The word martyr comes from the Greek μάρτυς, or mártys, which translates as “witness”. This is in as to witness, to give proof of one’s conviction and commitment to what one holds to be the Truth. This proof is given in one’s dying and suffering torment rather than apostatizing that Truth, or living under extremely difficult circumstances, or counter-cultural ways, or even just inconvenience/unpopularity/what is generally considered the minority opinion/way rather than make life easier for oneself/make oneself more popular by apostatizing that Truth.

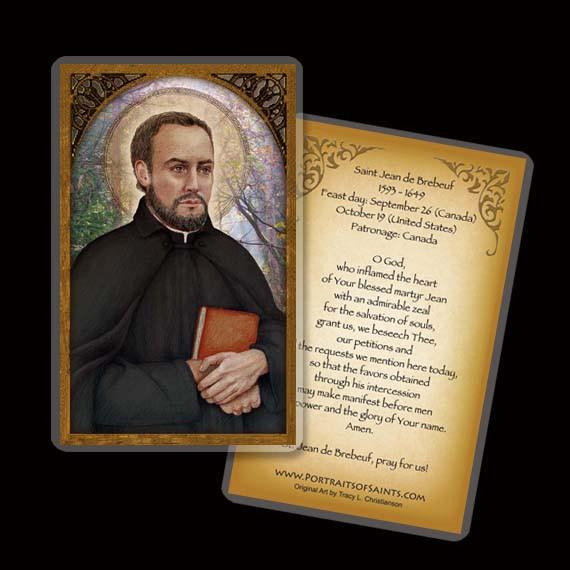

Jean de Brébeuf was born in Condé-sur-Vire, Normandy, France on 25 March 1593. He was the uncle of the poet Georges de Brébeuf. He studied near home at Caen. Jean could have elected a life of comfort near his family in France, but wanted to join the Society of Jesus from an early age. In humility, Jean’s desire was to become a Jesuit lay brother, but, in contrast to that, his superior convinced him to study for the priesthood. He entered the Society of Jesus as a scholastic, 8 November, 1617, aged 24 years.

Though of unusually robust physical strength, massive in physical stature his contemporaries describe him, his health gave way completely when he was twenty-eight to tuberculosis, which interfered with his studies and permitted only what was strictly necessary, so that he never acquired any extensive theological knowledge. He was almost expelled from the Society because his illness prevented both his studying and instruction for the traditional periods.

After teaching at a secondary school-college in Rouen, on February 19, 1622 Jean de Brebeuf was ordained. He became the treasurer of the college.

The tall, rugged Jesuit responded to an appeal made two years later by the Franciscan Recollects who asked other religious orders to help with the missions in New France. Against the voiced desires of Huguenot Protestants, officials of trading companies, and some native North Americans, he was granted his wish and in 1625 he sailed to Canada as a missionary, arriving on June 19, and lived with the Huron natives near Lake Huron, learning their customs and language, of which he became an expert (it is said that he wrote the first dictionary of the Huron language). He has been called Canada’s “first serious ethnographer.”

Arriving 19 June, 1625, in Quebec, with the Recollect, Joseph de la Roche d’ Aillon, and in spite of the threat which the Calvinist captain of the ship which had transported him made to carry him back to France, he remained in the colony. Jean overcame the dislike of the colonists for Jesuits and secured a site for a residence on the St. Charles, the exact location of a former landing of Jacques Cartier, the famous original French explorer of New France.

During that summer came a group of Hurons to Cap de la Victoire to barter for trade goods. Brébeuf, another Jesuit and a Franciscan went to meet them and asked to accompany them back to their homelands. The Hurons were willing to take the first two, but not Brébeuf who towered over them and was much too big for their canoes; they were afraid he would be too much work to carry. The missionaries offered enough gifts to overcome reluctance, and Brébeuf was permitted into a canoe on the condition he would not move. On July 26, 1626 Brébeuf began his journey to Huronia. When the travelers came to cascades or places where they had to carry the canoes and all the gear overland, Brébeuf’s great strength won his hosts’ admiration.

He immediately took up his abode in the Native American wigwams, and has left us an account of his five months’ experience there in the dead of winter. In the spring he set out with the Huron on a journey to Lake Huron in a canoe, during the course of which his life was in constant danger. With him was Father de Noüe, and they established their first mission near Georgian Bay, at Ihonatiria, but after a short time his companion was recalled, and he was left alone.

Brébeuf met with no success. The only converts he made during the winter of 1628 were the dying whom he baptized.

Because of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), in which France was engaged, Brébeuf was forced to return to France. He was summoned back to Quebec because of the danger of extinction to which the entire colony was then exposed, and arrived there after an absence of two years, 17 July, 1628. An English blockade had kept the French from resupplying the colony, so Brébeuf took 20 canoes loaded with grain to Quebec.

On 19 July, 1629, Champlain surrendered to the English, and the missionaries returned to France. For two years Brébeuf resumed his work at the college in Rouen. Four years after its fall, the colony was restored to France, and on 23 March, 1633, Brébeuf again set out for Canada. While in France he had pronounced his solemn vows as spiritual coadjutor.

As soon as he arrived, viz., May, 1633, he attempted to return to Lake Huron. The Indians refused to take him, but during the following year he succeeded in reaching his old mission along with Father Daniel. It meant a journey of thirty days and constant danger of death. The next sixteen years of uninterrupted labors among the Native Americans were a continual series of privations and sufferings which he used to say were only roses in comparison with what the end was to be. Brébeuf told many of his experiences in Canada in the “Jesuit Relations”, an invaluable source of early Canadian history.

He was head of the Huron mission, a position he relinquished to Father Jérôme Lalemant in 1638. His success as a missionary was very slow and it was only in 1635 that he made his first converts [Jesuit Relations, p. 11, vol. X]. He claimed to have made 14 as of 1635, and as of 1636 he said the number went up 86 [Jesuit Relations, p. 11,vol. X]. The Jesuits were frequently blamed for disasters like epidemics, battle defeats, and crop failures and once Brébeuf was condemned to death and another time beaten.

In 1640 he set out with Father Chaumonot to evangelize the Neutres/Neutrals, a tribe that lived north of Lake Erie. It is reported while there, in prayer, Jean de Brebeuf witnessed a large cross in the night sky over Iroquois territory. After a winter of incredible hardship the missionaries returned unsuccessful. Jean had to flee to Quebec after he was accused of plotting with Huron enemies, the Seneca Clan of the Iroquois, to betray his hosts.

Jean was given the care of the Indians in the Reservation at Sillery for three years. He returned to the Huron in 1644 and finally experienced some success. By 1647 there were thousands of converted Huron. In 1643 he wrote the Huron Carol, a Christmas carol which is still, in a very modified version, used today.

Brébeuf’s charismatic presence in the Huron country helped cause a split between traditionalist Huron and those who wanted to adopt European culture. Montreal-based ethnohistorian Bruce Trigger argues that this cleavage in Huron society, along with the spread of disease from Europeans, left the Huron vulnerable.

However, the Iroquois began to win their war with the Hurons. About the time the war was at its height between the Hurons and the Iroquois, Jogues and Bressani had been captured in an effort to reach the Huron country, and Brébeuf was appointed to make a third attempt. He succeeded. With him on this journey were Chabanel and Garreau, both of whom were afterwards murdered. They reached St. Mary’s on the Wye, which was the central station of the Huron Mission.

By 1647 the Iroquois had made peace with the French, but kept up their war with the Hurons, and in 1648 fresh disasters befell the work of the missionaries — their establishments were burned and the missionaries slaughtered. On 16 March, 1649, 1200 Iroquois captured the mission of St Ignace. They then attacked St. Louis and seized Brébeuf and fellow Jesuit, Fr. Gabriel Lallemant, SJ. A renegade Huron among the attackers let the Iroquois know that they had captured the mighty Echon, most powerful of the Jesuit medicine men. Both could have escaped. The Hurons at St Louis knew of the attack at St Ignace. They sent their women and children into the forest to hide and could have left, but remained. The Jesuit Fathers remained with their flock. All the men knew exactly what that meant. The two priests were dragged back to St. Ignace.

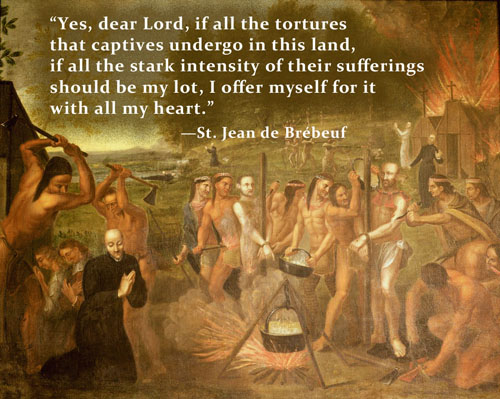

After some preliminary torture, the Jesuits and the Huron captives were forced to run naked through the snow. On entering the village, they were met with a shower of stones, cruelly beaten with clubs, and then tied to posts to be burned to death. Brébeuf is said to have kissed the stake to which he was bound. The fire was lighted under them, and their bodies slashed with knives. One of his Iroquois tormentors, crying out, ran towards him. “You have always told people it was good to suffer,’ he shouted. “Thank us for this!” And he dropped over Brebeuf’s head a cumbrous necklace of tomahawks, red-hot. Sputtering and hissing they began to eat their way into his flesh. His tormentors covered him with resinous bark which they set aflame. He continued encouraging his fellow Christians to remain strong. Then the Jesuit’s captors cut off his nose and forced a hot iron down his throat to silence him. The Jesuit priests were then tortured by scalping, mock baptism using boiling water, their feet were cut off, and their hearts were torn out. The torture-to-death went on for three hours.

Brébeuf did not make a single outcry while he was being tortured. It is recorded when Jesuits in New France would muse together if they should receive the crown of martyrdom, how would they stand it? Brebeuf commented, “I wouldn’t be thinking of myself. I would be thinking of God.” As every Saint before his time and since, John de Brebeuf knew well, you can’t put limits on love. If you succeed, all you really know is that love is dead.

The bravery the Iroquois witnessed that day from Brebeuf astounded even his most ardent tormentors and executioners. They admired courage during torture as witnessed by the silence of victim. Jean Brebeuf knew this. The Iroquois ate his heart in hopes of gaining his courage. A highest gallows compliment? Brébeuf was fifty-five years old. The Iroquois withdrew when they had finished their work.

Brébeuf’s body was recovered a few days later. His body was boiled in lye to remove the flesh, and the bones were reserved as holy relics. His flesh was buried, along with Lalemant’s, in one coffin, and today rests in the Church of St. Joseph at the reconstructed Jesuit mission of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons across Highway 12 from the Martyrs’ Shrine Catholic Church near Midland, Ontario. These martyrdoms and those of the other North American Martyrs created a wave of vocations and missionary fervor in France, and it gave new heart to the missionaries in New France.

A plaque near the grave of Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant was unearthed during excavations at Ste Marie in 1954. The letters read “P. Jean de Brébeuf /brusle par les Iroquois /le 17 de mars l’an/1649” (Father Jean de Brebeuf, burned by the Iroquois, 17 March 1649). The skull of St Jean Brébeuf, SJ, is still kept as a relic at the Hôtel-Dieu, Quebec.

St Jean de Brebeuf, SJ’s memory is cherished in Canada and has a pre-eminent position more than that of many of the other early missionaries. Their names appear with his in letters of gold on the grand staircases of public buildings in Canada. His memory is held sacred due to his heroic virtues, manifested in such a remarkable degree at every stage of his missionary career, his almost incomprehensible endurance of privations and suffering, and the conviction that the reason of his death was not his association with the Hurons, but hatred of Christianity.

15 September 1985, Pope John Paul II prayed over Brebeuf’s skull before saying an outdoor Mass on the grounds of the Martyrs’ Shrine, www.martyrs-shrine.com, one of nine National Shrines in Canada to the martyrs of North America in, including, among others, St. Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal and the Basilica of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, and other shrines in the territory of the United States. Thousands of people came to hear the Pope speak from a platform built especially for the day.

-Groupe Huron-Wendat Wendake, 1880.

The Huron People

(Ouendat/Wyandotte Nation/Wyandot/Wendat), “Dwellers of the Penninsula/Islanders”, as Wendat historic territory was bordered on three sides by the waters of Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe. Early French explorers referred to these natives as the Huron, either from the French huron (“ruffian”, “rustic”), or from hure (“boar’s head”). According to tradition, French sailors thought that the bristly hairstyle of Wendat warriors resembled that of a boar. They called their traditional territory Wendake/Quendake.

A Roman cassock often has a series of buttons down the front – sometimes thirty-three (symbolic of the years of the life of Jesus). A Jesuit cassock, although Jesuits have no official habit or distinctive religious garb, in lieu of buttons, has a fly fastened with hooks at the collar and is bound at the waist with a black cincture knotted on the right side. It was the common priestly dress of St Ignatius’ day, who founded the Society of Jesus. During the missionary periods of North America, the various native peoples referred to Jesuits as “Blackrobes” because of their black cassocks.

The Wendat called St Jean de Brebeuf, SJ, “Echon”. [“Echon” pronounced like “Ekon” – this name meaning “Healing Tree”, as a representation of how much Brébeuf had helped the Hurons and of the medicines he brought them from Europe. An alternate definition for “Echon” is “he who bears the heavy load”, as Brébeuf was massive in stature and carried more than his share when working with the Ouendat people. John Steckley wrote that Jean de Brébeuf was the first of the Jesuits (hatitsihenstaatsi’, ‘they are called charcoal’) due to their coal black cassocks, to become fluent in their language.

The Huron were surprised at his endurance in the harsh and hearty climate of what is now Ontario. His massive size made them think twice about sharing a canoe with him for fear it would sink. Brebeuf had great difficulty learning the Huron language.

“When you come to us (Brebeuf wrote to Jesuits in France) we will receive you with open arms into the vilest dwelling imaginable. A mat, or at best a skin, will be your bed and often enough you will not sleep at all because of the vermin that will swarm over you. If you have been a great theologian in France, you will have to be a humble scholar here and taught by an unlearned person, or by children, while you furnish them no end of amusement. Here you will merely be a student, and with what teachers! The Huron language will be your Aristla crosse. The Huron tongue will be St. Thomas and Aristotle, and you will be happy if after a great deal of hard study you are able to stammer out a few words.

The winter is almost unendurable. As for leisure time, the Hurons will give you no rest night or day.

You may expect to be killed at any moment, and your cabin, which is highly flammable, may often take fire through carelessness or malice. You are responsible for the weather, be it foul or fair, and if you don’t bring rain when it’s needed you may be tomahawked for your lack of luck. And there are foes from without to reckon with. On the 13th of this month a dozen Hurons were killed at Contarea, which is only a few days’ distance from here; and a short time ago a number of Iroquois were discovered in ambush quite close to the village.

In France you are surrounded by splendid examples of virtue. Here, all are astonished when you speak of God. Blasphemy and obscenity are common things on their lips. Often you are without your Mass, and when you do succeed in saying it the cabin is full of smoke or snow. Your neighbors never leave you alone and are continually shouting at the top of their voices.

The food will be insipid, but the gall and vinegar of Our Blessed Saviour will make it like honey on your lips. Clambering over rocks and skirting cataracts will be pleasant if you think of Calvary; and you will be happy if you have lost the trail, or are sick and dying with hunger in the woods…

There is no danger for your soul, if you bring into this Huron country the love and fear of God. In fact I find many helps to perfection. For in the first place, you have only the necessaries of life, and that makes it easy to be united with God.

As for your spiritual exercises you can attend to them; you have nothing else to do except study Huron and talk with the Indians. And what pleasure there is for a heart devoted to God to make itself a little scholar of children, thereby gain them for God!

How willingly and liberally God communicates Himself to a soul who practices such humility through love of Him. The words he learns are so many treasures he amasses, so many spoils he carries off from the common enemy of mankind. And so the visits of the Indians no matter how frequent cannot be annoying to such a man. God teaches him the beautiful lesson he taught of old to St. Catherine of Siena to make of his heart a room or temple for Him where he will never fail to find him as often as he withdraws into it so that, if he encounters people there, they do not interfere with his prayers, they serve only to make them more fervent; from this he takes occasion to present these poor people to His Sovereign Goodness, and to entreat Him warmly for their conversion.

Of course you have nothing in the way of externals to increase your devotion, but God makes up for it. Have we not the Blessed Sacrament in the house? Moreover, we have to trust in God: there is no other help available.

And now, if after contemplating the sufferings that await you, you are ready to say “Amplius, Domine! Still more, Lord!” then be sure that you will be rewarded with consolations to such a degree that you will be forced to cry: “Enough, O Lord, enough!”

Jean Brebeuf, SJ, eventually wrote a catechism in Huron, and a French-Huron dictionary for use by other missionaries.

The Huron

The total population of the Huron at the time of European contact has been estimated at about 20,000 to 40,000 people. From 1634 to 1640, the Huron were devastated by Eurasian infectious diseases, such as measles and smallpox, to which they had no immunity. Epidemiological studies have shown that beginning in 1634, more European children immigrated with their families to the New World from cities in France, England, and the Netherlands that had endemic smallpox. Historians believe the disease spread from the children to the Huron and other nations. Numerous Huron villages and areas were permanently abandoned. About two-thirds of the population died in the epidemics, decreasing the population to about 12,000.

Before the French arrived, the Huron had already been in conflict with the Iroquois nations to the south. Several thousand Huron lived as far south as present-day central West Virginia along the Kanawha River by the late 16th century, but they were driven out by the Iroquois’ invading from present-day New York in the 17th century.

Once the European powers became involved in trading, the conflict among natives intensified significantly as they struggled to control the trade. The French allied with the Huron, because they were the most advanced trading nation at the time. The Iroquois tended to ally with the Dutch. Introduction of European weapons and the fur trade increased the severity of inter-tribal warfare, “Le Longue Carabine”.

In James Fenimore Cooper’s Feb 1826 novel, “The Last of the Mohicans”, first published in Philadelphia, set in 1757 in what is now New York state, the antagonist, Magua, is a Huron chief.

Surviving Jesuits burned the mission of St Ignace after abandoning it to prevent its capture. The Iroquois attack shocked the Huron. By May 1, 1649, the Huron burned 15 of their villages to prevent their stores from being taken and fled as refugees to surrounding tribes. About 10,000 fled to Gahoendoe (Christian Island).

Most who fled to the island starved over the winter, as it was a non-productive settlement and could not provide for them. Those who survived were believed to have resorted to cannibalism to do so. After spending the bitter winter of 1649-50 on Gahoendoe, surviving Huron relocated near Quebec City, where they settled at Wendake. Absorbing other refugees, they became the Huron-Wendat Nation. Some Huron, along with the surviving Petuns, whose villages were attacked by the Iroquois in the fall of 1649, fled to the upper Lake Michigan region, settling first at Green Bay, then at Michilimackinac. The western Wyandot eventually re-formed across the border in the area of present-day Ohio and southern Michigan in the United States. Some descendants of the Wyandot Nation of Anderdon still live in Ohio and Michigan.

In the 1840s, most of the surviving Wyandot people were displaced to Kansas through the US federal policy of forced Indian removal. Using the funds they received for their lands in Ohio the Wyandot purchased 23,000 acres (93 km2) of land for $46,080 in what is now Wyandotte County, Kansas in the Kansas City, Kansas area from the Delaware who were grateful for the hospitality the Wyandot had shown them in Ohio. It was a more-or-less square parcel north and west of the junction of the Kansas River and the Missouri River.

In February 1985 the U.S. government agreed to pay descendants of the Wyandot $5.5 million. The decision settled the 143-year-old treaty, which in 1842 forced the tribe to sell their Ohio lands for half of its fair value.

In 1999, representatives of the far-flung Wyandot bands of Quebec, Kansas, Oklahoma and Michigan gathered at their historic homeland in Midland, Ontario. They formally re-established the Wendat Confederacy.

Each modern Wyandot community is an autonomous band:

- Huron-Wendat Nation, at Wendake, now within the Quebec City limits, approximately 3,000 members

- Wyandot Nation of Anderdon, in Michigan, with headquarters in Trenton, Michigan, perhaps 800 members

- Wyandot Nation of Kansas, with headquarters in Kansas City, Kansas, perhaps 400 members

- Wyandotte Nation, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Wyandotte, Oklahoma, with 4,300 members.

The approximately 3,000 Wyandot in Quebec are primarily Catholic and speak French as a first language. They have begun to promote the study and use of the Wyandot language among their children.

St Jean de Brebeufs, SJ’s Legacy

Many Jesuit schools are named after St John de Brebeuf, SJ, such as Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf in Montreal, Brébeuf College School in Toronto and Brebeuf High School in Indianapolis, Indiana. There is also St. John de Brebeuf Catholic High School in Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada; and Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. There is also Eglise St-Jean de Brebeuf in Sudbury, Ontario.

St John de Brebeuf’s feast day in Canada is celebrated on September 26, while in the United States it is celebrated on October 19.

It is said that the modern name of the Native North American sport of lacrosse was first coined by Brébeuf who thought that the sticks used in the game reminded him of a bishop’s crosier (crosse in French, and with the feminine definite article, la crosse).

Brebeuf’s Instructions to the Missionaries: In 1637, Father Brebeuf drew up a list of instructions for Jesuit missionaries destined to work among the Huron. They reflect his own experience, and a genuine sensitivity toward the native people.

- You must love these Hurons, ransomed by the blood of the Son of God, as brothers.

- You must never keep the Indians waiting at the time of embarking.

- Carry a tinder-box or a piece of burning-glass, or both, to make fire for them during the day for smoking, and in the evening when it is necessary to camp; these little services win their hearts.

- Try to eat the little food they offer you, and eat all you can, for you may not eat again for hours.

- Eat as soon as day breaks, for Indians when on the road, eat only at the rising and the setting of the sun.

- Be prompt in embarking and disembarking and do not carry any water or sand into the canoe.

- Be the least troublesome to the Indians.

- Do not ask many questions; silence is golden.

- Bear with their imperfections, and you must try always to appear cheerful.

- Carry with you a half-gross of awls, two or three dozen little folding knives, and some plain and fancy beads with which to buy fish or other commodities from the nations you meet, in order to feast your Indian companions, and be sure to tell them from the outset that here is something with which to buy fish.

- Always carry something during the portages.

- Do not be ceremonious with the Indians.

- Do not begin to paddle unless you intend always to paddle.

- The Indians will keep later that opinion of you which they have formed during the trip.

- Always show any other Indians you meet on the way a cheerful face and show that you readily accept the fatigues of the journey.

The Huron Carol

The “Huron Carol” (or “‘Twas in the Moon of Wintertime”) is a Canadian Christmas hymn (Canada’s oldest Christmas song), written in 1643 by Jean de Brébeuf. Brébeuf wrote the lyrics in the native language of the Huron/Wendat people; the song’s original Huron title is “Jesous Ahatonhia” (“Jesus, he is born”). The song’s melody is based on a traditional French folk song, “Une Jeune Pucelle” (“A Young Maid”). The well-known English lyrics were written in 1926 by Jesse Edgar Middleton.

The English version of the hymn uses imagery familiar in the early 20th century, in place of the traditional Nativity story. This version is derived from Brebeuf’s original song and Huron religious concepts. In the English version, Jesus is born in a “lodge of broken bark”, and wrapped in a “robe of rabbit skin”.

He is surrounded by hunters instead of shepherds, and the Magi are portrayed as “chiefs from afar” that bring him “fox and beaver pelts” instead of the more familiar gold, frankincense, and myrrh. The hymn also uses a traditional Algonquian name, Gitchi Manitou, for God. The original lyrics are now sometimes modified to use imagery accessible to Christians who are not familiar with Native-Canadian cultures.

The song remains a common Christmas hymn in Canadian churches of many Christian denominations. Canadian singer Bruce Cockburn has also recorded a rendition of the song in the original Huron. It was also sung by Canadian musician Tom Jackson during his annual Huron Carole show. The group ‘Crash Test Dummies’ recorded this hymn on their album “Jingle all the Way” (2002). In the United States, the song was included as “Jesous Ahatonia” on Burl Ives’s 1952 album Christmas Day in the Morning and was later released as a Burl Ives single under the title “Indian Christmas Carol.” The music has been rearranged by the Canadian songwriter Loreena McKennitt under the title “Breton Carol” in 2008.

The Hurons who escaped the Iroquois attacks preserved the hymn. Father Étienne de Villeneuve, SJ recorded the words of the hymn, which were found among his papers following his death in 1794.

We see in this carol a fine instance of genuine inculturation, as St. Jean de Brébeuf, SJ, strove to express the universal truths of Christian faith in an idiom intelligible to the Hurons among whom he preached.

Guide to Pronunciation:

e – like ‘eh’

8 = ‘w’ before vowel

‘u’ before consonant

i – like ‘ee’ in ‘freeze’,

= ‘y’

a – like ‘ah’

th = t followed by an aspiration

on – as in the French word ‘bon’ en – as in the French word ‘chien’

an – as in the French word ‘viande’

Accents tend to fall on the 2nd last syllable

Iesous Ahatonnia (ee-sus a-ha-ton-nyah= Jesus, he is born)

Estennia,on de tson8e Ies8s ahatonnia

eh-sten-nyah-yon deh tson-weh ee-sus a-ha-ton-nyah

Have courage, you who are humans, Jesus, he is born

Onn’a8ate8a d’oki n’on,8andask8aentak

on-nah-wah-teh-wah do-kee non-ywah-ndah-skwa-en-tak

Behold, the spirit who had us as prisoners has fled

Ennonchien sk8atrihotat n’on,8andi,onrachatha

en-non-shyen skwah-tree-hotat non-ywa-ndee-yon-rah-shah-thah

Do not listen to it, as it corrupts our minds

Iesus ahatonnia

A,oki onkinnhache eronhia,eronnon

ayo-kee on-kee-nhah-sheh eh-ron-hya-yeh-ron-non

They are spirits, coming with a message for us, the sky people

iontonk ontatiande ndio sen tsatonnharonnion

yon-tonk on-tah-tya-ndeh ndyo sen tsah-ton-nha-ron-nyon

they are coming to say, “Rejoice” (ie., be on top of life)

8arie onna8ak8eton ndio sen tsatonnharonnion

wah-ree on-nah-wah-kweh-ton ndyo sen tsah ton-nha-ron-nyon

“Marie, she has just given birth. Rejoice.”

Ies8s ahatonnia

Achink ontahonrask8a d’hatirih8annens

a-shien-k on-tah-hon-rah-skwah dhah-tee-ree-hwan-nens

Three have left for such a place, those who are elders

Tichion ha,onniondetha onh8a achia ahatren

tee-shyon ha-yon-nyon-deh-tha on-hwah a-shya ah-hah-tren

A star that has just appeared over the horizon leads them there

Ondaiete hahahak8a tichion ha,onniondetha

on-dee teh-hah-hah-hah-kwah tee-shyon ha-yon-nyon-deh-tha

He will seize the path, he who leads them there

Ies8s ahatonnia

Tho ichien stahation tethotondi Ies8s

thoh ee-shyen stah-hah-tyon teh-tho-ton-ndee ee-sus

As they arrived there, where he was born, Jesus

ahoatatende tichion stan chi teha8ennion

ah-ho-a-tah-ten-nde tyee-shyon stan shee teh-hah-wen-nyon

the star was at the point of stopping, he was not far past it

Aha,onatorenten iatonk atsion sken

a-hah-yon-ah-to-ren-ten yah-tonk ah-tsyon sken

Having found someone for them, he says, “Come here”

Ies8s ahatonnia

Onne ontahation chiahona,en Ies8s

on-nen on-tah-hah-tyon shyah-hon-ah-yen ee-sus

Behold, they have arrived there and have seen Jesus

Ahatichiennonniannon kahachia handia,on

ah-hah-tee-shyen-non-nyan-non kah-hah-shyah hah-ndyah-yon

They praised (made a name) many times, saying “Hurray, he is good in nature”

Te honannonronk8annnion ihontonk oerisen

teh-hon-an-non-ron-kwan-nyon ee-hon-tonk o-eh-ree-sen

They greeted him with reverence (i.e., greased his scalp many times), saying “Hurray”

Iesus ahatonnia

Te hek8atatennonten ahek8achiendaen

teh-heh-kwah-tah-ten-non-ten ah-heh-kwah-shyen-ndah-en

“We will give to him praise for his name”

Te hek8annonronk8annion de son,8entenrande

teh-heh-kwan-non-ron-kwan-nyon deh son-ywen-ten-ran-ndeh

“Let us show reverence for him as he comes to be compassionate to us.”

8to,eti sk8annonh8e ichierhe akennonhonstha u-to-yeh-tee

skwan-non-hweh ee-shyeh-rheh ah-keh-non-hon-sthah

“It is providential that you love us and wish, “I should adopt them.”

Ies8s ahatonnia

Translated by Mildred Milliea, edited by Eskasoni Elder’s Committee, and sung by the Eskasoni Trio. copyright (c) 2001

Na kesikewiku’sitek jipji’jk* majita’titek

It was in the moon of the wintertime when all the birds had fled

Kji-Niskam petkimasnika ansale’wilitka

That mighty Gitchi Manitou sent angels

Kloqoejuitpa’q, Netuklijik nutua’tiji.

On a starlit night hunters heard

Se’sus eleke’wit, Se’sus pekisink, ewlite’lmin

Jesus your King is born, Jesus is born, In-ex-cel-sis-gloria

Ula nqanikuomk etli we’ju’ss mijua’ji’j

Within the lodge of bark the tender Babe was found

Tel-klu’sit euli tetpoqa’tasit apli’kmujuey

A ragged robe of rabbit skin enwrapped His beauty round

L’nu’k netuklijik nutua’tiji ansale’wiliji.

But as the hunter braves drew near the angel’s song rang loud and high

Se’sus eleke’wit, Se’sus pekisink, eulite’lmin

Jesus your King is born, Jesus is born, In-ex-cel-sis-gloria

O’ mijua’ji’jk nipuktukewe’k, O’ Niskam wunijink

O children of the forest free, O God’s children

Maqmikek aq Wa’so’q tley ula mijua’ji’j

The Holy Child of Heaven and Earth

Pekisink kiskuk wjit kilow, pekisitoq wantaqo’ti.

Has come today for you has brought peace

Se’sus eleke’wit, Se’sus pekisink, eulite’lmin

Jesus the King is born, Jesus has come, In-ex-cel-sis-gloria

*The Mi’kmaw word “sisipk” is preferred by many to “jipji’jk” for “birds”.

Listen:

http://firstnationhelp.com/06_huron_carol.mp3

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6IG6F6E5Ac

Spiritual Formation of St Jean de Brebeuf, SJ

“His death has put the crown upon his life.” So Father Ragueneau, SJ, as on that distant April day at Fort Ste. Marie he concluded. He closed the little spiritual diary of the Saint which had lain open before him. It was difficult to brush away the haunting recollections of this man who just a few weeks ago had died a martyr at St. Ignace a mere six miles away. Sternly he set himself to completing the more prosaic details of his 1649 report to his superior back in France. Father Ragueneau, SJ, who had lived intimately with Father de Brefeuf for the last twelve years and who knew him well, was right. Fr. Jean de Brebeuf, SJ, by deliberate choice had worn the red, regal robes of a martyr ever since he entered the Jesuit Novitiate in Rouen thirty-one years before, and for love of Him who had previously passed that way had trodden, the rest of his days, down the long Royal Road of the Cross. On March 16, 1649, he found shining at its end the reward the crown accorded Paul and Lawrence and Sebastian and legions of Christ’s nobility before him. The fitting culmination of a martyr’s life was a martyr’s death.

Although he came from a France then in spiritual ferment, Brebeuf’s inner life remained to the end simple, direct, resolvable into one or two easily recognized elements. Its fibrous centre was the Jesuit Rule, its inspirational source the Passion of Our Lord, its overall characteristic daily, hourly martyrdom.

For almost twenty years before his death, Brebeuf’s resolution had been: “I’ll burst rather than voluntarily break any rule.” Such a resolve, if kept (and on the testimony of Ragueneau we know that it was kept), would alone be enough to make a man a Saint. It had been enough already to make a Saint of his fellow Jesuit, the Belgian John Berchmans, who died at Rome 1621, the year that Brebeuf became a sub-deacon.

Brebeuf’s forced return to France in 1629, his hopes for a missioner’s life and for a martyr’s death apparently dashed forever, was a spiritual milestone. He spent three brief years in France at this time, pegged to the distracting job of Bursar in a busy college. Yet for him these years were what a near lifetime passed in desert solitude might have been to some early eremite. They were fruitful years of probing self-knowledge, of, deepening and of simplification. During this period, his inner life assumed characteristics that would remain and single him out, among a hundred apparently similar saints, to the end of his days. This was the time when he set the perfect observance of the Rule of the Society of Jesus at the very centre of his spiritual life. It was during this period, as well, that he began really to lay bare the inexhaustible riches of Our Lord’s Passion. Now too came more sharply into focus his program of daily, hourly, self-inflicted martyrdom, since the possibility of that other martyrdom seemed forever removed. And at this time he was initiated, briefly, into the mystical life.

When David Kirke forced the French regime and the Jesuit missionaries temporarily out of New France he was doing a better thing than he knew. He was instrumental in providing strong impetus to the formation of a mystic and a saint.

Brebeuf was a giant, physically and spiritually, and so we are not surprised when he goes forward with great strides where other men, even other saints, appear to creep. But the reason for his swift progress lay ultimately in the motive which prompted him, the Love of God, the strongest as well as the highest of all possible motives. This is especially apparent when he starts earnestly and methodically to weave the red strands of the Passion into the pattern of his life. Many a holy man has, at least in the beginning, been impelled to a life of reparative suffering at the thought of his own earlier sins. Not so Brebeuf. With him it was love for Love. In his heart the pained cry of the first St. Ignatius, “My Love is crucified!” found true and responsive echo.

“I feel a great longing to suffer something for Christ,” he wrote in January, 1630 simply that, without further qualification except to say that God is treating him so gently these days that he is beginning to fear that he must be lost. Later in the same month he speaks of his sins, but only to balance them off against God’s goodness to him, and ingratitude to ask, “Lord, make me a man after Thine own Heart.” And paraphrasing that other great lover, St. Paul, he goes on to protest: “Nothing henceforward shall separate me from Thy love, not nakedness, not the sword, not death.”

-The Inner Flame of St John Brebeuf”, Elmer O’Brien, SJ

“For two days now I have experienced a great desire to be a martyr and to endure all the torments the martyrs suffered.

Jesus, my Lord and Savior, what can I give you in return for all the favors you have first conferred on me? I will take from your hand the cup of your sufferings and call on your name. I vow before your eternal Father and the Holy Spirit, before your most holy Mother and her most chaste spouse, before the angels, apostles and martyrs, before my blessed fathers Saint Ignatius and Saint Francis Xavier—in truth I vow to you, Jesus my Savior, that as far as I have the strength I will never fail to accept the grace of martyrdom, if some day you in your infinite mercy would offer it to me, your most unworthy servant.

I bind myself in this way so that for the rest of my life I will have neither permission nor freedom to refuse opportunities of dying and shedding my blood for you, unless at a particular juncture I should consider it more suitable for your glory to act otherwise at that time. Further, I bind myself to this so that, on receiving the blow of death, I shall accept it from your hands with the fullest delight and joy of spirit. For this reason, my beloved Jesus, and because of the surging joy which moves me, here and now I offer my blood and body and life. May I die only for you, if you will grant me this grace, since you willingly died for me. Let me so live that you may grant me the gift of such a happy death. In this way, my God and Savior, I will take from your hand the cup of your sufferings and call on your name: Jesus, Jesus, Jesus!

My God, it grieves me greatly that you are not known, that in this savage wilderness all have not been converted to you, that sin has not been driven from it. My God, even if all the brutal tortures which prisoners in this region must endure should fall on me, I offer myself most willingly to them and I alone shall suffer them all.”

-from the spiritual diary of St Jean de Brebeuf, SJ

Father, You consecrated the first beginnings of the faith in North America by the preaching and martyrdom of Saints John and Isaac and their companions. By the help of their prayers may the Christian faith continue to grow throughout the world. We ask this through our Lord Jesus Christ, Your Son, who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

-Brebeuf & Lalemant gravesite

Saint Jean de Brébeuf, obtain for me, through your intercession, courage to overcome all human respect, resignation in times of trial, confidence in God’s power and goodness, and zeal for my spiritual welfare; so that, raised above the things of earth, I may lead a truly Christian life and gain merit for eternity. Amen.

“God is the witness of our sufferings and will soon be our exceedingly great reward.”

-St. Jean de Brébeuf

“If I speak in human and angelic tongues but do not have love, I am a resounding gong or a clashing cymbal. And if I have the gift of prophecy and comprehend all mysteries and all knowledge; if I have all faith so as to move mountains but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away everything I own, and if I hand over my body to be burned so that I may boast but do not have love, I gain nothing.”

-1 Cor 13:1-3

Love,

Matthew