Letter to Cardinal George of Chicago:

6/12/2011

Dear Cardinal George,

Hello, my name is Amy Goggin and I am a parishioner at St. John Fisher in Chicago. I’m writing this letter to you to ask for your support and guidance in a cause that has been on my heart recently. I have an on-line store. I make rosaries and religious jewelry. I have wanted to make a chaplet/bracelet for people afflicted with Down’s syndrome. While researching the patron Saint for these individuals, I realized that there is no patron Saint for them. I am wondering how to go about declaring one? How does the Church declare a patron saint?

I understand that there are patron saints for people with mental illnesses and people that are handicapped in one form or another but, there needs to be a specific advocate in heaven for the growing number of people afflicted with Down’s syndrome. Prenatal screening and diagnostic testing is most often used to identify unborn babies with Down’s syndrome and then that information is used to encourage an abortion. This testing does not provide information that could be used to treat the baby before birth. One out of every 800 pregnancies is diagnosed with having a Down’s baby.

That is about 400,000 in the US alone. Out of those, 84% to 91% are aborted in the US. If a mother decides to have her Down’s syndrome child there are many medical complications that are awaiting the child throughout his/her life. There seems to be a cultural war against these innocent human beings right from the start. Due to the large number of people with this condition and the life-threatening situation they find themselves, we as Catholics need an advocate in Heaven to offer up our prayers of both petition and thanksgiving.

While researching a saint that would be appropriate for this cause, I found Servant of God (whose cause for canonization was opened in 2007): Dr. Jerome Lejeune. He was a French Doctor that spent his life trying to find a cure for Down’s syndrome and fighting for an awareness of the sanctity of their lives. He discovered the cause of Down’s syndrome in 1958.

Dr. Lejeune worked closely with Pope John Paul II and was appointed the first president of the Pontifical Academy for Life. He treated around 5,000 patients. He would explain to new mothers that their child’s name was (child’s name) and he/she is not a disease, but a person that happens to have a disease. His mission was to have others understand the dignity that these individuals possessed, by looking beyond their condition to see a human being. His own daughter, Clara Lejeune Gaymard wrote a memoir titled Life is a Blessing about her father .

I believe that due to the nature of Dr. Lejeune’s life’s work, he is the perfect patron saint for people afflicted with this genetic condition. I’m wondering if you can help us with three things by your guidance and blessing. My friends and I are willing to do whatever we have to do, we just need some direction and support. We want to know how to officially request that the Church declare Lejeune the patron saint for people afflicted with Down’s syndrome.

We want to know how to create a chaplet of prayers for his intercession. Finally, there is a strong local support to have a national shrine on the South Side of Chicago for Catholics to come and pray for Lejeune’s intercession for their loved ones with Down’s syndrome. We believe that because of the large population of individuals with this condition on the South Side of Chicago, this would be the most appropriate place for such a shrine. We are willing to take on any logistical legwork necessary to further this cause. I would appreciate any help you can offer my friends and I with this endeavor and look forward to hearing back from you soon.”

Jerome Lejeune was born in Montrouge, France, in 1926. A reading of The Country Doctor by the French novelist Balzac convinced him of his vocation when he was 13 years old. He too wanted to be a simple country doctor dedicating his life to helping the poor.

After attending medical school, he was persuaded by Professor Raymond Turpin to collaborate with him on a study of Down syndrome. He accepted this challenge and his dreams of being a simple country doctor were laid to rest.

He and his wife Birthe had five children and his family life and his faith were always his priority. When his beloved father was dying of lung cancer, he recognised more deeply the mystery of human suffering and the presence of Christ in all those who suffer.

In 1954, he was appointed a committee member of the French Genetics society and in 1957 was named an expert on the effects of atomic radiation on human genetics by the United Nations.

In 1959 he discovered the cause of Down syndrome and was also to diagnose the first case of Cri du Chat Syndrome. In 1962, he was awarded the prestigious Kennedy prize and, in 1965, he was appointed to the first Chair in Fundamental Genetics at the University of Paris. During this time, he helped thousands of parents to accept and love their children with Down syndrome.

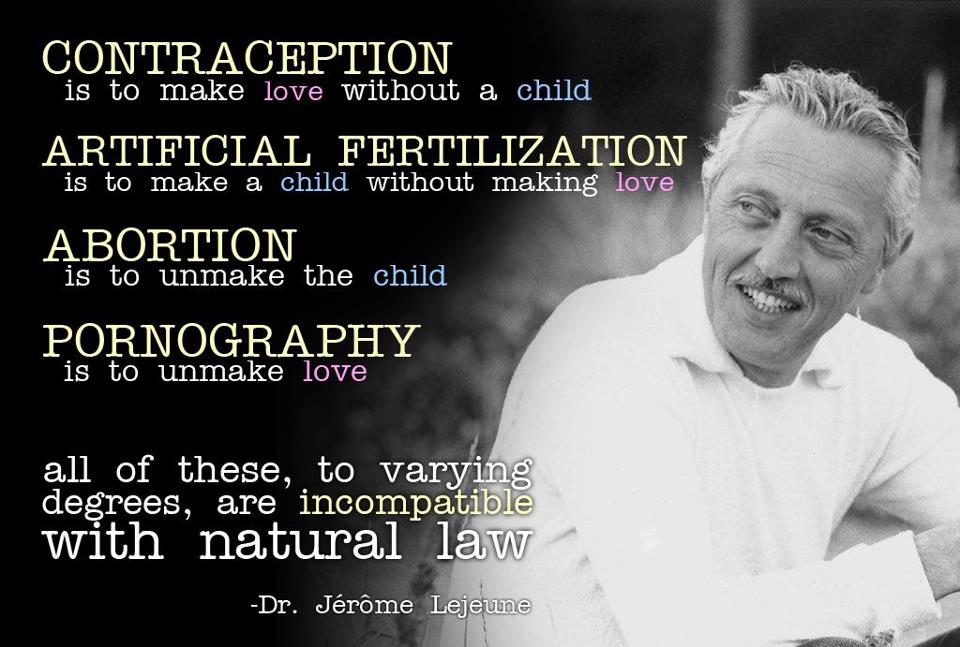

-quote of Dr. Jerome Lejeune, MD, in a letter to his wife after his acceptance speech in 1969 when he was given the William Allan Memorial Award, the highest distinction that could be granted to a Geneticist, in which he strenuously condemned abortion.

In 1991, he wrote a summary of his reflections on medical ethics for his fellow Catholics in seven brief points:

1. Christians, be not afraid. It is you who possess the truth. Not that you invented it but because you are the vehicle for it. To all doctors, you must repeat: “you must conquer the illness, not attack the patient.”

2. We are made in the image of God. For this reason alone all human beings must be respected.

3. Abortion and infanticide are unspeakable crimes.

4. Objective morality exists. It is clear and it is universal – because it is Catholic.

5. The child is not disposable and marriage is indissoluble.

6. “You shall honour your father and mother.” Therefore, uniparental reproduction by any means is always wrong.

7. In so-called pluralistic societies, they shout it down our throats: “You Christians do not have the right to impose your morality on others.” Well, I tell you, not only do you have the right to try to incorporate your morality in the law but it is your democratic duty.

There is a famous story of an American physician who told Lejeune the following:

“My father was a Jewish physician in Braunau, Austria. One day only two babies were born at the local hospital. The parents of the healthy boy were proud and happy. The other was a girl (with Down syndrome) and her parents were sad.”

The physician ended the story by saying that the girl grew up to look after her mother despite her own disability. Her name is not known. The boy’s name was Adolph Hitler. Quite likely the story is apocryphal. However, it does express the truth that was central to Lejeune’s vocation: people with disabilities are certainly no less human than those without.

In 1993, Pope Saint John Paul II, his close friend, appointed Lejeune to be the first president of the Pontifical Academy for Life. That same year he was diagnosed with lung cancer and, by Good Friday of 1994, he was critically ill. “I have never betrayed my faith” he said. While reflecting on his patients, he was moved to tears and said: “I was supposed to have cured them…What will happen to them?”

A little later he was filled with joy. He said: “My children, if I can leave you with one message, this is the most important of all: We are in the hands of God. I have experienced this numbers of times.” He died the next day. Pope Saint John Paul II wrote of him: “We find ourselves today faced with the death of a great Christian of the twentieth century, a man for whom the defense of life had become an apostolate.” His cause for canonization has been postulated. Our bishops have recently agreed on three priorities for the Church, one of which is to proclaim the coming of the Kingdom by supporting integrity in public life, cohesion and mutual respect in society and serving the marginalized and the vulnerable. May this great servant of God, an apostle of the vulnerable, be an example to us all.

Prayer to Obtain Graces by God’s Servant’s Intercession

God, who created man in your image and intended him to share your glory, we thank you for having granted to your Church the gift of professor & doctor, Jerome Lejeune, MD, a distinguished Servant of Life. He knew how to place his immense intelligence and deep faith at the service of the defense of human life, especially unborn life, always seeking to treat and to cure.

A passionate witness to truth and charity, he knew how to reconcile faith and reason in the sight of today’s world. By his intercession, and according to Your will, we ask You to grant us the graces we implore, hoping that he will soon become one of your saints.

Amen.

Venerable Servant of Life!!!! Dr. Jerome Lejeune, MD, pray for us!!!!

Love,

Matthew

UPDATE: On January 21, 2021 Pope Francis authorized the Congregation for the Causes of Saints to promulgate a decree concerning the heroic virtues of Lejeune. He now will be referred to as Venerable Jérôme Lejeune.

Aude Dugast is the Paris-based postulator of the cause of canonization of Jérôme Lejeune. Dugast did not know Lejeune personally, though she admitted that he might have spoken at her university when she was growing up in Paris. She went to work at the Jérôme Lejeune Foundation in the French capital, then becoming vice postulator of the sainthood cause in 2007 and postulator in 2012. She oversaw the examination of his writings and coordinated the taking of testimony by those who knew him. Finally, she wrote the positio, a 1,000-page document detailing Lejeune’s life and virtues in support of his canonization.

“For me the main thing is his faith and his charity — a very strong and beautiful faith,” she said. “He never had doubts. He was a famous scientist, a genius, but he never saw any conflict between faith and science. Science helped him know creation, and faith helped him understand creation and to understand God. He showed there is no contradiction between these two kinds of knowledge.”

The profession in which Lejeune worked very often would pit intelligence against faith, but “he was the opposite,” Dugast said.

His other strong quality was his “incredible charity,” she attested. “He loved his patients. There were so many mothers who said they were very moved when they met him the first time and Lejeune looked at their son or daughter, and they saw that he looked at them with so much love in their eyes that they were very surprised, because he was a very famous professor. They were afraid to come with their child to this hospital, … but it was the first time they saw someone who was full of love for the child, and each time it was a new start for the family.”

He stood with science

Lejeune was born in 1926 in the Paris suburb of Montrouge. He studied medicine, then became a researcher at the National Center for Scientific Research in 1952. In July 1958, assisted by Marthe Gautier, he established a link between a state of mental debility and a chromosomal aberration, by the presence of an extra chromosome on the 21st pair, thus discovering trisomy 21.

This caused a revolution in the thinking of the time. As Jason Jones and John Zmirak have written, the families of Down syndrome children for decades had lived under a false moral stigma, since it was widely believed that the child’s “retardation” was the side-effect of syphilis in the mother, which was associated in the popular mind with prostitution.

“By offering rock-solid proof of a biological cause for Down syndrome, Lejeune helped the parents of such children move in from out of the shadows,” Jones and Zmirak wrote. But he didn’t stop there, as they documented:

Lejeune went on to uncover the genetic basis for another devastating birth defect, Cri-du-Chat Syndrome, and made advances in understanding the causes of Fragile-X Syndrome. He also anticipated the rest of medical science by decades in his insistence on the importance of folic acid in reducing the risk of many birth defects.

Dugast concluded, “I think this love for the patient is really the explanation of all his life.He could have worked on so many other subjects — math, physics — and sometimes he wanted to do that. He would write in his diary, ‘Every time I wanted to work on something else, I had a mother or a patient who told me, Professor, we need you to find a treatment.’ And so he always decided, ‘I can’t go away to other things, because my patients need me.’”

Prophet in his own profession

To his horror, Lejeune’s research began to be used for purposes he disapproved of, such as early detection of trisomy 21 in embryos, leading to their abortion. He decided to publicly defend Down children by fighting against abortion.

“He could do no other than defend his patients,” Dugast said. “He knew they can’t defend themselves.”

And this is where his living out the virtues in a heroic way — a key element in the Church’s decision on whether or not someone can be declared a saint — is so evident for Dugast. Lejeune could have quietly continued in his research and his treatment of patients, without participating in abortion himself. But he felt compelled to speak out, even at the risk of being shunned by the profession.

“The main example for me is when he went to San Francisco in 1969 to receive the Allan Award,” said Dugast, referring to the William Allan Memorial Award of the American Society of Human Genetics. The award ceremony would include a major speech by the recipient, and Lejeune knew that his audience would include “the most important geneticists in the world,” she said.

“He decided that day to say clearly that medicine had to decide if it wanted to kill or cure,” the postulator said. “He knew that in doing that he could lose everything. But he felt that maybe there was an opportunity for these geneticists to change their mind.”

In fact, it has been widely reported that Lejeune later told his wife, “Today, I lost my Nobel Prize in medicine.”

“It was very courageous, and for me it was really the first heroic decision, because he could have decided to be a very ethical physician, never do abortions or anything against his patients, but without talking, without saying anything, without having any program. But he knew he had to speak out. The danger for him was not to not do abortions, but to talk and to tell the truth.”

A year or two after the Allan lecture, it was evident that Lejeune had become almost a persona non grata.

“He didn’t get invitations to any scientific congresses,” Dugast said. “Before this he was the geneticist everyone wanted to invite.”

But he wasn’t totally out in the cold. Pope St. Paul VI appointed him to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1974. He was also a member of the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, and of the Academy of Medicine.

Appointed by Pope St. John Paul II in February 1994 to head the new Pontifical Academy for Life, Lejeune died two months later, on April 3, which was Easter Sunday that year.

Today the Jérôme Lejeune Foundation continues its work of care and research, in France, Spain and the United States.