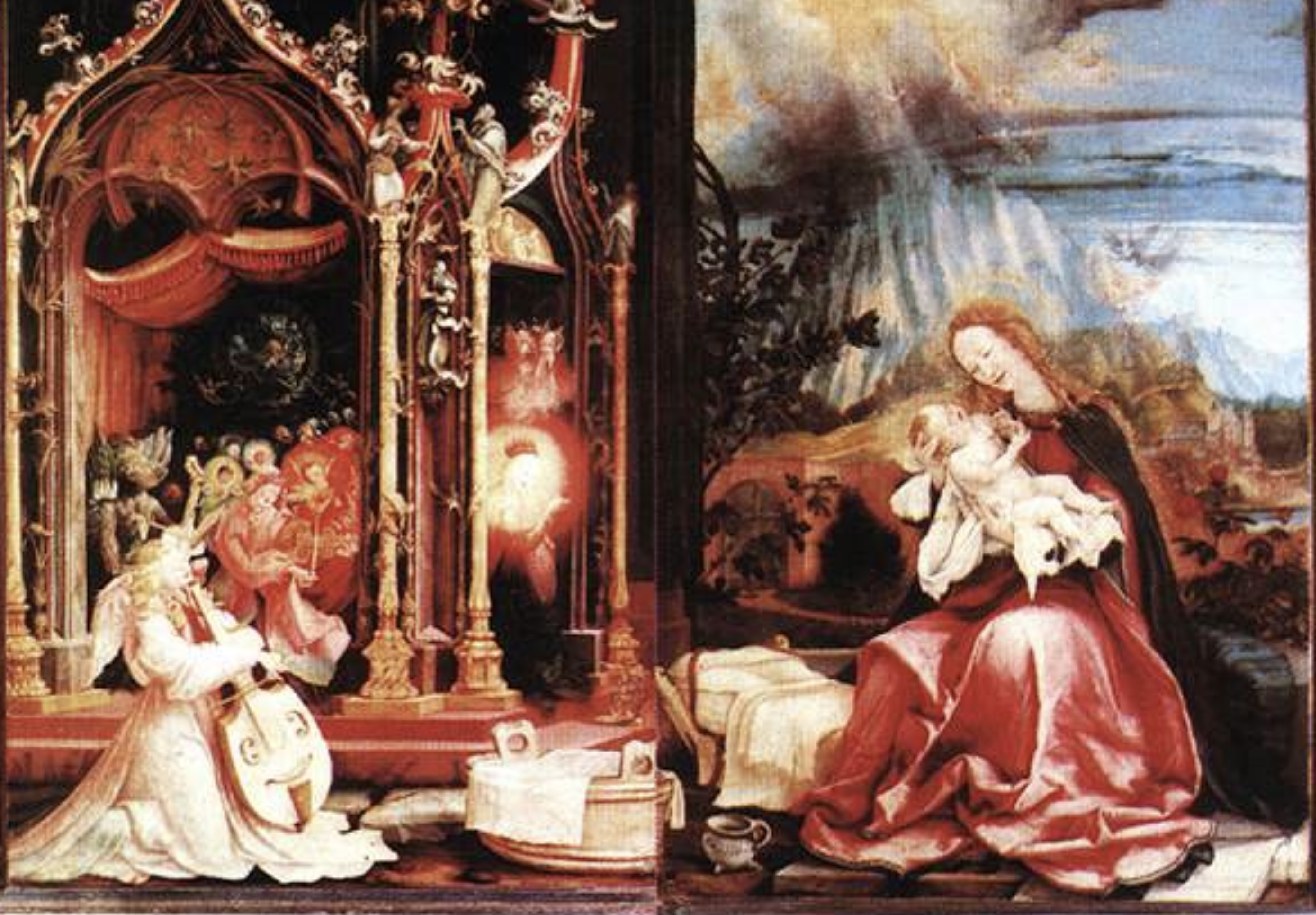

-Isenheim altar piece, 2nd view, Mathias Grünewald, 1512-1516, Unterlinden Museum at Colmar, Alsace, in France, painted for the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim near Colmar, which specialized in hospital work. The Antonine monks of the monastery were noted for their care of plague sufferers as well as their treatment of skin diseases, such as ergotism, aka St Anthony’s Fire. Ergotism sufferers endure spasms especially of the hands, legs, and feet. They also endure a dry gangrene. It is the result of fungus on cereal grains, which can still occur today; and, more recently, through ergoline-based drugs. The image of the crucified Christ is pitted with plague-type sores, showing patients that Jesus understood and shared their afflictions. The veracity of the work’s depictions of medical conditions was unusual in the history of European art. Please click on the image for greater detail.

Let all mortal flesh keep silence,

and with fear and trembling stand;

ponder nothing earthly-minded,

for with blessing in His hand,

Christ our God to earth descendeth,

our full homage to demand.

King of kings, yet born of Mary,

as of old on earth He stood,

Lord of lords, in human vesture,

in the body and the blood;

He will give to all the faithful

His own self for heavenly food.

Rank on rank the host of heaven

Spreads its vanguard on the way,

As the Light of light descendeth

From the realms of endless day,

Comes the powers of hell to vanquish

As the darkness clears away.

At His feet the six-winged seraph,

cherubim, with sleepless eye,

veil their faces to the presence,

as with ceaseless voice they cry:

Alleluia, Alleluia,

Alleluia, Lord Most High!

“”Christ our God to earth descendeth.” The Incarnation establishes a new presence of God among us. Jesus Christ, the eternal Son of the Father, comes to us as a little babe, wherein the “the fullness of God dwells bodily” (Col 2:9). On the one hand, God is already present everywhere, isn’t He? And on the other, the seraphim and cherubim do not “veil their faces to the presence” just everywhere. So what exactly is this new presence among us that evokes our “fear and trembling”?

Saint Thomas Aquinas describes God’s presence among creatures in a variety of ways (ST I, q. 8, a. 3). First, He is omnipresent by His essence, presence, and power. God’s creative act, His knowledge of creatures, and His governance of the world touch all things, and because of this connection, God is present there. Without God’s presence in these ways, creatures would cease to exist. From the highest of the blessed in heaven to the lowest and most mundane dust of the earth, things exist only because God is willing to be close to us. Beyond this universal presence, God can make Himself present in special ways as well. To intellectual creatures, God can give Himself as an object of our knowing and loving. That is to say, by pouring faith and charity into our hearts, God makes Himself present in us, dwelling in us as in a temple. 1 Cor 6:19.

There is another kind of presence of God, to which the angels veil their faces in homage and adoration. This presence is not merely by causation, or even the sublime gift of divine indwelling. The personal being of the Son unites to Himself a human nature, so that the man Jesus does not just possess grace to an eminent degree; rather, Jesus is truly God. The King of kings and Lord of lords Himself comes to us, taking on a human nature. The infant in the manger is not merely a sign of God’s presence. Jesus is God, the Incarnate Word.”

Love,

Matthew