In the centuries after Christianity came to Ireland, Roman Catholicism thrived there. In the Dark Ages it was monks from Ireland, “the island of saints and scholars,” studying in Ireland and then moving out around Europe that helped preserve European civilization. But from the time that Henry VIII broke with the Church in the 1530s until the present day, all that changed and Ireland became a place of conflict.

Some of the first casualties of that conflict were the leaders of the Catholic Church in Ireland. Between 1534 and 1714, 260 Catholic clergy and laity were martyred in Ireland. One of those was Father William Tirry. William was born in Cork City in 1608 to a very prominent family. Twenty members of his family had been mayors of Cork through the years and his uncle was Bishop of the Diocese of Cork-Cloyne. The Tirrys were what was known as “old English,” those who had come after the Norman-English, but by the time William was born had been in Ireland for hundreds of years. Though they were loyal to the English crown, they were also staunch Catholics. William was a studious lad and, as was often the case in those days in prominent Catholic families, he was steered toward the priesthood. Though he spoke English and also learned Latin, Irish was his first language, another factor that would have enhanced his identification with Irish culture.

At the age of 18 William was accepted to study in the Augustinian order as a postulant at Cork’s “Red Abbey.” He later went to the continent, where he studied philosophy in the famous Augustinian house of study in Valladolid, Spain, where he was also ordained between 1634 and 1636. He then taught theology at the Augustinian College in Paris. He may have been back in Ireland by 1638. It was a fateful time in Irish history, as the Rising of 1641 was to begin shortly. Father Tirry was secretary for his uncle, the bishop, for a time. After the rebellion began, Cork was the headquarters of the Protestants of Munster province and remained relatively calm for a few years. Father Tirry was tutor to the children of two of his cousins during this time, the Sarsfields and Everards. The Everards lived in Fethard, County Tipperary, and would be very important to Father Tirry in the final years of his life.

In 1644, the ongoing conflict in Ireland finally disrupted Father Tirry’s life in Cork City, as the Catholic clergy was forced to flee. Father Tirry took refuge in the Augustinian friary in Fethard. He had several fairly peaceful years there, becoming the assistant to Father Denis O’Driscoll in 1646. They were able to minister to the local Catholics in relative peace for a few years, but the specter of Cromwell was on the horizon.

In June 1649 Father Tirry was appointed the prior of the Augustinian house in Skreen, County Meath. But Cromwell landed August 15th and occupied that area. It’s likely that Father Tirry either never took up that post, or had to flee it shortly afterwards, as he was still in Fethard in 1650. Father Peter Taaffe, who was appointed prior in Drogheda at the same time, died in the massacre by Cromwell’s troops there.

In the spring of 1650, Cromwell’s army arrived in Fethard and all the Augustinians had to scatter to the countryside and go into hiding. Father O’Driscoll and Father Tirry remained on the run in hiding in the area for the next four years, while ministering to the Catholics of the town. Father Tirry was said to have sometimes moved about disguised as a soldier and for much of the time was often hidden in the home or on the property of his former employers, the Everards. Many people in town knew the Everard family was hiding him, but for several years none betrayed him.

On January 6, 1653, the English parliament declared any Roman Catholic priest found to be ministering to a congregation in Ireland to be guilty of treason. Some priests fled to the continent, but many did not, including Father Tirry. Those who stayed had a bounty put on their heads and priest hunters roamed the countryside. It was a time of great suffering in Ireland, when famines were common and many were desperate and starving. Eventually he was betrayed by three local people, who each received 5£s.

On Holy Saturday, March 25, 1654, English soldiers broke into Father Tirry’s hiding place at the Everard property and arrested him. He was in his vestments preparing to celebrate a Mass somewhere and they also found papers in which he defended the Catholic faith. This was irrefutable evidence against him.

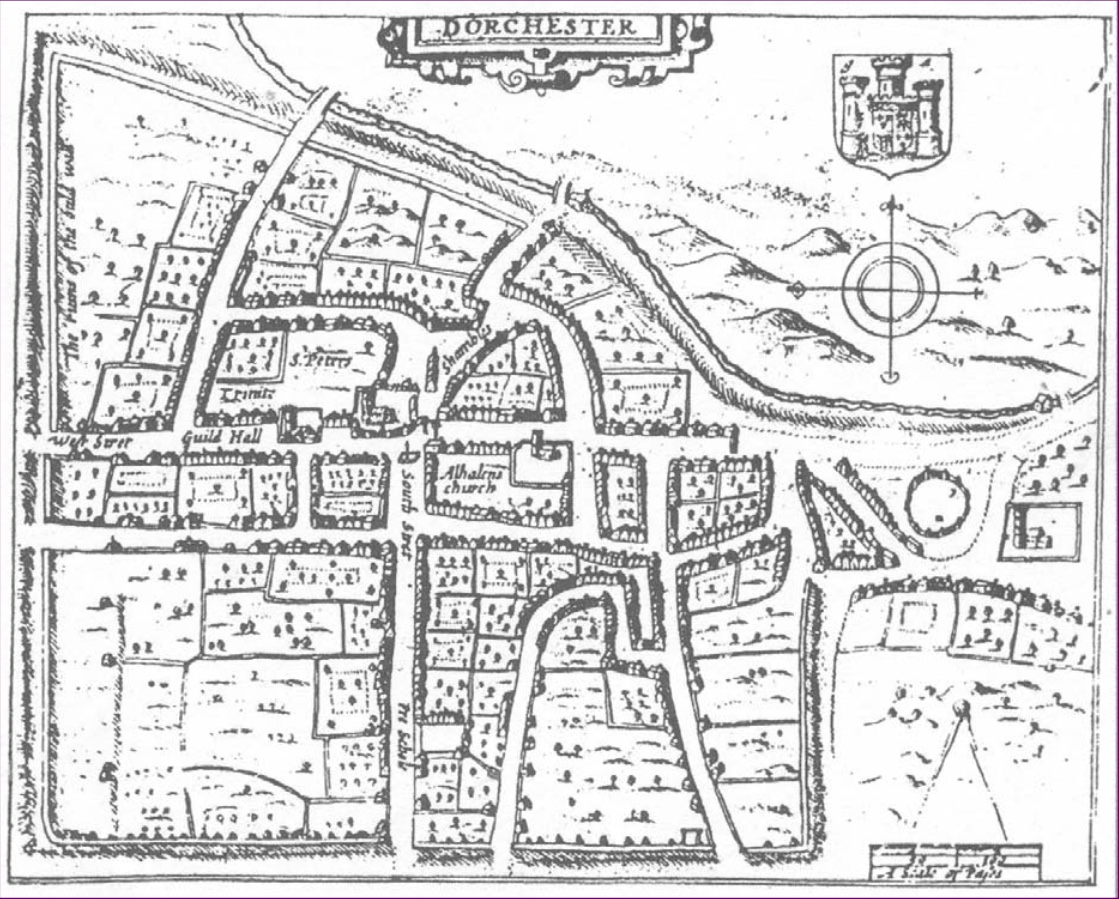

-part of the old city and town walls of Fethard, Ireland

Ordinarily this would have resulted in Mrs. Everard (a widow) being arrested and probably executed for aiding a priest, but the family must have been well connected and she was not harmed. Father Tirry was transported to Clonmel Gaol. Not every clergyman who was caught at the time was executed — some were deported. There were several other held in the gaol with Father Tirry then who were banished rather than being executed, including Fathers Walter Conway and Matthew Fogarty, who would provide much of the extant information of Father Tirry’s imprisonment and execution. Fathers Conway and Fogarty reported that Father Tirry immediately improved the morale of the prisoners with his piety and positive attitude.

His efforts ministering to the local population over the preceding decade must have left a strong impression on them, for Conway and Fogarty reported that when the Catholics in the area heard that Father Tirry was in the gaol, crowds of them came there to see him. Marshal Richard Rouse, who ran the gaol, apparently admired Father Tirry as well, as he went out of his way to see to his comforts and allowed some of his many visitors to see him.

As with nearly all trials of Irishmen at that time and for nearly three more centuries to come, the assigned jurors were those the government trusted to return the “correct” verdict. This jury included a Cromwellian commissioner and an army colonel who would no doubt keep the other jurors in line. And in the case of Father Tirry, it’s likely that his high standing with the local Catholic population worked against him with regard to banishment versus execution, as did the writings that found when he was arrested, which were highly critical of the Protestant church of Ireland. If he knew that, it did not cause him to waver in his faith.

At his trial, when pressed to bend to the government’s authority, he replied that, “in temporal matters I acknowledge no higher power in the kingdom of Ireland than yours, but in spiritual affairs wherein my soul is concerned, I acknowledge the Pope of Rome and my own superiors to have greater power over me than you others.” He must have known such a pronouncement would make them believe that even if exiled he would return again, ensuring his death, but his faith was stronger than his fear of death.

Both Fathers Tirry and Fogarty, who were tried together, were sentenced to death, but in Fogarty’s case the sentence was commuted to banishment. Marshal Rouse allowed Father Tirry to be held in a house he owned after his trial, so people could easily came and visit him while awaiting word of when his sentence would be carried out. In a last act of kindness to his flock, Father Tirry had 46 loaves of bread given to the poor to atone for the sins of his 46 years of life. On May 11th, he was informed he would die the following day, and replied in his native Irish, “God Almighty be thanked Who chose me for this happy end.”

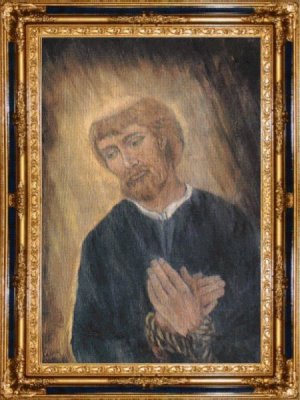

On the morning of the 12th, Marshal Rouse arrived to take Father Tirry to be hung. After having his hands manacled, he knelt in the door and got a final blessing from his fellow priests, whose affection for him must have created a most poignant scene. The procession to the gallows was guarded by English soldiers, as well it needed to be, as the streets thronged with people coming to see their beloved priest for the last time. Many were said to be weeping and some grabbed the hem of his garment and kissed it, receiving his blessing. He walked holding a set of beads, reciting the rosary as he went to the market square of Clonmel.

Reaching the gallows, Father Tirry was allowed by Rouse to address the crowd, much to the displeasure of a Protestant reverend who implored Rouse to “get on with it” in the middle of the father’s gallows speech. But Rouse’s kindness to Father Tirry would continue. The crowd now was turning angry at what was about to happen and pressing in toward the soldiers surrounding the gallows, but Father Tirry implored them to stay calm and allow him to “go in peace.”

“I would have life and favor if I defected to you,” Father Tirry told the reverend, “but, I prefer to die for the true religion.” And, in his final comments, he showed how deep his devotion to that religion was, when he forgave the three residents of Fethard who had betrayed his location to the English, and prayed for their salvation. He also asked any priest who might be in disguise in the crowd, as they would have to be, to offer him absolution. His old friend Father O’Driscoll was, indeed, there and surreptitiously gave it. O’Driscoll was still on the run and would never be captured, but his health would be broken by that exhausting life and he would be dead the following year.

Father Tirry then signaled to Rouse, who had assured him he would not give the command to push him from the ladder on which he was standing until he was ready, that he was prepared for the end. The deed was done and the crowded gasped as the good Father’s neck snapped and his lifeless body hung before them. It was said that none who witnessed it, Catholic or Protestant, failed to be admire the strength and courage with which Father Tirry had faced his final moments on earth.

-ruins of Fethard Abbey, Ireland

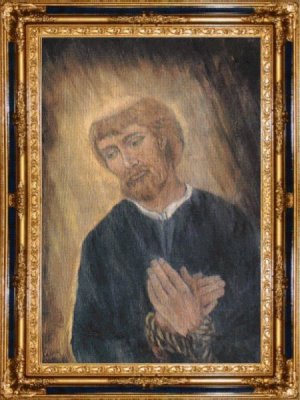

The mayor of Fethard was allowed to bring Father Tirry’s body back there. He was buried in the grounds of the Abbey in Fethard, though its exact location is lost to us. His sacrifice for his faith was not forgotten by the people of Ireland, however. In 1919, Father Tirry was one of 260 Irish martyrs whose names were submitted to Rome for sainthood. On September 27, 1992, 17 Irish martyrs were beatified by Pope John Paul II, and on that list was William Tirry, now one step away from being a saint.

Loving Father, we praise you for the seal of holiness your Church placed on Blessed William Tirry of Fethard, who willingly gave his life for your Gospel truth which he professed and lived. Grant through his intercession an answer to our prayers now in our time of need. We pray especially for………………… May your holy will be done. We trust in your mercy, and pray too that in your blessed providence, the name Blessed William will soon be added to the list of our saints.

We make our prayer through Christ our Lord.

Love,

Matthew