-by David Warren

“As Christ was stripped of his garments, so the altars are stripped of their coverings in the traditional Maundy Thursday celebration. “They parted my garments amongst them: and upon my vesture they cast lots.” (Ps 22:18) Following hard upon this antiphon is the recitation of Psalm XXI (or, 22), the Deus meus: “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”…”

-written 1086 AD, in both Irish Gaelic & Latin. The first and last line of each verse are in Latin, while the middle lines are in Irish (Gaelic). Written by the Donegal monk Maol Iosa O Brolchain.

Deus meus adiuva me

Tabhair dom do shearch,a Mhic ghil Dé

Tabhair dom do shearch,a Mhic ghil Dé

Deus meus adiuva me.

In meum cor, ut sanum sit,

Tabhair, a Rí rán, do ghrá go grip;

Tabhair, a Rí rán, do ghrá go grip,

In meum cor, ut sanum sit.

Domine da quod peto a te,

Tabhair dom go dian a ghrian ghlan ghlé,

Tabhair dom go dian a ghrian ghlan ghlé,

Domine da quod peto a te.

Hanc spero rem et quaero quam,

Do shearc dom sonn, do shearc dom thall;

Do shearc dom sonn, do shearc dom thall,

Hanc spero rem et quaero quam.

Tuum amorem, sicut vis,

Tabhair dom go tréan, a déarfad arís;

Tabhair dom go tréan, a déarfad arís,

Tuum amorem, sicut vis.

Quaero, postulo, peto a te,

Mo bheatha i neamh, a mhic dhil Dé;

Mo bheatha i neamh, a mhic dhil Dé,

Quaero, postulo, peto a te.

Domine, Domine, exaudi me,

M’anam bheith lán de d’ghrá, a Dhé,

M’anam bheith lán de d’ghrá, a Dhé,

Domine, Domine exaudi me.

Rough translation

My God, help me.

Give to me Your love,

O son of my God

Into my heart/soul, that it be healthy

Give, O noble king, Your love swiftly

Lord, give what I beg of You

Give, give swiftly, O clear bright sun

This thing I hope and which I seek

Your love to me in this world, Your love to me in the next world

Give me your love, as fully as You wish.

Give me strongly what I ask of You again.

I search, I desire, I beg of You

My life in heaven, dear Son of God

My God, hear me

My soul may (it) be full of love, O God

“…It is an arresting Psalm, with its shockingly exact prevision of the Crucifixion, centuries before the event took place. It was very much in my thoughts, about the time I “lost my faith” in Atheism, some forty-one years ago while crossing a footbridge in London, England – curiously enough on a Maundy Thursday.

On the first anniversary of that event, or more precisely, the next Maundy Thursday, I found myself in Saint Ives, Cornwall, with the great studio potter, Bernard Leach, then approaching his ninetieth birthday. (I, approaching my twenty-fourth.) He was a Baha’i, deeply committed to the marriage of East and West. Much of our conversation, which went on through Easter, was about “art,” about “religion,” and about “art and religion.”

Strangely, for a man who had fallen away from his Christian upbringing, he decried the loss of Christian belief in modern England, including particularly faith in the literal Resurrection of Jesus Christ. While saying this, he began reciting passages from that Psalm, dwelling with special emphasis on, “The assembly of the wicked have inclosed me. They pierced my hands and my feet.”

Now, in the teaching of Baha’u’llah, as Leach understood it, the New Testament is factually correct, and moreover, anyone who faithfully follows Christ’s teachings is ipso facto a Baha’i. This is not my understanding, but we will let it pass. I was struck by the sudden bold defense of Christian belief, from a most unlikely source.

“Without faith,” Leach argued, “art is a monkey’s game.” Conversely, I supposed, without art, religious ideas cannot be adequately expressed. This can be seen in all cultures: this departure from the commonplace, in the midst of the commonplace. Everywhere the divine is instinctively acknowledged in elevated language, and gesture. Liturgy – art – is essential to it.

It is more than mnemonic; the Last Supper itself is not merely “remembered” in the liturgical events of the Triduum, or in the repetitions of the daily Mass. As the Catholic Church has continued to teach, the Real Presence transcends the historical event. Yet the historical event remains true within it. These things really happened; and by their nature continue to happen in a world that was altered by the coming of Our Savior.

They remain true even if the truth is rejected, as it was in Christ’s time, is, and will be. We do not have “progress” in the profane sense; we do not have a progressive revelation. We have the truth of Christ, at the center of history and of our being, now and forever. He is what lifts us out of our mundane sinful lives, and conducts our attention to what is changeless, pure, and in every sense, higher. We return to this, or try to get away.

To escape: into a world of our own making, and into a life where in our vanity we think that we can make the rules. Hell, which is discernible from Earth, is the putting of the greatest possible distance between ourselves and God. It is the reason Pride is the queen bee in the hive of the deadly sins; and in humility, Love becomes its opposite, theological virtue. It is the reason Love is expressed in acts of holy obedience, as we are resplendently told in the Magnificat. The return, to truth, begins in the acceptance of God’s will, even in denial of our own.

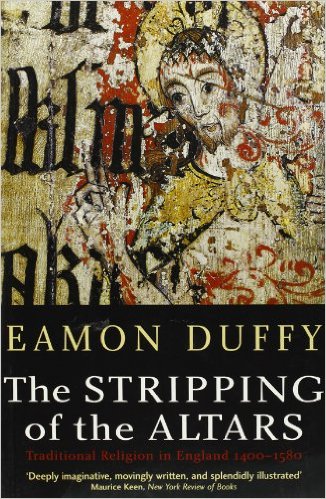

“The Stripping of the Altars” was used as the title of a book by Eamon Duffy, which has now been in circulation for a quarter century. It is a remarkable revisionist history of the English Reformation, which to my mind has grown in significance over this time. It challenges the myth and propaganda that has guided our thinking in the English-speaking realms, and beyond them wherever our influence has been felt.

It is a variation, I think, on the pagan myth of Prometheus, who stole the divine fire, and put it at the service of his fellow man. In our variation, we have believed that the Catholic Church was tired and failing through the generations prior to a kind of “liberation”; that the Protestant faith emerged as a rekindling, a maturing, a coming of age in a spiritual Magna Carta. Henceforth we would no longer be captive to the authority of a dark and conniving priesthood, but free – to read the Scriptures for ourselves, to strip the churches of their encrusted decorations; to form our own judgments, and write our own prayers.

We all share in this history, going back to Henry VIII, and striding forward through the reigns of Edward VI and Elizabeth I, when the medieval order was turned upside down, and the Catholic faith made capitally illegal. What Duffy showed, for this generation, as for instance Philip Hughes for an earlier one (in the three volumes of his Reformation in England, 1950 and 1963), was the evidence proving a huge, enduring, historical lie.

The old order was robust to the eve of this revolution, which was imposed by force. The resistance to it from the people was profound; yet it failed – in England as elsewhere – under the violence of an emerging political power, directing theology to its own ends. Liturgical destruction at every level, extending to the dissolution of monasteries, the smashing of images, the torching of medieval libraries – was necessary to the creation of a brave new world in which the Church was placed at the disposal of Caesar.

Yet all this is also prefigured, in the Psalm, and in Maundy Thursday’s stripping of the altars.”

Blessed Holy Thursday,

Matthew