Not a beatus, but it may, I say, I think, just a suspicion, just may, come as little surprise I have a THING for clerical scientists & engineers. Just may. 🙂 AND, he’s Irish, so part of the tribe, which doesn’t hurt either, now does it? 🙂

You say “Fides et Ratio“; I blithely, coyly put my face in my hands, drum my fingers on my temples, smile, and respond, “I LOVE IT when you talk NERDY to me! 🙂

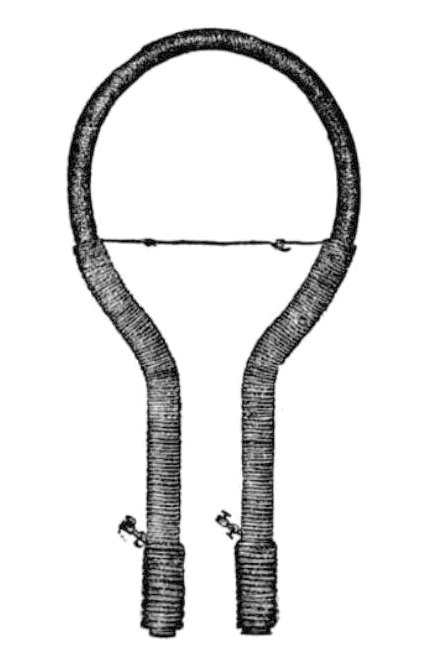

The Induction Coil

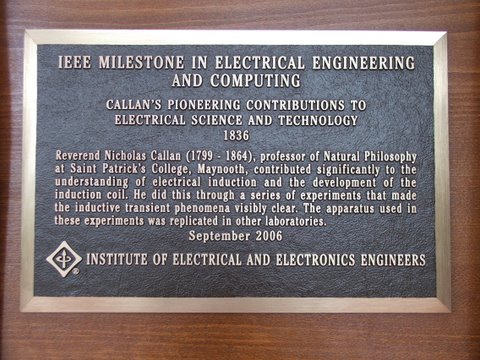

Influenced by William Sturgeon and Michael Faraday, Callan began work on the idea of the induction coil in 1834. He invented the first induction coil in 1836.

An induction coil produces an intermittent high-voltage alternating current from a low-voltage direct current supply. It has a primary coil consisting of a few turns of thick wire wound around an iron core and subjected to a low voltage (usually from a battery). Wound on top of this is a secondary coil made up of many turns of thin wire. An iron armature and make-and-break mechanism repeatedly interrupts the current to the primary coil, producing a high-voltage, rapidly alternating current in the secondary circuit.

Induction coils were used by Hertz to demonstrate the existence of electromagnetic waves, as predicted by James Maxwell and by Lodge and Marconi in the first research into radio waves. THANK FR CALLAN FOR YOUR CELL PHONE!!!! Their largest industrial use was probably in early wireless telegraphy spark-gap radio transmitters and to power early cold cathode x-ray tubes from the 1890s to the 1920s, after which they were supplanted in both these applications by AC transformers and vacuum tubes. THANK FR CALLAN FOR YOUR COMPUTER, GPS, & VIDEO GAMES!!! However their largest use was as the ignition coil or spark coil in the ignition system of internal combustion engines, where they are still used, although the interrupter contacts are now replaced by solid state switches. THANK FR CALLAN YOU CAN DRIVE A CAR!!!! A smaller version is used to trigger the flash tubes used in cameras and strobe lights.

Callan invented the induction coil because he needed to generate a higher level of electricity than currently available. He took a bar of soft iron, about 2 feet (0.61 m) long, and wrapped it around with two lengths of copper wire, each about 200 feet (61 m) long.

Callan connected the beginning of the first coil to the beginning of the second. Finally, he connected a battery, much smaller than the enormous contrivance just described, to the beginning and end of winding one. He found that when the battery contact was broken, a shock could be felt between the first terminal of the first coil and the second terminal of the second coil.

Further experimentation showed how the coil device could bring the shock from a small battery up the strength level of a big battery. So, Callan tried making a bigger coil. With a battery of only 14 seven-inch (178 mm) plates, the device produced power enough for an electric shock “so strong that a person who took it felt the effects of it for several days.” NEXT!!! “For your penance…!!!” Yikes!!!! Callan thought of his creation as a kind of electromagnet; but what he actually made was a primitive induction transformer.

Callan’s induction coil also used an interrupter that consisted of a rocking wire that repeatedly dipped into a small cup of mercury (similar to the interrupters used by Charles Page). Because of the action of the interrupter, which could make and break the current going into the coil, he called his device the “repeater.” Actually, this device was the world’s first transformer. Callan had induced a high voltage in the second wire, starting with a low voltage in the adjacent first wire. And the faster he interrupted the current, the bigger the spark. In 1837 he produced his giant induction machine: using a mechanism from a clock to interrupt the current 20 times a second, it generated 15-inch (380 mm) sparks, an estimated 60,000 volts and the largest artificial bolt of electricity then seen.

The ‘Maynooth Battery’ and other inventions

Callan experimented with designing batteries after he found the models available to him at the time to be insufficient for research in electromagnetism. The Year-book of Facts in Science and Art, published in 1849, has an article titled “The Maynooth Battery” which begins “We noticed this new and cheap Voltaic Battery in the Year-book of Facts, 1848, p. 14,5. The inventor, the Rev. D. Callan, Professor of Natural Philosophy in Maynooth College, has communicated to the Philosophical Magazine, No. 219, some additional experiments, comparing the power of a cast-iron (or Maynooth) battery with that of a Grove’s of equal size.” Some previous batteries had used rare metals such as platinum or unresponsive materials like carbon and zinc.

Callan found that he could use inexpensive cast-iron instead of platinum or carbon. For his Maynooth battery he used iron casting for the outer casing and placed a zinc plate was immersed in a porous pot (pot that had an inside and outside chamber for holding two different types of acid) in the centre. In the single fluid cell he disposed of the porous pot and two different fluids. He was able to build a battery with just a single solution.

While experimenting with batteries, Callan also built the world’s largest battery at that time. To construct this battery, he joined together 577 individual batteries (“cells”), which used over 30 gallons of acid. Since instruments for measuring current or voltages had not yet been invented, Callan measured the strength of a battery by measuring how much weight his electromagnet could lift when powered by the battery. Using his giant battery, Callan’s electromagnet lifted 2 tons. The Maynooth battery went into commercial production in London. Callan also discovered an early form of galvanisation to protect iron from rusting when he was experimenting on battery design, and he patented the idea.[9]

He died in 1864 and is buried in the cemetery in St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth.

Honors

The Callan Building on the north campus of NUI Maynooth, a university which was part of St Patrick’s College until 1997, was named in his honour. In addition, Callan Hall in the south campus, was used through the 1990s for first year science lectures including experimental & mathematical physics, chemistry and biology. The Nicholas Callan Memorial Prize is an annual prize awarded to the best final year student in Experimental Physics.

Publications

Electricity and Galvanism (introductory textbook), 1832

IEEE

Scientifically yours,

Matthew