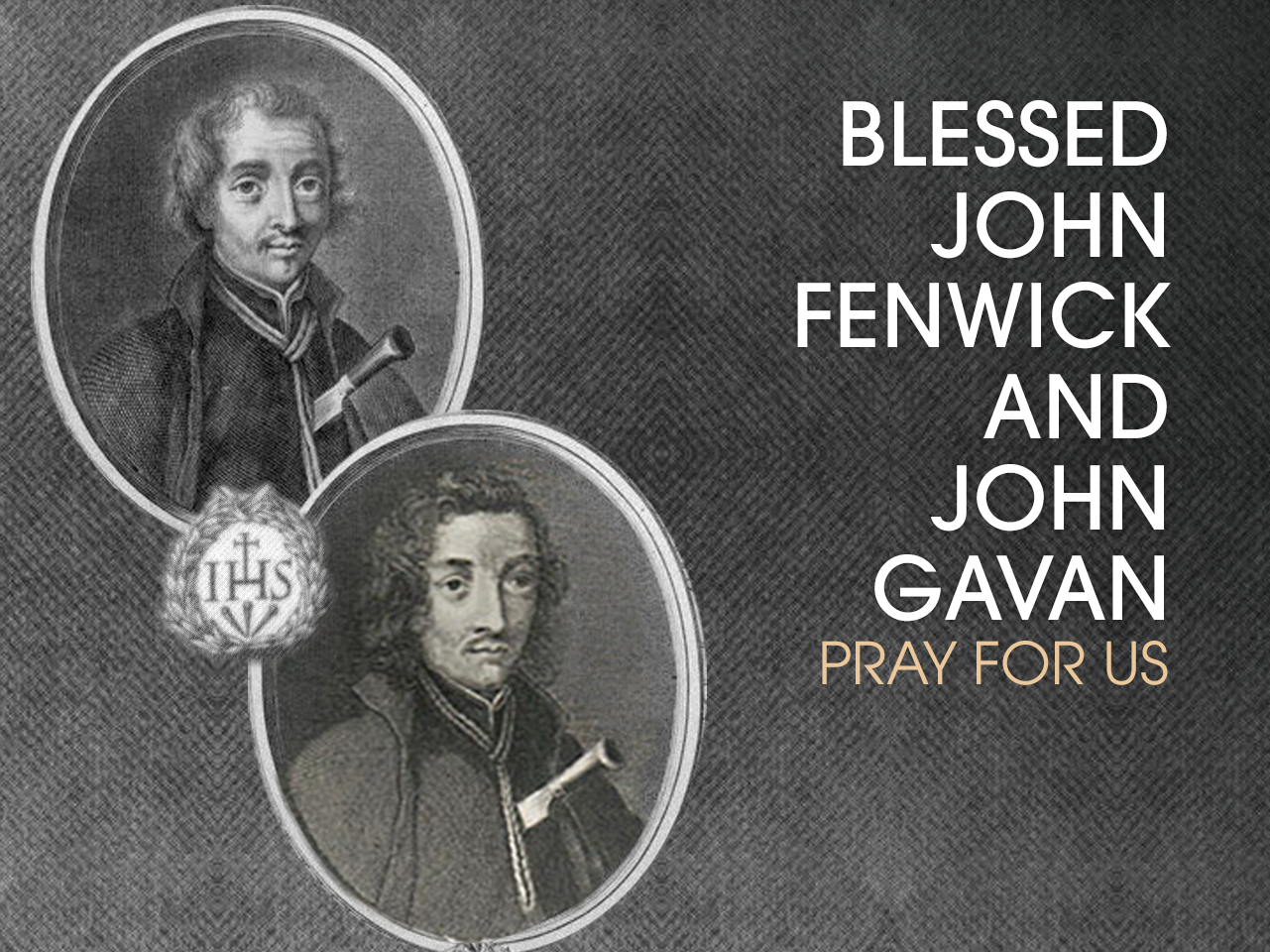

-by Martin Bouche, print, published 1683, Bl John Fenwick, SJ

-by Martin Bouche, print, published 1683, Bl John Fenwick, SJ

John Fenwick, whose real surname was Caldwell, was born in county Durham, of Protestant parents who disowned him when he became a Roman Catholic convert. He took his course in humanities at the College of St. Omer, was sent to Liège to study theology, and entered the Society of Jesus at Watten on 28 September 1660. Having completed his studies, he was ordained a priest, and spent several years, from 1662, as procurator or agent at the College of St. Omer. He was made a professed father in 1676, and was sent to England the same year.

He resided in London as procurator of St. Omer’s College, and was also one of the missionary fathers there. In 1678, on the information of Titus Oates, he was summoned to appear before the Privy Council, and committed to Newgate Prison. He was put in chains and suffered great pain as a result: one of his legs became so infected that amputation was proposed. His correspondence was seized, but to the Crown’s disappointment it turned out to be completely innocuous: as he forcefully pointed out at his second trial, among at least a thousand letters taken from him there was not one which could be construed as treasonable. He was tried for high treason with William Ireland, in that they had conspired to kill King Charles II, a charge fabricated by Oates and later embellished by other informers. Oates claimed that he had overheard some incriminating remarks they made at a meeting of senior Jesuits in late April 1678 in the White Horse Tavern on the Strand: they could truthfully deny this, although they had at the time been at a meeting of senior Jesuits in the Palace of Whitehall. As the evidence of treason was insufficient, since the Crown lacked the requisite two witnesses, he was remanded back to prison.

However, in the political climate of the time, it was unthinkable that so prominent a Jesuit should be allowed to escape with his life: accordingly, he was arraigned a second time at the Old Bailey on 13 June 1679, before all the High Court judges. He was tried together with four other Jesuit fathers (John Gavan, William Harcourt, Thomas Whitebread and Anthony Turner}. Oates and two other notorious informers, William Bedloe and Stephen Dugdale, were the main witnesses against them, and in accordance with the direction of Lord Chief Justice William Scroggs, the jury found the prisoners guilty, despite their spirited defence. At the end of the prosecution case Fenwick made a vigorous protest:

“I have had a thousand letters taken from me: not any of these letters had anything of treason in them. All the evidence comes but to this: there is but saying and swearing.”

The five Jesuits suffered death at Tyburn on 20 June 1679. As an act of clemency, the King, who was well aware that they were innocent, but realised that it would be politically unthinkable to grant a royal pardon or reprieve, ordered that they be allowed to hang until they were dead, and be spared the indignity of drawing and quartering. In a sign that public sympathy was turning against the plot, the large crowd heard their final speeches from the scaffold in respectful silence, as each maintained his innocence. Fenwick’s remains were buried in the churchyard of St. Giles-in-the-Fields.

An account of the trial and condemnation of the five Jesuits for High Treason, in conspiring the Death of the King, the Subversion of the Government and Protestant Religion was published by authority at London, 1679.

“Good People, I suppose you expect I should say something as to the Crime I am Condemned for, and either acknowledge my Guilt, or assert my Innocency; I do therefore declare before God and the whole World, and call God to witness that what I say is true, that I am innocent of what is laid to my Charge of Plotting the King’s Death, and endeavoring to subvert the Government, and bring in a foreign Power, as the Child unborn; and that I know nothing of it, but what I have learn’d from Mr. Oates and his Companions, and what comes originally from them. And to what is said and commonly believed of Roman Catholicks, that they are not to be believed or trusted, because they can have Dispensations for Lying, Perjury, killing Kings, and other the most enormous Crimes; I do utterly renounce all such Pardons, Dispensations, and withall declare, That it is a most wicked and malicious Calumny cast on them, who do all with all their hearts and souls hate and detest all such wicked and damnable Practises, and in the words of a dying Man, and as I hope for Mercy at the hands of God, before whom I must shortly appear and give an account of all my actions, I do again declare, That what I have said is most true, and I hope Christian Charity will not let you think, that by the last act of my Life, I would cast away my Soul, by sealing up my last Breath with a damnable Lye.”

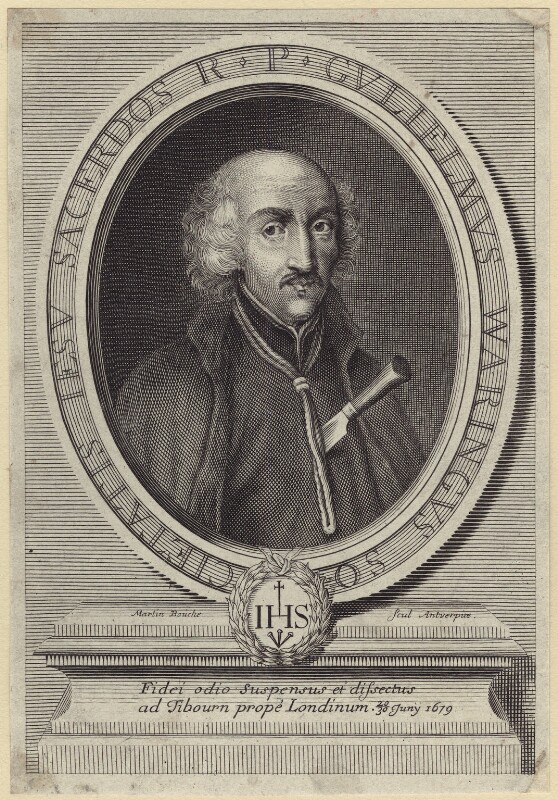

-by Martin Bouche, print, 1683, Bl Thomas White, SJ

Thomas White, alias Harcourt, alias Whitbread/Whitebread was a native of Essex, but little is known of his family or early life. He was educated at St. Omer’s, and entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus on 7 September 1635. Coming upon the English mission in 1647, he worked in England for more than thirty years, mostly in the eastern counties. On 8 December 1652, he was professed of the four vows. Twice he was superior of the Suffolk District, once of the Lincolnshire District, and finally, in 1678 he was declared Provincial. In this capacity he refused to admit Titus Oates as a member of the Society, on the grounds of his ignorance, blasphemy and sexual attraction to young boys, and expelled him forthwith from the seminary of St Omer; shortly afterwards Titus, motivated by personal spite against Whitbread, and against the Jesuits generally, fabricated the so-called “Popish Plot”.

It was said later that Whitbread had a miraculous presentiment of the plot, and undoubtedly he preached a celebrated sermon at Liège in July 1678, on the text “Can ye drink of the cup that I drink of?”, in which he warned his listeners that the present time of tranquillity would not last, and that they must be willing to suffer false accusations, imprisonment, torture and martyrdom. Having completed a tour of his Flanders province, he went to England but at once fell ill with plague.

Whitbread was arrested in London on Michaelmas Day (i.e., 29 September) 1678, but was so ill that he could not be moved to Newgate until three months later. The house in which he and his secretary Fr. Edward Mico (who died in Newgate shortly afterwards) had been lodging was part of the Spanish Embassy in Wild Street, but for whatever reason, there was no claim of diplomatic immunity, as there was in the case of some other priests. He was first indicted at the Old Bailey, on 17 December 1678, but the evidence against him and his companions broke down. Oates testified that he had overheard Whitbread and other senior Jesuits plotting to kill the King in late April 1678 in the White Horse Tavern in the Strand. This was probably garbled second-hand information about an actual Jesuit meeting which was then going on at Whitehall Palace: but no one corroborated Oates’ story, and Whitbread could in good conscience deny the assassination plot, and that he had ever been in the White Horse Tavern.

Given the state of public opinion, it was unthinkable to the Government that Whitbread, whom Oates and the other informers had identified as one of the originators of the Plot, should be allowed to escape punishment. Accordingly he was remanded and kept in prison until 13 June 1679, when he was again indicted for treason, and with four others was found guilty on the perjured evidence of Oates, William Bedloe and Stephen Dugdale. The importance of the trial is shown by the fact that it was heard by a bench of seven judges, headed by the Lord Chief Justice, Sir William Scroggs, who was a firm believer in the Plot and deeply hostile to Catholic priests. In the circumstances Whitbread could not have hoped to escape, and, although he strongly maintained his innocence, Kenyon suggests that he had resigned himself to death. Certainly the sermon he had preached at Liège the previous year suggests that he expected to suffer the death of a martyr, sooner or later.

He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn. The King, who knew that he and his fellow victims were innocent, ordered that they be allowed to die before being mutilated. The well-known story that they were offered a pardon on the scaffold if they would confess seems to have no substance. The crowd showed that on this occasion its sympathies were with the victims, and it listened in respectful silence as Whitbread and the others made lengthy speeches protesting their innocence. The others executed with him were John Gavan, John Fenwick, William Harcourt and Anthony Turner. After the execution, his remains, and those of his companions, were buried in St. Giles’s in the Fields.

Whitbread wrote Devout Elevation of the Soul to God and two short poems, To Death and To His Soul, which are printed in The Remonstrance of Piety and Innocence.

“I Suppose it is expected I should speak something to the matter I am condemned for, and brought hither to suffer, it is no less than the contriving and plotting His Majesty’s Death, and the alteration of the Government of the Church and State; you all either know, or ought to know, I am to make my appearance before the Face of Almighty God, and with all imaginable certainty and evidence to receive a final Judgment, for all the thoughts, words, and actions of my whole life: So that I am not now upon terms to speak other than truth, and therefore in his most Holy Presence, and as I hope for Mercy from his Divine Majesty, I do declare to you here present, and to the whole World, that I go out of the World as innocent, and as free from any guilt of these things laid to my charge in this matter, as I came into the World from my Mother’s Womb; and that I do renounce from my heart all manner of Pardons, Absolutions, Dispensations for Swearing, as occasions or Interest may seem to re∣quire, which some have been pleased to lay to our charge as matter of our Practice and Doctrine, but is a thing so unjustifiable and unlawful, that I believe, and ever did, that no power on Earth can authorize me, or any body so to do; and for those who have so falsly accused me (as time, either in this World, or in the next, will make appear) I do heartily forgive them, and beg of God to grant them his holy Grace, that they may repent their unjust proceedings against me, otherwise they will in conclusion find they have done themselves more wrong than I have suffered from them, though that has been a great deal. I pray God bless His Majesty both Temporal and Eternal, which has been my daily Prayers for him, and is all the harm that I ever intended or imagined against him. And I do with this my last breath in the sight of God declare, that I never did learn, teach, or believe, that it is lawful upon any occasion or pretence whatsoever, to design or contrive the Death of His Majesty, or any hurt to his Person; but on the contrary, all are bound to obey, defend, and preserve his Sacred Person, to the utmost of their power. And I do moreover declare, that this is the true and plain sence of my Soul in the sight of him who knows the Secrets of my Heart, and as I hope to see his blessed Face without any Equivocation, or mental Reservation. This is all I have to say concerning the matter of my Condemnation, that which remains for me now to do, is to recommend my Soul into the hands of my blessed Redeemer, by whose only Merits and Passion I hope for Salvation.”

-by Cornelius van Merlen, print, Bl William Barrow, SJ

William Barrow (alias Waring, alias Harcourt, alias Harrison) was born in Lancashire. He made his studies at the Jesuit College, St. Omer’s, and entered the Society of Jesus at Watten in 1632. He was sent to the English mission in 1644 and worked in the London district for thirty-five years, becoming, at the beginning of 1678, its superior.

At the outbreak of the Popish Plot, Barrow was one of the most sought-after of the alleged plotters, although his use of the alias Harcourt caused the Government great confusion, as several other Jesuits also used it. He went into hiding in London, and for several months eluded capture. Finally, in May 1679, he was arrested and committed to Newgate on the charge of complicity in the plot brought against him by Titus Oates. The trial, in which he had as fellow-prisoners his colleagues, Thomas Whit(e)bread, John Fenwick, John Gavan, and Anthony Turner, commenced on 13 June 1679.

Lord Chief Justice Scroggs presided, assisted by no less than six junior judges. Oates, William Bedloe, and Stephen Dugdale were the principal witnesses for the Crown. The prisoners were charged with having conspired to kill King Charles II and subvert the Protestant religion. They defended themselves by the testimony of their own witnesses and their cross-examinations of their accusers. Oates’ claim that he had heard some of them plotting treason in the White Horse Tavern in London in late April 1678 was something they could in could conscience deny, although they did not feel obliged to mention that they had been at a meeting of the Jesuit chapter in Whitehall Palace at the time. John Gavan, the youngest and ablest of the five, bore the main burden of conducting his colleagues’ defence as well as his own.

Scroggs in directing the jury laid down two crucial legal principles-

- as the witnesses for the prosecution had recently received the royal pardon, none of their undeniable previous misdemeanours could be legally admitted as impairing the value of their testimony; and

- that no Catholic witness was to be believed, as it was to be assumed that he had received a dispensation to lie.

Barrow and the others were found guilty, and condemned to undergo the punishment for high treason. They were executed together at Tyburn, 20 June 1679. The King, who was well aware that they were innocent, ordered as an act of grace that they be spared drawing and quartering, and given proper burial. The behaviour of the crowd, which listened in respectful silence as each man maintained his innocence, suggests that popular opinion was turning against the Plot. They were buried in St Giles in the Fields.

By a papal decree of 4 December 1886, this martyr’s cause was introduced, but under the name of “William Harcourt”. This is the official name of beatification.

“The words of dying persons have been always esteem’d as of greatest Authority, be∣cause uttered then, when shortly after they were to be cited before the high Tribunal of Almighty God, this gives me hopes that mine may be look’d upon as such, therefore I do here declare in the presence of Almighty God, and the whole Court of Heaven, and this numerous Assembly, that as I ever hope (by the Merits and Passion of my sweet Saviour Jesus Christ) for Eternal Bliss, I am as innocent as the Child unborn of any thing laid to my charge, and for which I am here to dye, and I do utterly abhor and detest that abominable false Doctrine laid to our charge, that we can have Licenses to commit perjury, or any Sin to advantage our cause, being expresly against the Doctrine of St. Paul, saying, Non sunt faci∣enda mala, ut eveniant bona; Evil is not to be done that good may come thereof. And therefore we hold it in all cases unlawful to kill or murder any person whatsoever, much more our law∣ful King now Reigning, whose personal and temporal Dominions we are ready to defend against any Opponent whatsoever, none excepted. I forgive all that have contriv’d my Death, and humbly beg pardon of Almighty God. I also pardon all the World. I pray God bless His Majesty, and grant him a prosperous Reign. The like I wish to his Royal Con∣sort the best of Queens. I humbly beg the Prayers of all those of the Roman Church, if any such be present.”

-by Cornelius van Merlen, print, Bl Anthony Turner, SJ

Anthony Turner was born in Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, the son of a clergyman, Toby Turner, who was Rector of Little Dalby and Elizabeth, nee Cheseldine. He went to Uppingham School in Rutland, then studied at Peterhouse, Cambridge, where, according to tradition, he converted to Roman Catholicism.

He went to the English College, Rome in October 1650 and then to the Jesuit College, St Omer. He was ordained there on 12 April 1659.

In 1661, he was sent to run the Jesuits’ Worcestershire mission, and he remained there for the rest of his ministry; in due course, he was appointed Jesuit Superior for the District (1670-78).

At the outbreak of the Popish Plot, the Government showed exceptional interest in apprehending Turner. Why he was considered to be of such importance is unclear, but he must have been thought well worth catching, as pursuivants searched for him in three counties.

Turner resolved to suffer for the Church but was urged to flee England by his superiors. He journeyed to London in January 1679 to take refuge in the embassy of one of the Catholic powers and to find a Jesuit who could get him out of the country; his search was unsuccessful and he gave the last of his money to a beggar and turned himself in to the authorities in February 1679.

His motives for doing this are unclear: Jesuits, though were schooled to endure martyrdom where necessary, were not expected to actively seek it, nor does his spirited defence at his trial suggest that he had any such wish. It is most likely, as J. P. Kenyon suggests, that his physical and mental suffering had caused him to suffer a short-lived nervous breakdown.

Although Turner was not on Titus Oates’ list, he was moved to Newgate Prison and tried on 13 June 1679 together with Thomas Whitbread, John Fenwick, John Gavan and William Barrow. No fewer than seven judges sat on the court that tried them, headed by the Lord Chief Justice, Sir William Scroggs, who was a convinced believer in the Plot and cherished a deep hatred of Catholic priests. Turner, having recovered his mental balance, defended himself with vigour, although the four older priests allowed the young and able John Gavan to act as the principal spokesman for all five. Attempts to discredit the testimony of Titus Oates, the inventor of the Plot, by proving that he had been in St Omer for six months when he claimed to have been in London failed, as the Court ruled that the witnesses, being Catholics, could receive a dispensation to lie and were therefore not credible. Far more effective were the direct attacks on Oates himself; in particular, the accused were able to show that though Oates knew Whitbread and Fenwick personally, Gavan was a stranger to him. Oates’s evidence against Gavan was so feeble that even Scroggs remarked “I perceive your memory is not good”.

Despite weaknesses in the prosecution case, Scroggs summed up firmly for a conviction (while cheerfully admitting that he had already forgotten most of the evidence), and the jury delivered a guilty verdict within fifteen minutes. All five were hanged at Tyburn on 20 June 1679. The well-known story that they were offered a royal pardon on the scaffold if they would confess seems to have no foundation. Charles II was asked to show clemency, but refused, for fear of inflaming public opinion; the most he would do is order that the five be allowed to hang until they were dead, that they be spared drawing and quartering and given a proper burial.[10]

The crowd showed that its sympathy was with the victims, and stood in respectful silence while each of the condemned men delivered a last speech maintaining his innocence. They were buried in St Giles-in-the-Fields.

“Being now, good People, very near my End, and summon’d by a violent Death to appear before God’s Tribunal, there to render an account of all my thoughts, words, and actions, before a just Judge, I am bound in Conscience to declare upon Oath my Innocence from the horrid Crime of Treason, with which I am falsely accused: And I esteem it a Duty I owe to Christian Charity, to publish to the World before my death all that I know in this point, concerning those Catholicks I have conversed with since the first noise of the Plot, desiring from the very bottom of my heart, that the whole Truth may appear, that Innocence may be clear’d, to the great Glory of God, and the Peace and Welfare of the King and Country. As for my self, I call God to witness, that I was never in my whole life at any Consult or Meeting of the Jesuits, where any Oath of Secrecy was taken, or the Sacrament, as a Bond of Secrecy, either by me or any one of them, to conceal any Plot against His Sacred Majesty; nor was I ever present at any Meeting or Consult of theirs, where any Proposal was made, or Resolve taken or signed, either by me or any of them, for taking away the Life of our Dread Soveraign; an Impiety of such a nature, that had I been present at any such Meeting, I should have been bound by the Laws of God, and by the Principles of my Religion, (and by God’s Grace would have acted accordingly) to have discovered such a devillish Treason to the Civil Magistrate, to the end they might have been brought to condign punishment. I was so far, good People, from being in September last at a Consult of the Jesuits at Tixall, in Mr. Ewer’s Chamber, that I vow to God, as I hope for Salvation, I never was so much as once that year at Tixall, my Lord Aston’s House. ‘Tis true, I was at the Congregation of the Jesuits held on the 24th of April was twelve-month, but in that Meeting, as I hope to be saved, we meddled not with State-Affairs, but only treated about the Governours of the Province, which is usually done by us, without offence to temporal Princes, every third Year all the World over. I am, good People, as free from the Treason I am accused of, as the Child that is unborn, and being innocent I never accused my self in Confession of any thing that I am charged with. Which certainly, if I had been conscious to my self of any Guilt in this kind, I should not so frankly and freely, as I did, of my own accord, presented my self before the King’s Most Honourable Privy Council. As for those Catholicks, which I have conversed with since the noise of the Plot, I protest before God, in the words of a dying Man, that I never heard any one of them, neither Priest nor Layman, express to me the least knowledge of any Plot, that was then on foot amongst the Catholicks, against the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, for the advancing the Catholick Religion. I dye a Roman Catholick, and humbly beg the Prayers of such for my happy passage into a better Life: I have been of that Religion above Thirty Years, and now give God Almighty infinite thanks for calling me by his holy Grace to the knowledge of this Truth, notwithstanding the prejudice of my former Education. God of his infinite Goodness bless the King, and all the Royal Family, and grant His Majesty a prosperous Reign here, and a Crown of Glory hereafter. God in his mercy forgive all those which have falsely accused me, or have had any hand in my Death; I forgive them from the bottom of my heart, as I hope my self for forgiveness at the Hands of God.

O GOD who hast created me to a supernatural end, to serve thee in this life by grace and injoy thee in the next by glory, be pleased to grant by the merits of thy bitter death and passion, that after this wretched life shall be ended, I may not fail of a full injoyment of thee my last end and soveraign good. I humbly beg pardon for all the sins which I have com∣mitted against thy Divine Majesty, since the first Instance I came to the use of reason to this very time; I am heartily sorry from the very bottom of my heart for having offending thee so good, so powerfull, so wise, and so just a God, and purpose by the help of thy grace, ne∣ver more to offend thee my good God, whom I love above all things.

O sweet Jesus, who hath suffer’d a most painfull and ignominious Death upon the Cross for our Salvation, apply, I beseech thee, unto me the merits of thy sacred Passion, and sanctifie unto me these sufferings of mine, which I humbly accept of for thy sake in union of the sufferings of thy sacred Majesty, and in punishment and satisfaction of my sins.

O my dear Saviour and Redeemer, I return thee immortal thanks for all thou hast pleased to do for me in the whole course of my life, and now in the hour of my death, with a firm belief of all things thou hast revealed, and a stedfast hope of obteining everlasting bliss. I chearfully cast my self into the Arms of thy Mercy, whose Arms were stretched on the Cross for my Re∣demption. Sweet Jesus receive my Spirit.”

-please click on the image for greater detail

All you blessed men & women, pray for us.

Love,

Matthew