We are creatures of conditioning and history. All human beings are and ever were…with the exception of One, through His Divine nature. This former part of this proposition is the antithesis of popular American thought. American thought implies all ideas, let alone people, are equal. It’s easier, much easier to think THAT. 🙁 We know the latter is factually untrue, other than politically, and it DOES make for delicious political philosophy. Thank you, TJ!!!! 🙂 What of the former?

Americans, like the empires before them, in the vacuum of their success, all believed they were right; morally, especially, but in all other ways, too, due to their success; a circular, self-affirming logic. For immediate relief, I propose a trip outside the country. There is another world. Really. Trust me. And, (gasp), they don’t think like us. And, they don’t see the world the way we do. Also, while abroad, catch some news on the BBC/Al Jazeera, and see what it is like to have a WORLD view.

If we dare to adjudicate the, as we perceive/see them, errors of our time, intellectual integrity requires we first critique our own biases and context for making such judgments. Otherwise, our conclusions bear no merit whatsoever.

First, some terms, gentle reader, to whet the appetite and salt the fare:

Can you smell the skepticism? The relativism? Can you taste it? It is in the wind, in the very air, that we breathe. A little sulfurous, no? Acrid? 🙂

“What is this thing? Called Love?

Modernism is a philosophical movement that, along with cultural trends and changes, arose from wide-scale and far-reaching transformations in Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the factors that shaped Modernism were the development of modern industrial societies and the rapid growth of cities, followed then by the horror of World War I. Modernism also rejected the certainty of Enlightenment thinking, and many modernists rejected religious belief.

Modernism, in general, includes the activities and creations of those who felt the traditional forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, philosophy, social organization, activities of daily life, and even the sciences, were becoming ill-fitted to their tasks and outdated in the new economic, social, and political environment of an emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound’s 1934 injunction to “Make it new!” was the touchstone of the movement’s approach towards what it saw as the now obsolete culture of the past. In this spirit, its innovations, like the stream-of-consciousness novel, atonal (or pantonal) and twelve-tone music, quantum physics, genetics, neuron networks, set theory, analytic philosophy, the moving-picture show, divisionist painting and abstract art, all had precursors in the 19th century.

A notable characteristic of Modernism is self-consciousness, which often led to experiments with form, along with the use of techniques that drew attention to the processes and materials used in creating a painting, poem, building, etc. Modernism explicitly rejected the ideology of realism and makes use of the works of the past by the employment of reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody.

Some commentators define Modernism as a mode of thinking—one or more philosophically defined characteristics, like self-consciousness or self-reference, that run across all the novelties in the arts and the disciplines. More common, especially in the West, are those who see it as a socially progressive trend of thought that affirms the power of human beings to create, improve and reshape their environment with the aid of practical experimentation, scientific knowledge, or technology. From this perspective, Modernism encouraged the re-examination of every aspect of existence, from commerce to philosophy, with the goal of finding that which was ‘holding back’ progress, and replacing it with new ways of reaching the same end. Others focus on Modernism as an aesthetic introspection. This facilitates consideration of specific reactions to the use of technology in the First World War, and anti-technological and nihilistic aspects of the works of diverse thinkers and artists spanning the period from Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) to Samuel Beckett (1906–1989).

Postmodernism is a late-20th-century movement in the arts, architecture, and criticism that was a departure from modernism. Postmodernism includes skeptical interpretations of culture, religon, literature, art, philosophy, history, economics, architecture, fiction, and literary criticism.

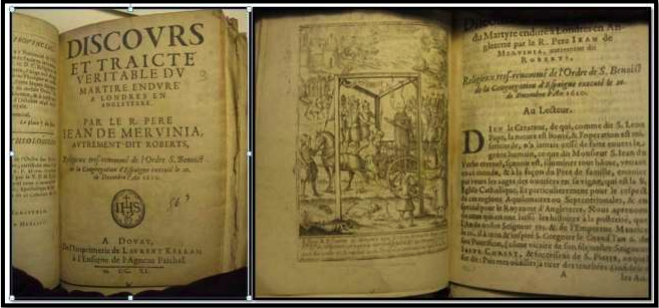

from http://nominalismdenounced.blogspot.com/ (Disclaimer: I DO NOT concur with the author’s overall positions, nor, hardly, conclusions, however, he makes SOME points well to support his arguments. Romans 5:20. Which I, in turn, use to make my own. I do accept responsibility, in general, for what I have quoted below from the author’s article. God help me, always.)

-by Joseph Andrew Settanni

“The advance of postmodernity, into the 21st century, has seen the full fruits of the results of the rabid pursuit of what had been regarded as modernity, often called the modern project, which includes abortion, artificial contraception, infanticide, euthanasia, sexually transmitted diseases, homosexuality, pornography, etc., meaning the vindication of human hubris.

The postmodern thrust is most clearly seen, therefore, in the expanding and intensifying worship of death, usually called the culture of death; the human race, denying the rights and existence of God, actively seeks self-extermination with its normally decreasing birthrates and increased sterility observed around the world; it is, thus, a manifestly manmade demographic nightmare nihilistically engulfing a much too willing humanity.

Of course, the cancerous roots of this profoundly spiritual crisis, meaning the nihilistic choosing of a completely intramundane-immanentist eschatology, go deep. What started as an intellectual tendency much earlier in the history of Western thought became first “codified” in philosophical terms by an aberrant English Franciscan Scholastic, William of Ockham or Occam (c. 1287–1347), with his subjectivist and relativist advocacy of nominalism, which, later in time, was also fairly called (appropriately enough) Occamism. And, as Richard M. Weaver had noted long ago, ideas have consequences. (Ed. Ask the victims of the Nazis, the Communists, the Khmer Rouge, if they do, fair reader?)

Admittedly, nominalism, which ultimately leads to nihilism, is very epistemologically seductive and even most of its adherents rarely, if ever, become conscious of its supremely thoroughgoing hold upon them.

For instance, the needed denunciation of the gigantic religious/theological heresy of Modernism, by Pope St. Pius X, would have been impossible to truly comprehend (as to the precise reason for the condemnation’s vital need) without the prior success of the development of the important intellectual error known as nominalism in cognition, for there is no greater deception than self-deception…(Ed. nor none more rampant, gentle reader.)

The Matter Itself Defined

But, what is nominalism? Simply put, it is the explicit denial of there being any universals; the doctrine that general ideas or abstract concepts, meaning as being mere necessities of thought or conveniences of language, are simply names without any true corresponding reality and that, in fact, only particular objects exist; there are, therefore, no universal essences whatsoever.

The nominalist contends, e. g., that one can see an individual man, a human being, but there can be no universal term that talks about man as an abstract category as if it possessed any reality. Thus, an individual person has a human nature qua real being; but, the universality of a human nature qua nature of humanity does not philosophically exist. There are, as other examples, individual dogs or cats; there is, however, no universal “thing” that can be specified as dog or cat. Words such as liberty, freedom, truth, beauty, justice, etc. are said to be mere abstractions qua semantic devices having no true substance whatsoever.

The inherent and integral and unavoidable contradictions and conundrums, involved in such a bold contention, get rudely pushed aside in the subjective-relativist rush toward upholding the nominalist asseveration, meaning totally regardless of the actuality of the matters discussed. Objectivity and subjectivity, among other basic noetic results, get necessarily reversed within the scope of human understanding and comprehension, not surprisingly. It is, in short, Occam’s Razor gone mad.

Thus, ultimately, it is the extremely anomalous positing that metaphysics can exist without any reference to a metaphysical order (as if a river could be composed without any water); a once truly radical or extremist point of view that, today, is held to be completely normal. It is, therefore, as to its logical consequences, a world seeking to be entirely bereft of God and, finally, of sanity itself in the cause of pursuing nominalism to its final epistemological conclusion.

One can see, as with, e. g., Communism, how an ersatz religion (or the oddity of a secularist religion) qua ideology can induce people to murder millions of their fellow human beings, though not ever thinking that such slaughter is clearly indicative of insanity. If this can be understood, however, then the true meaning, implications, and ramifications of modernity are then revealed.

Objective knowledge, unfortunately, becomes difficult to grasp whenever Occamism operates on the human brain. And, further, objectivity itself has its very existence questioned when this kind of “logic” gets worked upon over time; both philosophy and political philosophy, as consequences, have become progressively corrupted as the centuries have passed such that, for the vast majority of people, nominalism has simply become an unrecognized pandemic attitude and accepted orientation of thought within all of modern civilization.

But, there are continuing philosophical problems left unresolved. How can, in fact, the particularity of a particular being, said to be human, be then held to be possible or plausible without a prior paradigmatic conception of what it is that gets properly defined as human, especially a human nature? How could, by extension, someone be said to possess a human nature without there being the definition of a nature that is applicable, by definition, to a human being and, thus, to all human beings who have ever lived or, of course, are alive now?

The moderate realism approach of Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas, along with most of Platonic thought, gets weirdly turned upside down and inside out in the effort to create an Occamist worldview where there are no universals imaginable (read: permitted). There were, as to the reductionist mentality involved, many consequences, as could be guessed, in the field of intellectual or political-intellectual history.

For instance, the 18th century Enlightenment’s deification of Reason witnessed a modern form of (liberal) tyranny (or insanity) then known as enlightened despotism; this fitted in well, in turn, with Rousseau’s contention, e. g., that men had to be forced to be free, which logically originated, of course, the concept of democratic despotism as a means of (insane) progressive liberation, of creating the New Eden on earth, Utopianism. (The logical end results, in their turn, lead to both Nazi death camps and Communist gulags in the 20th century, for the road to Utopia always takes the path toward necessary dehumanization, due to the ideological rationalization of murder on a grand scale.)

By the early 19th century, Jeremy Bentham, the father of utilitarianism, could gratuitously, meaning just passingly, dismiss all of Natural Law as being only “Nonsense on Stilts” in his aggressive efforts at the totalist (insane) rationalization of human life, culture, law, civilization, and society. Modernity, thus, vigorously so spreads philosophical/metaphysical ignorance and, therefore, continuously incapacitates the human mind from reasoning correctly about fundamental matters concerning the human condition and the consequences of the thoughts and actions of fallen creatures living in a fallen world; sin itself gets ignored, of course; rationality qua right reason gets wrongly confused with Rationalism, a form of ideological insanity…

Thus, e. g., Martin Luther, educated primarily by nominalist-inspired teachers of theology, was then supplied with many currents of reasoning that conformed easily toward the creation of Protestantism, the truest theological expression of nominalism ever fashioned or conceived by mortal man: sola Scriptura and sola fide. Someone can actually think of himself as being a good Protestant who, in effect, constitutes his own church and acts as his own pope, in the spirit of individualism writ large.

The metaphysical order qua Supreme Being becomes flexible and adaptable to the variable and various (read: Protestant) belief needs or values of diverse kinds or types of Christians. From the Catholic point of view, however, it was obviously blasphemous to the nth degree for the so-called Reformers to, thus, reform God; Protestant converts to Catholicism get the point. But, one ought to be able to plainly see how Protestantism blends in quite well with the flow and logic of modernity.

The Protestant Revolt was and necessarily remains, therefore, the vainglorious and forever dubious theological effort at (supposedly) achieving the reformation of the Lord. This is easily proven empirically in how dozens of sects had expanded into, first, hundreds and now continuingly thousands upon thousands of sects that continue to multiply; the so-called Reformation is endless because God must be made to conform to the dictates of a multiplicity of divergent and disputational consciences, which process displays the forever inherent and integral irrationality of Protestantism, of course…

What is meant? All the ideologies of modernity, meaning inclusive of Conservatism, Communism, Nazism, Fascism, Liberalism, Anarchism, Libertarianism, Feminism, etc. can be then traced through many kinds of philosophical attitudes such as materialism, hedonism, secularism, humanism, subjectivism, pragmatism, positivism, nihilism, reductionism, etc. back to their root or fundamental cause: Nominalism.

Unsurprisingly, every heresy attacking Catholicism can be drawn, either directly or indirectly, to the same source or, rather, mental contagion; and, moreover, the desacralized and neopagan West, without a doubt, is now intellectually and morally disarmed in the face of an increasingly militant and aggressive Islam. In turn, postmodernism in thought (deconstructionism, etc.) would be inconceivable without a prior modernism in cognition; both modernism and postmodernism, as popularly understood, are ultimately traceable to the germinal nominalist point of view…

“At heart, Nominalism is an attempt to explain why we call a cat a cat. It’s not concerned with the etymology of the word “cat” but with why it is even possible to give a single name to all of these animals. The central claim of Nominalism is that only individual realities exist; there is only Fluffy and Garfield and Mittens, and each is completely singular and unique in its existence. Universals, like the word “cat,” are simply useful labels that we humans can apply to things that we perceive as being similar, but do not correspond to anything in reality. There is no such thing as cat nature that is really shared by each cat and gives a real basis for grouping them as a species. There is simply a name. Of course, this goes beyond felinology to all universals. Most troubling is that Nominalism claims there is no such thing as human nature, simply individual, unrelated human beings.

When considered from a theological perspective, Nominalism has a drastic effect on our relationship to God. Whatever order and structure we may observe in the world cannot be rooted in the real relationship between different types of things, because there are no types of things to relate.

Whatever order we find can only be rooted in God’s free choice. Thomists absolutely agree that God created and continues to maintain creation with absolute freedom, but they see the result of that freedom as an expression of God’s providential wisdom.

For the Nominalist, the majesty of the created order is not really a glimpse at God’s wisdom but simply of the way he wants things to be for the moment. In the moral order, if there is no such thing as human nature, there is no such thing as natural inclination towards happiness or natural law. There is no rational reason behind what makes a particular action good or bad; there is only God’s free choice.

William of Ockham, the founder of scholastic Nominalism, took this extreme Voluntarism, this overemphasis on God’s free will, so far as to claim, “God can command the created will to hate him,” and by that command, the hatred of God would be good. He saw this as possible not simply in this world. Rather, “just as hatred of God can be a good act in this world, so can it be in the next.”

Ockham never claimed that God had ever commanded this, and Ockham recognized a customary order in things. But he held on to the idea that there was no guarantee that this order would not completely change tomorrow.

As influential as Nominalism was in the 14th century and continues to be in various guises today, the phrase “anything can signify anything” isn’t really expressing medieval Nominalism. It is expressing a sort of New Nominalism* that we see in today’s culture, a sort of modern amalgamation of Nominalism and Voluntarism, but without even God as the ultimate arbiter.

There seems to be a growing trend that assumes not only that universals are merely names with no real significance, but even that the meaning of these names is entirely up to the free will of each individual. What it means to be a man or a woman is becoming something subjective and self-defined. Whether a slur is really a slur or a sign of affection is simply up to the one who uses it or who hears it.

Further, this personal Voluntarism ensures that no one need be bound by their past opinions on a word from one moment to the next. What was once, in the moment, a life-long vow “for better or for worse” might eventually become simply a nice turn of phrase, said on a day long ago but that never really meant anything…

While Nominalism tended to cut us off from God’s wisdom and the well-ordered plan of salvation, the New Nominalism introduces a sort of man-made Babel, cutting us off from one another and even from our very selves.

When words, including universals, lose their connection to an objective reality, we lose the ability to speak honestly about truth and goodness. While it may be true on some abstract level that “anything can signify anything,” only certain things actually signify the truth, only certain statements actually correspond to the reality they are conveying. Without trust in the reality underlying our words, the truth about ourselves and about God will always escape us, no matter how hard we will otherwise.”

Love,

Matthew