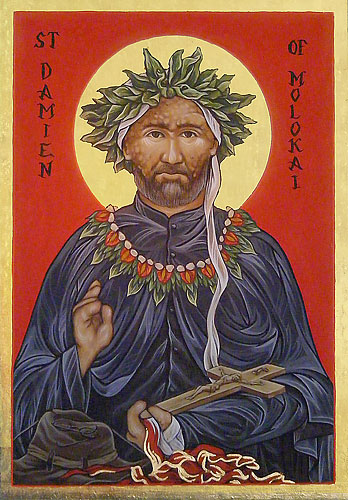

Born in Tremelo, Belgium, on January 3, 1840, the seventh child and fourth son of the Flemish corn merchant Joannes Franciscus (“Frans”) De Veuster and his wife Anne-Catherine (“Cato”) Wouters; following in the footsteps of his sisters Eugénie and Pauline (who became nuns) and brother Auguste, who became a priest of the same order, he joined the Sacred Hearts of Jesus & Mary Fathers, aka Picpus Fathers, in 1860. He was born Joseph and received the name Damien in religious life.

His superiors thought that he was not a good candidate for the priesthood because he lacked education. However, he was not considered unintelligent. Because he learned Latin well from his brother, his superiors decided to allow him to become a priest. During his ecclesiastical studies, he would pray every day before a picture of St. Francis Xavier, SJ, patron of missionaries, to be sent on a mission. When his brother became ill and could not be sent on a mission to Hawaii, Damien went in his place.

In 1864, he was sent to Honolulu, Hawaii, where he was ordained. For the next nine years he worked in missions on the big island, Hawaii. In 1873, he went to the leper colony on Molokai, after volunteering for the assignment.

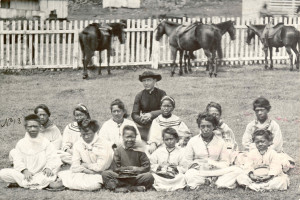

Hawaiians who contracted the disease were forcibly deported to Molokai under government sanctioned quarantine. Dumped like so much trash, to live or to die, inconsequential, as fate may determine. Damien cared for lepers of all ages, but was particularly concerned about the children segregated in the colony.

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is a chronic infection caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis. Initially infections are without symptoms and typically remain this way for 5 to as long as 20 years. Symptoms that develop include granulomas of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes.

This may result in a lack of ability to feel pain and thus loss of parts of extremities due to repeated injuries. Weakness and poor eyesight may also be present. It is believed to be transmitted by respiratory droplets. It is not very contagious, 95% of humans are immune to the disease, but this was not known before recently.

You have to be up close and personal for an extended period of time to contract the disease, such as a priest might be in the care of his flock; the unwanted, the abandoned, the diseased, the repulsive to look at, the impossible to touch. Literally, “untouchables”.

Kalaupapa and Kalawao, where the leper colonies were located, is on the eastern end of the Kalaupapa peninsula on the island of Molokaʻi. Kalawao County, where the villages are located, is divided from the rest of Molokaʻi by a steep mountain ridge, and even now the only land access to it is by a mule trail. About 8,000 Hawaiians were sent to the Kalaupapa peninsula from 1866 through 1969.

Father Damien announced he was a leper in 1885 and continued to build hospitals, clinics, and churches, and some six hundred coffins. He dressed ulcers, built homes and furniture, made coffins, and dug graves. Before his arrival, a hopeless people were descending into a hell of hopelessness, in drunkenness and lewd conduct. Under his leadership, basic laws were enforced, shacks became painted houses, working farms were organized, and schools were established.

He died on 8am, April 15 , 1889, at the age of 49.

Hawaiian King David Kalākaua bestowed on Damien the honor “Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua”. When Princess Lydia Liliʻuokalani visited the settlement to present the medal, she was reported as having been too distraught and heartbroken to read her speech.

The most well-known treatise against Damien was by a Honolulu Presbyterian, Reverend Charles McEwen Hyde, in a letter dated August 2, 1889, to a fellow pastor, Reverend H. B. Gage; in it, Hyde referred to Father Damien as “a coarse, dirty man” whose leprosy should be attributed to his “carelessness”.

In 1889, Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson and his family arrived in Hawaii for an extended stay. While there Stevenson, also a Presbyterian, drafted a famous open letter as a rebuttal in defense of Damien.

Prior to writing his letter, dated February 25, 1890, Stevenson stayed on Molokaʻi for eight days and seven nights, during which he kept a diary. In the letter Stevenson answered Hyde’s criticisms point by point. He sought testimony from critical Protestants who knew the man, which he recorded in his diary. The treatise included some extracts, like the following, which upbraided Rev. Hyde for his fault finding:

“But, sir, when we have failed, and another has succeeded; when we have stood by, and another has stepped in; when we sit and grow bulky in our charming mansions, and a plain, uncouth peasant steps into the battle, under the eyes of God, and succors the afflicted, and consoles the dying, and is himself afflicted in his turn, and dies upon the field of honor – the battle cannot be retrieved as your unhappy irritation has suggested. It is a lost battle, and lost for ever. One thing remained to you in your defeat – some rags of common honor; and these you have made haste to cast away.”

“Not without fear and loathing,” Pope Benedict underlined, “Father Damian made the choice to go on the island of Molokai in the service of lepers who were there, abandoned by all. So he exposed himself to the disease of which they suffered. With them he felt at home. The servant of the Word became a suffering servant, leper with the lepers, during the last four years of his life.”

He continued, “To follow Christ, Father Damian not only left his homeland, but has also staked his health so he, as the word of Jesus announced in today’s Gospel tells us, received eternal life.”

The figure of Father Damian, Benedict XVI added, “teaches us to choose the good fight not those that lead to division, but those that gather us together in unity.”

In Saint Damien’s role as the unofficial patron of those with HIV and AIDS, the world’s only Roman Catholic memorial chapel to those who have died of this disease, at the Église Saint-Pierre-Apôtre in Montreal, Quebec, is consecrated to him.

“I make myself a leper with the lepers to gain all to Jesus Christ.”

-St Damien de Veuster, SSCC

“Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament is the most tender of friends with souls who seek to please Him. His goodness knows how to proportion itself to the smallest of His creatures as to the greatest of them. Be not afraid then in your solitary conversations, to tell Him of your miseries, fears, worries, of those who are dear to you, of your projects, and of your hopes. Do so with confidence and with an open heart.”

–St. Damien of Molokai

“The Eucharist is the bread that gives strength… It is at once the most eloquent proof of His love and the most powerful means of fostering His love in us. He gives Himself every day so that our hearts as burning coals may set afire the hearts of the faithful.”

— St. Damien of Molokai

Love,

Matthew