-by Randall Colton

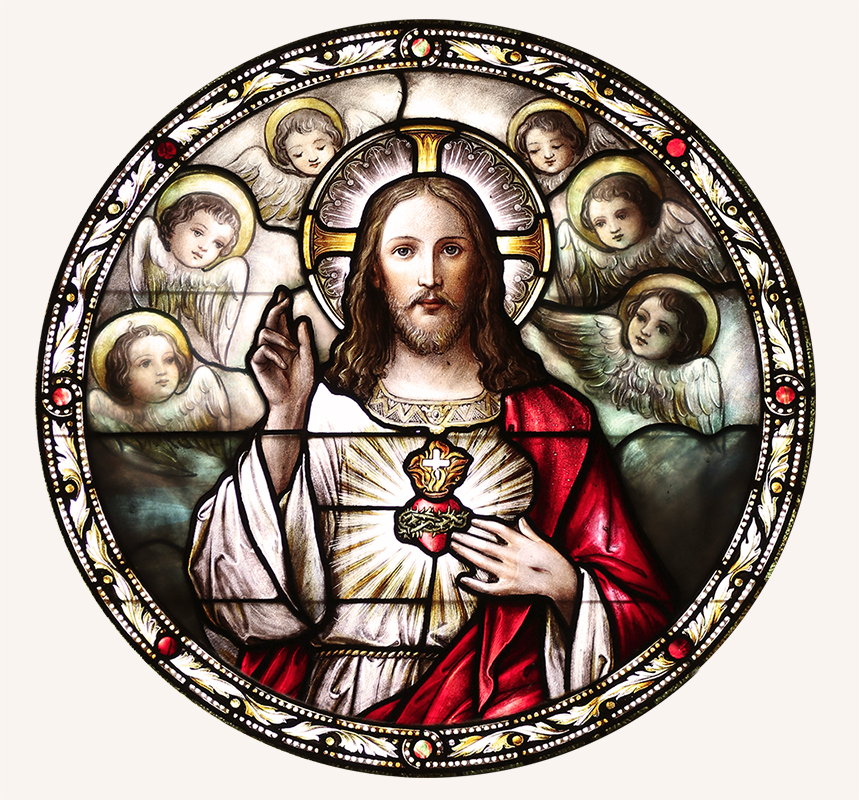

“On the 100th anniversary of Pope Leo XII’s consecration of the human race to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, John Paul II not only renewed his predecessor’s call for all to consecrate themselves to Christ, but also connected that devotion in a special way to the New Evangelization. From their contemplation of the pierced heart of the Redeemer, he said, Christians come away with a renewed sense of mission.

What, then, can evangelists learn from the Sacred Heart of Jesus? As Pius XII noted in his encyclical letter on the topic, devotion to the Sacred Heart constitutes, “so far as practice is concerned, a perfect profession of the Christian religion” (Haurietis Aquas 106). So, in a way, the evangelist can say, “Everything I really need to know, I learned from devotion to the Sacred Heart.”

In a more specific sense, perhaps the most important thing the evangelist can learn from the Sacred Heart is the virtue of meekness. Christ himself said, in his only direct reference to his heart, “Learn from me; for I am gentle and lowly of heart.” St. Peter later added, “Always be prepared to make a defense to any one who calls you to account for the hope that is in you, yet do it with gentleness and reverence” (1 Pet. 3:15). So it is in gentleness that the evangelist’s heart is most like the heart of Jesus.

What is gentleness? The Greek word translated as “gentleness” is also sometimes translated as “meekness” or “mildness.” For most English-speakers, though, “gentleness” is probably the most frequently used of those terms, and we hear it in a variety of contexts.

Suppose you bring a new baby home from the hospital to meet his siblings. You carefully situate him with his four-year-old sister, and you tell her, “Now, be gentle with him.”

Or suppose your six-year-old son wants to carry your grandfather’s pocket watch over to the window for a better look. You hand it to him with a warning: “Be gentle with it!”

Or perhaps you’ve just worked hard on an elaborate meal for your husband. As you begin, you say, “Tell me what you really think—but be gentle with me.”

We could imagine more scenarios, but perhaps these are enough to notice a certain commonality. Each of these cases features a difference in power or strength. The four-year-old is more powerful, stronger, even bigger than the baby, just as the six-year-old is with respect to the watch. The husband, in the third case, is more powerful than the wife, in the sense that his evaluation of her meal, and especially the way in which he communicates it, has the potential to build her up or to tear her down.

In each of these cases, the stronger must take special pains to ensure that his strength does not endanger the other. He must recognize the vulnerabilities of the other and the ways in which his strength can threaten those weaknesses, even when he bears no malice to the other. The gentle person, then, is one who protects the littleness and weakness of the other from the danger implied by his own bigness and power.

This definition of gentleness, however, fails to mention the one feature that is central to most traditional accounts. St. Thomas Aquinas, for example, teaches that meekness “moderates anger according to right reason” (Summa Theologica II:II:157). This emphasis on anger is common in the tradition, beginning as early as Aristotle.

I think a deep insight into anger ties these two definitions together. Aristotle, for example, points out that anger is a kind of pleasant emotion, because it leaves us feeling somehow superior to the object of our passion. If anger is, as Aristotle and St. Thomas believed, an apprehension of another as committing an unjust and undeserved offense against oneself, then to experience it is to see oneself in the right and the object of one’s anger as in the wrong.

And that confers a kind of advantage or relative strength over the offended party: standing on the moral high ground, he enjoys at least a moral superiority to the offender. That superiority can be used in such a way that the vulnerabilities of the offender are protected—or in such a way that they are threatened.

The traditional emphasis on restraint of anger as the defining characteristic of gentleness has a great deal of appeal. Anger, alienation, forgiveness, and reconciliation are at the heart of the moral life; learning to put these emotions and choices in the proper order is essential to any decent life with others. So the value of the virtue of gentleness first shines most brightly precisely in this arena.

But despite the fact that anger and its restraint play such important roles in the relationships among humans and between God and humanity, the moderation of anger does not exhaust the possibilities of gentleness, as our first examples above showed. We must not overlook the fact that gentleness is also called for in many contexts where anger is not the primary factor.

This larger reach of gentleness is not hard to see in the Sacred Heart of Jesus. What greater power differential could there be than that between the Word of God Incarnate, through whom all that exists came into being, and poor creatures like us? Yet the gospel tells us that he would not “break a bruised reed or quench a smoldering wick” (Matt. 12:20). Because his heart is meek, he tells us, his “yoke is easy” and his “burden is light” (11:30)—a burden suited to our weakness and not modeled after his strength.

Peter, as we noted before, urges Christians to imitate the gentleness of Jesus’ Sacred Heart precisely in their role as evangelists. “Always be ready to give an answer for the hope that is within you,” he teaches, “with gentleness and reverence.” Why does the evangelist need gentleness?

Evangelism in Peter’s day required gentleness first because Christians suffered great persecution. The very real possibility of abuse and mistreatment provided the context for this evangelistic admonition. And since innocent Christians could only experience such persecution as the infliction of undeserved harms, their anger would inevitably require shaping and restraining so that it would serve the good of their enemies. In the same way, Christ had allowed his heart to be pierced so that the fountain of his mercy could flow to the worst of his persecutors.

Most of us will not suffer such tribulation. But we can, nonetheless, be treated in unjust ways that arouse our anger. When that mistreatment comes to us because of our commitment to the truth that is Jesus, it is especially important that gentleness restrains our anger and leads us to the forgiveness and kindness we ourselves have already found in the Sacred Heart. Failing to respond gently will not only mean falling short of Jesus’ call to learn of his meek and lowly heart; it will also undercut our evangelistic efforts. How convincing can our proclamation of the truth be if we refuse to embody it in our actions?

Evangelists need gentleness for another reason. Knowledge of the truth is itself a kind of advantage that makes its possessor stronger. Consider, for example, the computer expert. If he intends to help the inexperienced user see the truths about computing, then he has to pursue gentleness, since the demoralization he could otherwise cause is an obstacle to learning.

How much more does the theological, moral, or apologetic “expert” pose a kind of threat to the relatively unlearned! These truths strike much more closely to the heart of a person’s self-understanding. A rough, ungentle approach to learners’ instruction can leave those already committed in some way to these truths feeling not just embarrassed, but positively foolish, as though they do not even understand their own deepest commitments. Such learners are likely to abandon the pursuit of deeper understanding, seeing it at best as an irrelevancy and at worst as a calculated attempt at the evangelist’s self-aggrandizement.

A lack of gentleness threatens to undermine the evangelist’s efforts in another way, too. Since evangelists ultimately strive to bring others to an encounter with Christ that results in conversion of life, the truths they teach touch the center of their hearers’ ways of life. Those who are not already committed to these truths quite reasonably perceive them as a threat to their self-identity. That sense of danger prompts almost impenetrable defenses. And those defenses usually cannot be forced in a frontal assault. Not pyrotechnics, but gentleness wins the day. As the Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand noted, “If spoken by the meek, the word of truth which like a sword, severs soul and body, subtly insinuates itself like a breath of love into the innermost recesses of the soul.”

Devotion to the Sacred Heart contains the key to cultivating this necessary gentleness. Gentleness comes from growing in union with the heart of Jesus, as we love, trust, and imitate Him more. Von Hildebrand sees this point well, and his insight captures the true power of gentleness: “For the meek is reserved true victory over the world, because it is not they themselves who conquer, but Christ in them and through them.”

Sacred Heart of Jesus, make our hearts like unto Thine.”

Love,

Matthew