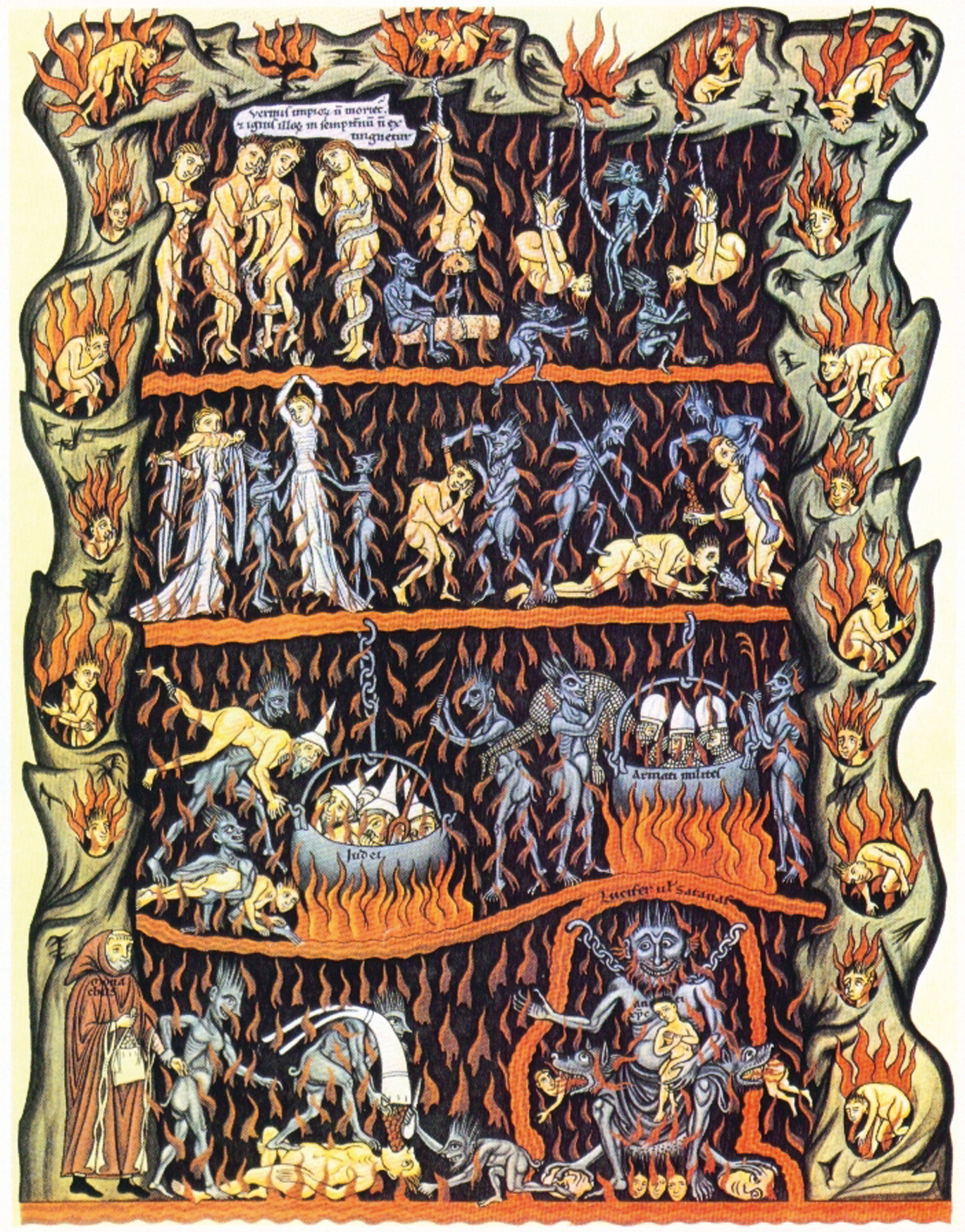

-Medieval illustration of Hell in the Hortus deliciarum manuscript of Herrad of Landsberg (about 1180), please click on the image for greater detail

-by Pat Flynn

“The Catholic Church has condemned what is sometimes called strong or hard universalism, the idea that we know that everybody is saved. Perhaps weak or soft universalism may be true, which is to say, perhaps everybody, at the end of the day, just so happens to be saved, though it could have been otherwise. So far as I’m aware, Catholics can maintain the soft or weak (or hopeful) universalist view. Whether there are good reasons to is a debate I will not enter now.

On the other hand, there is “infernalism,” a pejorative term for the traditional doctrine of hell. But how can hell be compatible with an all-good God? Let’s see.

Some universalists suggest that hell is impossible because of infinite opportunities for people to repent. In other words, in some sort of war of attrition, God will inevitably win us over. But this ignores a classic position—namely, the postmortem fixity of the will. The idea is that we eternally separate from God and thus eternally will the consequences and punishments thereof. Thus, properly understood, hell is not an infinite consequence for a finite sin, but rather an eternal consequence for an eternal act (orientation) of the will.

In simple terms, the account of postmortem fixity is this: to change our minds, we must either come across new information or consider the information we have from a new perspective. But a traditional understanding of the human person maintains that neither of these conditions attains upon death, when the intellect is separated from the body. In effect, we “angelize” upon death, and the orientation of our will at that point remains thereafter. Nothing “new” or “different” is going to come along to get us to consider things afresh. Although God could perform a “spiritual lobotomy” on everybody who makes the faulty judgment of willing against Gain, God—in His perfectly wise governance—orders things toward their end in accord with their nature. And our nature is one of a fallible liberty—we are free, and we are free to make mistakes, which we do.

God is not going to constantly override our faulty (though culpable) judgments, as that would amount to the constant performance of something on the order of a miracle, which would make nonsense of generating nature (particularly human nature) to begin with. And God isn’t the business of nonsense.

In my experience of introducing the concept of postmortem fixity to universalists, several of them have not only seemed unaware of this traditional teaching, but responded by calling it “strange.” The teaching, however, is not strange; rather, it follows straightforwardly from a traditional metaphysical understanding of the human person, as Edward Feser explains in this lecture. It appears to be a highly probable, if not inevitable, consequence, of good philosophical analysis of the human person.

Now, I said that our nature is one of a fallible liberty, and this too is an important point. Only God (who is subsistent goodness itself) is his own rule; God alone is naturally impeccable, always perfect. Nothing else—neither man nor angel—is like this, and so every being of created liberty must be capable of failing to consider and subsequently apply the moral rule in every instance of judgment, and therefore be capable of sin. In other words, God could no more have created an infallible free creature than he could a square circle.

To appreciate this fact is to appreciate why God, if wanting to bring about creatures like us, necessarily brings about the possibility of our sinning and turning from him. In this sense, love—which requires the uniting of free independent wills—is inherently risky, especially when only one will (God’s) is incapable of sinning.

Now, if we apply the notions above—fallible liberty and postmortem fixity—to God’s mode of governance, we can see why God not only permits our moral failures in this life, but would continue to permit our moral failure to love him in the next life. God is under no obligation to override our moral miscalculation, even if he could. Nor is God any less perfect for not doing so, since it is a matter of Catholic dogma that everyone receives sufficient grace—that is, everything he needs to love God and reject sin. Nobody fails to love God because of what God doesn’t give him; people fail to love God because they indulge in voluntary and therefore culpable ignorance (that is, fail to consider what they habitually know, and really could consider), deciding instead to love some inferior good. If that is the final choice they make, God respects it.

Again, it is not enough for the universalist to dismiss these notions as seeming archaic or strange or what have you. The claim of many universalists, after all, is that universalism is necessarily true, but these notions show that that is not the case. If we have strong independent reason to think universalism is not true—say, from Scripture and Tradition—then all we need are possibilities (not certainties) for why God allows hell and its compatibility with God’s goodness. My suggestion is that a proper understanding of finite fallible liberty, God’s being a perfectly wise governor, and the possibility of the postmortem fixity of the will provide the necessary conceptual resources we need to show the compatibility between an all-good God and the doctrine of hell.

Let me address two other arguments. I’ve heard it said by universalists that God could not be perfectly joyful if anybody were in hell, but God is perfectly joyful; ergo, there can be no one in hell. But if this argument proves anything, it proves too much. After all, if God cannot be perfectly joyful if somebody is in hell, then how can God be perfectly joyful in light of any sin or evil? The answer, obviously, is that he cannot be, and so the position makes God dependent upon creation. If that’s the case, God is no longer really God , who should be in no way dependent upon creation for his perfection. So that argument is not a good one.

Finally, justice and punishment. Part of what motivates universalists are faulty (or at least non-traditional) notions of both. Traditionally, punishment, even eternal punishment, has been seen as itself a good, itself an act of mercy and justice. Boethius stressed this point strongly: it is objectively better for a perpetrator to be punished than to get away with his crime.

As put in The Consolation of Philosophy, “The wicked, therefore, at the time when they are punished, have some good added to them, that is, the penalty itself, which by reason of its justice is good; and in the same way, when they go without punishment, they have something further in them, the very impunity of their evil, which you have admitted is evil because of its injustice . . . Therefore the wicked granted unjust impunity are much less happy than those punished with just retribution.”

If Boethius is right, then hell could—perhaps even should—be seen as God extending the most love, mercy, goodness he can to someone in a self-imposed exile. Ultimately, what would be contrary to justice (giving one what he is due) would be for somebody to eternally reject God and get away with it.

PS: For an extended rebuttal of strong-form universalism, see my recent conversation with Fr. James Rooney.”

Love & His mercy,

Matthew