-by Jacob Lupfer, a Methodist who admires the Catholic Church.

“Most people following this month’s Synod of Bishops on the Family in Rome are aware that the specter of allowing divorced and remarried Catholics to receive Communion is the most controversial and difficult issue among many controversial issues being discussed.

I have followed reports from the Synod closely and have been very interested in Catholic perspectives on divorce, remarriage, and the sacraments. As a divorced and remarried person with an abiding respect for Catholicism, I suppose I am more interested than most. Few Protestants believe that remarried persons are unworthy to receive Communion. Many Protestants are wondering, “What’s the big deal?” A few have asked for help in understanding the debate. I hope to helpfully to offer some explanation here.

The puzzled Protestant must first consider Catholic teaching on marriage. For one thing, marriage is a sacrament (one of seven, whereas Protestants have only two – baptism and the Lord’s Supper). As an efficacious sign of grace, a man and a woman, after giving consent, mutually confer the sacrament upon one another in the presence of the Church. It is not the work of a priest or a church or a civil magistrate. And, following words attributed to Jesus himself, marriage is indissoluble: “What God hath joined together let no man put asunder.”

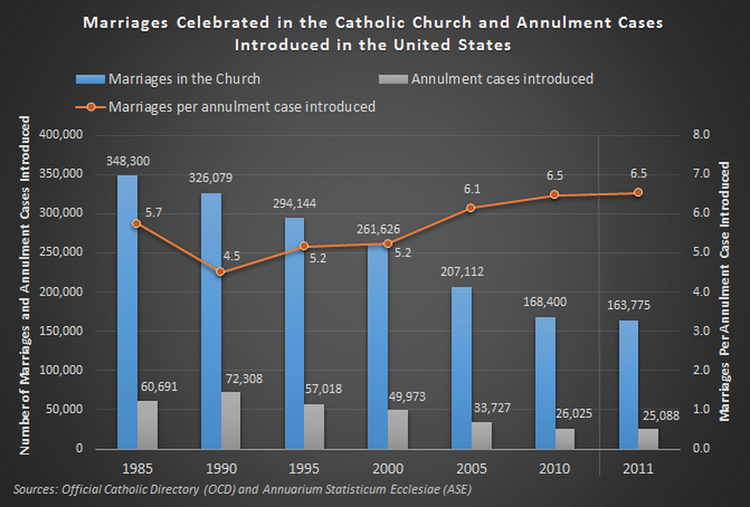

The next difference concerns divorce. Protestants typically assume that if a court grants a divorce, then the marriage no longer exists. In Catholicism, civil divorce is a mostly meaningless distinction. Church tribunals can grant annulments, which decree that the marriage was invalid. In recent generations, especially in territories like the U.S. where courts came to easily grant divorces, the standards for receiving an annulment have liberalized. (Though fewer U.S. Catholics are marrying, marrying in the Church, and seeking annulments.) Without an annulment, the Church considers the couple married as long as both spouses are still living. No action of a civil court can change that reality.

Georgetown’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate has complied some helpful data on marriage, divorce, and annulments.

Here is where it becomes complicated regarding Communion. A civilly remarried Catholic is, in the eyes of the Church, living in adulterous relationship. Every sex act with the new spouse is considered a mortal sin. Whereas Protestants came to accept subsequent marriages and stepfamilies without much trouble, the Catholic Church considers these situations “irregular” and maintains that without an annulment, the initial marriage remains intact. A civilly remarried Catholic could receive Communion if s/he is celibate. In Protestant churches, it would be virtually inconceivable for a pastor to confront remarried people about receiving Communion. But this gets to two more differences: fitness for receiving Communion and the nature of Communion itself.

In the United Methodist Church of my childhood, the minister invited everyone to the Lord’s Table, saying, “Ye that do truly and earnestly repent of your sins, and are in love and charity with your neighbors, and intend to lead a new life, following the commandments of God, and walking from henceforth in his holy ways: Draw near with faith and take this holy sacrament to your comfort.” Over time, the language of intentionality was shortened and arguably watered down a bit. The most frequently used UMC Communion ritual now says, “Christ our Lord invites to his table all who love him, who earnestly repent of their sin and seek to live in peace with one another…” Regardless of denomination, the invitation is relatively simple for Protestants: If you repent, you are welcome to partake. In true Protestant fashion, you are competent to determine for yourself your fitness to receive the sacrament. You and God know your heart. No priest or catechism is necessary to assist in that determination!

Not so in Catholicism. You cannot say, “Well, I am in good conscience, being happily and faithfully remarried.” Furthermore, if you receive Communion in a state of grave sin, you commit another grave sin.

A final significant difference between Protestants and Catholics on this question concerns the nature of Communion itself. Most Protestants suppose that the major Christian debates about Communion concern the frequency with which it is celebrated and the mode by which it is received. But this obscures a greater, more fundamental difference. For Protestants, Communion is a community meal, a moment of personal devotion, and a remembrance of Jesus himself. For Catholics, it is Jesus himself. Christians differ about how exactly Christ is present in the bread and wine. Liturgical Protestants hold that Communion is more than a remembrance. But for Catholics, through transsubstiantation, the elements become the actual body and blood of Christ.

With an arguably “higher” view of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, Catholics take more seriously the idea that communicants must receive Him worthily. For the civilly remarried Catholic, this is apparently impossible without changes in Church doctrine.

In convening the Synod of Bishops, Pope Francis deliberately sought a diversity of views. Some theologians, most prominently Cardinal Walter Kasper, have argued that civilly remarried Catholics be allowed to receive Communion. The most vocal opponents have been Cardinal George Pell and Cardinal Raymond Burke. Their Eminences have engaged in a spirited and sometimes pointed public debate. Based on reports of the Synod’s first week, there seems to be an openness to pastoral innovation, but there is no sign that bishops want the Church to abandon its belief in the indissolubility of marriage.

Unsurprisingly, many lay Catholics have also weighed in on the question. Since Protestants will instinctively be sympathetic to the view that remarried people should be permitted to receive Communion, I will highlight two traditionalists. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has a characteristically thoughtful blog post that includes links to his other writings on this and related issues. In a provocative column, civilly remarried laywoman Louise Mensch states: “I am a divorced Catholic. And I’m sure it would be a mortal sin for me to take Communion.” Her perspective gives expression to the Church’s sense that Catholics in irregular relationships should attend Mass and remain part of parish communities even though they cannot receive Communion.

Protestants who wish to understand why it’s a big deal for Catholics to even debate the idea that remarried people can receive Communion, must bear in mind these vital differences:

- Marriage as a sacrament vs. ‘merely’ a God-ordained union

- Sacramental marriage vs. civil marriage

- Annulments vs. divorce

- Clerical/Church determination vs. individual determination of worthiness to receive Communion

- “Real presence” as real presence vs. “Real presence” as holy mystery or ‘mere’ remembrance

Regardless of your position, Protestants should take note of the Synod’s consideration of how the Church can nurture marriage and family life. The challenges the pope hopes to address are not uniquely Catholic problems.”

Love,

Matthew