Please click on the image for greater detail

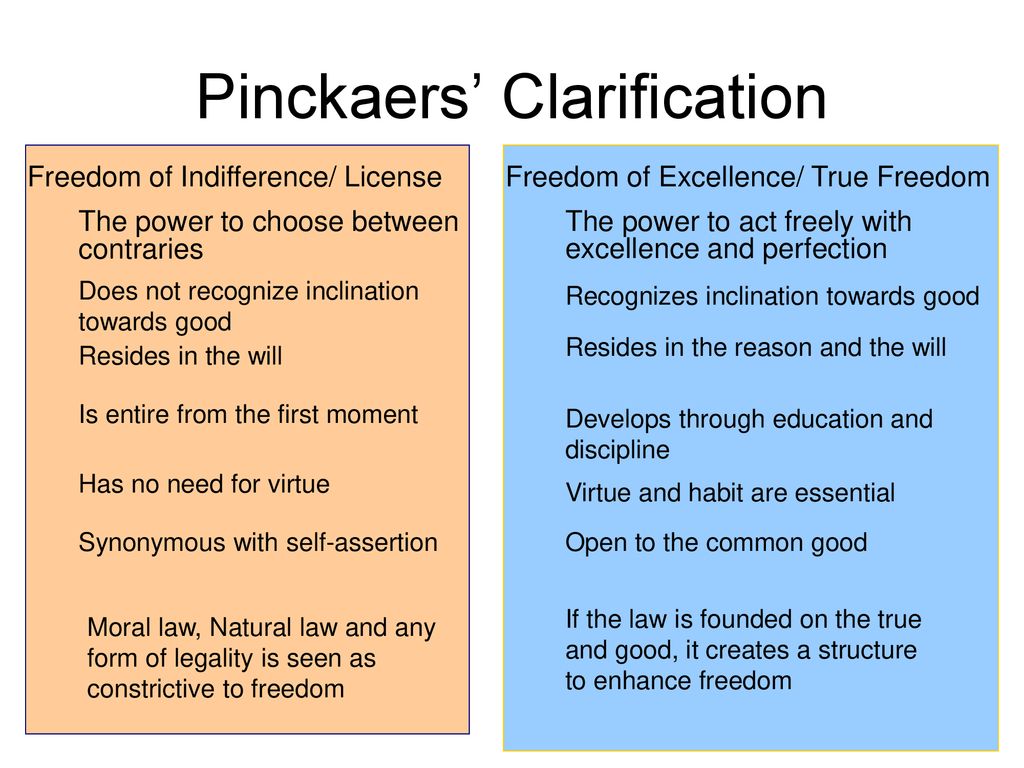

Thomas Aquinas‘s use of the terms libero, libertas, and liberum arbitrium in the Summa theologiae gives us a wealth of information about free will and freedom. Human beings have free will and are masters of themselves through their free will. Free will can be impeded by obstacles or ignorance but naturally moves toward God. According to Servais Pinckaers, our freedom can be that of indifference (the morality of obligation) or that of excellence (the morality of happiness). The difference is that of free will moving reason versus reason moving free will. The freedom of indifference is the power to choose between good and evil. The will is inclined toward neither and freely chooses between them. The freedom for excellence is the power to be the best human being we can be. Here the rules, or what makes for a good human being, are the grounding for freedom. One who observes these rules has the freedom to become excellent. According to Aquinas, intellect and will have command over free will. This then is true freedom, and on this Aquinas and Pinckaers agree. We do not have freedom of indifference, we have freedom for excellence. Anything else makes us slaves.

-by Dr Kenneth J. Howell, a former Presbyterian converted to Catholicism. Dr. Howell holds a Ph.D. in Linguistics from Indiana University and a Ph.D. in the History of Christianity and Science from the University of Lancaster (U.K.). A Presbyterian minister for eighteen years and a theological professor for seven years in a Protestant seminary, Dr. Howell was confirmed and received into the Catholic Church in 1996. He and his wife, Sharon, have three children. They live in Champaign, Illinois.

“To many outside—and some within—the Catholic Church, it seems an oppressive institution. With its long list of dos and don’ts, the moral positions of the Church are seen as stifling. Against the background of an increasingly libertine American culture, Catholicism seems to be a throwback to the oppression of the Crusades and the Inquisition. The Church may no longer resort to threats of torture, but its moral strictures are torture enough for a populace used to freedom and liberty.

This perception of the Church contrasts sharply with the perceptions of practicing Catholics who have found freedom and liberation in the moral certitudes of the Church. When the moral positions of the Church are combined with its spiritual emphases, the faithful have often seen the Church as a haven for true happiness. The reason for these different evaluations of the Church has to do with two different views of freedom.

Why do those outside the Church see it as an oppressive institution stuck in the past, unable to change with the times? One reason is surely that outsiders believe in the freedom of indifference, whereas the Church espouses a freedom for excellence. Freedom of indifference is the notion that every person should have the unencumbered liberty to do whatever he wants unless it hurts someone else or infringes on someone else’s freedom.

In its current popular form, the freedom of indifference found classic expression in the views of nineteenth-century philosopher John Stuart Mill. Mill’s On Liberty (1859) enunciated a view that was free of metaphysical or natural grounding. The individual stands front and center in Mill’s philosophy. Governmental power cannot be used to compel people to certain beliefs, nor can prevailing public opinion be allowed to squelch individual views. The only legitimate restriction on an individual’s liberty is when he becomes a threat to others. So society may rightly limit a person’s freedom if that freedom poses harm to others. Barring that danger, Mill insisted that “over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”

Mill’s sovereignty of the individual extended even to the possibility of self-destruction. Even if the individual wishes to harm himself, society has no justification for intervention. Society should be indifferent in the face of the individual’s choices. This latter case illustrates how far Mill and his intellectual heirs are from any sense of natural rights or metaphysical grounding. Whether self-harm (e.g., by drug use) or even suicide is morally justified is not a concern of anyone but the individual.

Mill’s views, which surely were not his alone, have filtered down to the common culture of the Western world. The advocacy of abortion, physician-assisted suicide, and sexual orientation are all instances of Mill’s individualism. But there are smaller ways in which freedom of indifference is expressed in current culture. Since there is an inherent relativism and subjectivism in this view, it manifests itself aesthetically in the bromide that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. No such thing as inherent beauty exists.

Such relativist aesthetics has found its way into academia. Humanists gladly affirm that there is no good or bad literature, painting, or music. All is personal preference. In the moral sphere, no sexual arrangement is wrong if done by mutual consent. Even things once considered natural are now relegated to the category “social construction.”

Gender, once thought to be rooted in the natural makeup of the male and female sexes, has now been reclassified as a social construction, not a natural reality. Benighted psychiatrists once treated gender identity disorders as a therapeutic problem. Now the answer is surgical: “sex change” operations.

On what grounds is it argued that such operations are justified? The freedom of indifference. As long as such procedures leave others unharmed, no one has the right to tell someone what gender he is, regardless of his sex.

It doesn’t take much intelligence or hard thinking to live by freedom of indifference because of the radical individualism that underlies it. The only relevant factor is the choices and preferences of the individual.

In a statement that baffles the intellect, the U.S. Supreme Court weighed in with its 1992 majority opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey by declaring, “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” Gone was any responsibility of the individual to examine reality, weigh arguments, and decide between competing moral frameworks. All that matters is the preferences of the individual.

Those who believe in the freedom of indifference will naturally see Catholic morality as an imposition tantamount to slavery. For those who believe that the individual is the agent and criterion of all moral judgments, public morality can at best be only a kind of social contract. And that contract ought to be minimal, reserving as much space for individual preferences as possible. In this view, Catholicism’s rich, detailed articulation of moral choices is a groundless imposition of the morality of a few upon a populace.

The Church agrees with the advocates of the freedom of indifference that individuals have to be free to make their own choices. However, utilitarians in the spirit of Mill tend to confuse the agents of moral decision-making with the question of criteria. The decades-old slogan that abortion is a woman’s choice confuses the agent with the criterion. No one doubts that it is a woman’s choice to have or not to have an abortion. That fact, however, says nothing about whether her decision is right or wrong.

Individuals must be free to make moral decisions, but this does not tell us what decisions will foster human freedom. Mill’s idea of freedom may protect an individual from society’s imposition, but it does not protect that person from the slavery of self-abuse. The reason is partly in the failure of utilitarianism to offer any account of virtue or how an individual develops in it over a lifetime. Utilitarianism and most modern forms of morality focus on moral decisions, not on human development in moral rectitude.

The ancients in general, and the Church in particular, saw that true human freedom is found not in moral indifferentism, but in a freedom for excellence. This is an interior freedom, an ability to govern oneself so as not to have to be governed from the outside. It is freedom in the form of self-mastery. The great difference between these two ideas of freedom can be pithily stated in an Augustinian fashion: “I sought happiness in freedom only to find freedom in happiness” (Quaesivi beatitudinem in libertate et non inveni libertatem nisi in beatitudine).

If we seek to be happy or blessed by the pursuit of freedom based on individual determination of right and wrong, then we only have to determine what will give pleasure. Of course, this theory fails to specify what happiness is or how it can be achieved other than self-determined pleasure. It requires little or no moral determination.

By contrast, freedom for excellence seeks to know the true nature of happiness (beatitudo) and to distinguish it from passing pleasure or self-destructive choices. The individual can study and reflect upon human experience to learn from those who have found true happiness. Upon finding it, that person can experience liberation from the need to seek happiness in destructive ways.

The difference between these two ideas of freedom can be seen most vividly with individuals in extremis. Under the influence of the freedom of indifference, it is almost impossible to believe that an individual might find happiness in a Nazi concentration camp or a Soviet prison. However, an individual who lives under the influence of the freedom for excellence can achieve a sense of interior freedom even while being severely restricted in movement and subject to inhumane conditions. Such possibilities are not pious platitudes. They are documented in the twentieth century.

Victor Frankel was a Jewish psychiatrist who was imprisoned in the concentration camp at Auschwitz and later at Dachau in World War II. He was, like his fellow prisoners, subjected to the most inhumane conditions imaginable. After the war, Frankel wrote a memoir that stunned the world. In Man’s Search for Meaning (1959), Frankel details how he found a sense of freedom in love. He noticed a difference between prisoners who possessed a rich interior life and those who did not: “Sensitive people who were used to a rich intellectual life may have suffered much pain (they were often of a delicate constitution) but the damage to their inner selves was less. They were able to retreat from their terrible surroundings to a life of inner riches and spiritual freedom” (p. 36).

Perhaps Frankel’s greatest discovery was that these “inner riches and spiritual freedom” were linked to love. In a passage where Frankel recounts his thoughts of his wife, he writes,

A thought transfixed me: For the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth—that love is the ultimate and highest goal to which a man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love (37).

Victor Frankel discovered that his happiness did not lie in freedom from restraint, but that his freedom resided in his inner happiness.

Walter Ciszek, the American Jesuit imprisoned in Siberia under the Russian Soviet regime, had a similar experience. There is no better way to understand his progress toward freedom than in his own words:

Across that threshold I had been afraid to cross, things suddenly seemed so very simple. There was but a single vision, God, who was all in all; there was but one will that directed all things, God’s will. I had only to see it, to discern it in every circumstance in which I found myself, and let myself be ruled by it. God is in all things, sustains all things, directs all things. Nothing could separate me from Him, because He was in all things. No danger could threaten me, no fear could shake me, except the fear of losing sight of Him. The future, hidden as it was, was hidden in His will and therefore acceptable to me no matter what it might bring. The past, with all its failures, was not forgotten; it remained to remind me of the weakness of human nature and the folly of putting any faith in self. But it no longer depressed me. I looked no longer to self to guide me, relied on it no longer in any way, so it could not again fail me. By renouncing all control of my life and future destiny, I was relieved as a consequence of all responsibility. I was freed thereby from anxiety and worry, from every tension, and could float serenely upon the tide of God’s sustaining providence in perfect peace of soul (He Leadeth Me, 79-80).

Ciszek offers a theological dimension missing in Frankel’s account, but both testify to the superior idea of interior freedom where no human cruelty can reach. On Mill’s account of freedom, there simply could be no possibility of happiness because Frankel and Ciszek lacked social freedom. Yet, by their accounts, these two men, one a Jew, the other a Catholic, found freedom in the inner contentment of seeing the beauty resident in their inhuman conditions.

Happiness is not found in liberty—that is, in the freedom to do as pleasure dictates—but liberty is found in happiness. Or, as the ancient Romans and early Christians called it, blessedness (beatitudo).

Love & truth,

Matthew